Rotary dial telephones, Morse code equipment, old radios – the history of electrical engineering can be found in the basement of the faculty of EEMCS.

Kees Wissenburgh (78) estimates that he’s had twenty-five thousand tubes in his hands. For the last five years or so, he has managed the storage area for these old electrical components: tubes for radios, radar and TVs.

“This collection was started by a TU Delft staff member who had worked as a radio operator. He had been to sea and had connections everywhere”, explains the former analogue electronics lecturer. The room is filled to the ceiling with hundreds of boxes. “What’s in those boxes is often a surprise.”

‘This tube comes from a German V2 rocket, it’s a unique item’

One of the tubes has an eagle and a swastika drawn on it. “This comes from a German V2 rocket”, says Wissenburgh. “It’s a unique item. V2 rockets were fired to England from The Hague and other locations. I still vividly remember the sound they made. It resembled that of the jet engine of a modern aeroplane. Clutching my teddy bear, I would sit in the stairwell listening. If the sound suddenly stopped, you knew that the rocket had crashed. One came down just around the corner from my aunt’s house.”

“I built my first radio with tubes as a young boy. They’re back in fashion now. They’re ‘retro’. Some people say that the sound of a tube amplifier is warmer than that of a transistor amplifier. I don’t believe a word of it. It makes no difference for sound reproduction. Sure, if you want to distort the sound of an electric guitar a tube amplifier sounds better. It provides nicer overtones.”

Kees Wissenburgh:”Some people say that the sound of a tube amplifier is warmer than that of a transistor amplifier. I don’t believe a word of it.”

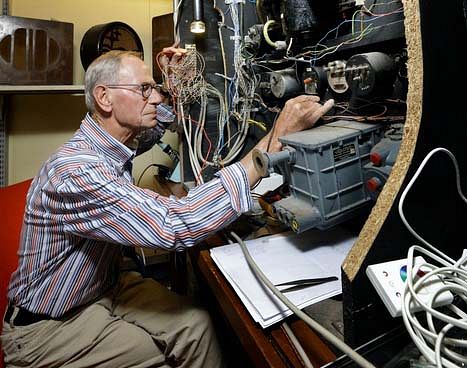

Kees Wissenburgh:”Some people say that the sound of a tube amplifier is warmer than that of a transistor amplifier. I don’t believe a word of it.”Jan Meijers (72) and Frans van Zuijlen (70) are repairing a load resistor. “With a device like this we can test generators that generate 380 volts”, explains Meijers. “The load resistor had to be disassembled because it contained asbestos. This device is from the high-voltage laboratory. Is this heritage?”(laughing) “Everything involving power current is slowly but surely becoming heritage.”

Bolt fanatics and sparkies

Meijers is a precision mechanics man, and has been since his military service. He worked on flight instruments at Twente air base. “They call me a bolt fanatic here. And we call those who work with electronics ‘sparkies’.”

“Tinkering is fun. You can’t just throw old things away can you? It’s important for the students that we save all this equipment. While students need to work in the new computer age, they also need to know where we come from.”

Rob Timmermans: “Pendulum clocks were highly accurate and often hidden away in basements deep underground, away from vibrations and pressure and temperature fluctuations.” (Foto: Sam Rentmeester)

Rob Timmermans: “Pendulum clocks were highly accurate and often hidden away in basements deep underground, away from vibrations and pressure and temperature fluctuations.” (Foto: Sam Rentmeester)“I’m fascinated by masters”, says Rob Timmermans (70). “I try to rescue as many as I can from old buildings. Slaves don’t interest me as much.”

Mad about masters

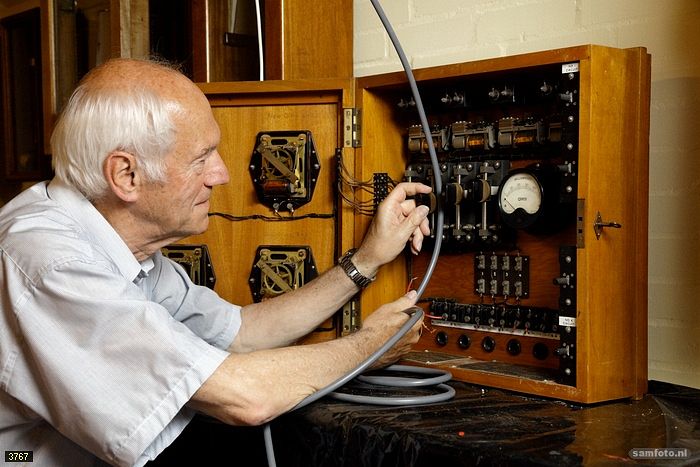

Timmermans enjoys playing with jargon. What he’s really talking about are master clocks. Long before we used GPS to set our clocks, we used these pendulum clocks for this purpose. They were highly accurate and often hidden away in basements deep underground, away from vibrations and pressure and temperature fluctuations. These clocks sent the time to dozens of other clocks – slave clocks – to ensure that they all ran in sync.

“The development of these clocks really took off a century ago”, says Timmermans. “All over Europe, the railways started to run on schedule. The time had to be the same at every station. This system also became commonplace in big office buildings.”

‘The time had to be the same at every station’

Often a master clock alone wasn’t strong enough to control all the slave clocks. The signal was then sent to an amplifier first. Timmermans is working on such an amplifier now. He is preparing for an upcoming exhibition called Op tijd schakelen (‘Switch on time’).

“I spent forty years in telecommunications, for Siemens, Alcatel, KPN and other companies. I launched numerous initiatives to preserve heritage. I founded the Dutch Telecommunications Heritage Foundation (Stichting Telecommunicatie Erfgoed Nederland). But this, the master clocks, is something I do privately. It’s a passion.”

Peter Stiefelhagen: “This is good stuff. These radio beacons enabled the pilots to determine their position.”

Peter Stiefelhagen: “This is good stuff. These radio beacons enabled the pilots to determine their position.”Peter Stiefelhagen (77) can be found in the basement every Monday. He’s been coming here for ten years now. He is busy mounting a World War II radio bacon monitor on a panel containing instruments from allied bombers. “This is good stuff. These radio beacons enabled the pilots to determine their position.”

‘All of these devices come from aeroplanes that crashed’

On-board compass, temperature gauge, exhaust temperature gauge – the engineer has already installed dozens of instruments and linked them to a panel with named buttons. Press a button and you’ll see a red light illuminate next to the instrument concerned. “All of these devices come from aeroplanes that crashed or were destined to be scrapped.”

Jack-of-all-trades

Stiefelhagen is a jack-of-all-trades in the basement, working on different projects. Before focusing on flight instruments, he restored a gyrocompass that had stood outside on the deck of a big ship.

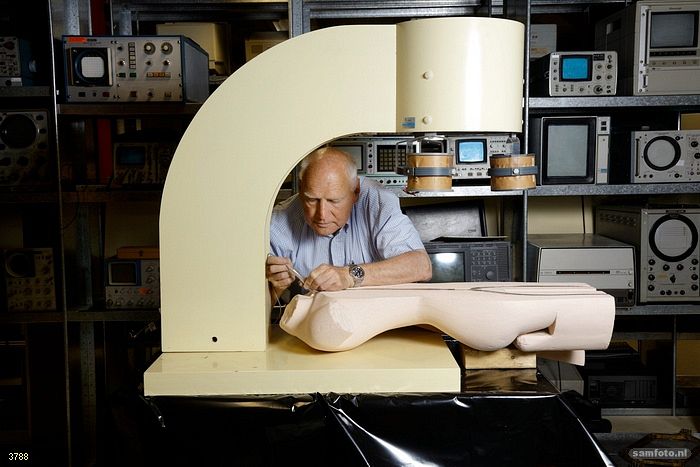

Piet Trimp: “A student used this doll to refine a technique for guiding catheters through a patient’s bloodstream .”

Piet Trimp: “A student used this doll to refine a technique for guiding catheters through a patient’s bloodstream .”“There’s a story connected to this doll”, says Piet Trimp (68). “I worked on this fifteen years ago for the electronic instrumentation research group. A student used this doll to refine a technique for guiding catheters through a patient’s bloodstream when placing a stent. What was different about this was that the catheter had magnetic sensors, enabling the physician to see where the catheter is in the bloodstream. That means that he didn’t have to make new X-rays all the time.”

Circulatory system of garden hoses

“The doll is made of polystyrene and came from a shop display”, continues Trimp, who started working in the basement when he retired three years ago. “I cut it through lengthwise and used garden hoses to model a circulatory system on the inside. This doll is genuine TU Delft heritage.”

Comments are closed.