Science is not above sexism. At least scientists and engineers are not. In June, Nobel Laureate Tim Hunt made sexist remarks about women being too distracting for laboratories.

A social media backlash ensued.

‘#DistractinglySexy’ became a hot Twitter topic, with female engineers posting photos of themselves at work – in clean suits, hard hats or simply knee-deep in research.

In July, ‘#LookLikeAnEngineer’ went viral after Isis Wenger, a software engineer in the US, was told she was ’too pretty’ to be an engineer. A number of female scientists from Europe added their voices to both movements, highlighting the fact that women in science continue to face explicit and implicit biases every day. We spoke to organisations across Europe and researchers at TU Delft to get a picture of the situation.

According to European Commission report She Figures 2012, the average proportion of female researchers in the EU-27 stood at 33% in 2009. Germany and the Netherlands have only 25% and 26% female researchers respectively, whereas Bulgaria, Portugal, Romania, Estonia, Slovakia and Poland have at least 40% female researchers. While the European target is 25%, the number of female professors in the Netherlands is only 15.7%. National organisation Dutch Women in Science (LNVH) found that it will take about half a century for the male and female ratio to even out in technical fields in the Netherlands.

“The pattern of male dominance is still visible. Only one out of six professors is female. We fare better than a lot of countries, but when compared to some Scandinavian countries, or even the US, we have a long way to go,” said Marike Bontenbal of UNESCO Netherlands. Together with L’Oreal, UNESCO offers an annual fellowship to women in science in several countries. Started elsewhere in 1998, it was only introduced in the Netherlands in 2012.

Today, there are number of other national initiatives. The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research even co-organises an annual event with LNVH called Pump up Your Career. It focuses on talent and career development for women in science.

Unconscious bias

The European Platform of Women Scientists, which has members from across the continent, is taking up the issue at Ready for Dialogue, an upcoming conference in Germany in November. “There is still unconscious bias against women and subtle sexism that are hard to fight. The mental image of a scientist is very much that of a serious looking bearded white man.

From subtle discrimination to open harassment, there is still a lot that needs to change,” said Tatjana Parac-Vogt, president of Belgian Women in Science (BeWise) Association and professor of chemistry at KU Leuven.

“Belgium has initiatives such as Ladies in

Science and Green light for Girls designed to encourage young girls to opt for science,” she said. The United Kingdom began addressing the imbalance sometime back according to Hayley Hung, TU Delft Assistant Professor, who studied electrical engineering at London’s Imperial College between 1998 and 2002. She was one of the only 10% of females. “One professor would say ‘Good morning, lady and gentlemen’ in the tutorials I attended!”

“In many ways science is a much more traditional space and still associated with male figures. This is compounded by issues of work and life balance,” explained Bontenbal. Not only does this mind set discourage female students from opting for science, it is found to have an impact on selection committees when selecting candidates as well.

“A gender-mixed composition of nominating commissions, an increase in the objectivity of the applied selection criteria, tutoring of women, or even the fixing of quotas, are all policies that are generally evoked…to balance out the unequal situation that continues to prevail in the academic sector,” notes She Figures 2012. The report adds that “there is not just a glass ceiling, but a ‘maternal wall’ is hindering the career of female researchers.” Research shows that while at a BSc and MSc level the gender balance is lot more even, it starts to skew when women are in their late 20s and 30s. At TU Delft there are only 26% female PhD candidates as compared to 32% BSc students and 50% MSc students. Interestingly, in the Faculty of Architecture and the Faculty of Industrial Design women comprise 56% and 59% of BSc students respectively. Some teams now actively look for female candidates while initiatives such as the Delft Technology Fellowship continue to boost the numbers in other areas.

Jinrui Zhang is happy to have a better work life balance in the Netherlands than in China

Jinrui Zhang

Cell Systems Engineering Researcher, Faculty of Applied Sciences

Zhang did her PhD in chemistry and molecular biology at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in China. She feels TU Delft provides her with a quality research environment where state of the art techniques are applied to practical problems. While the full professors are predominantly male, Zhang feels there’s a 50% ratio between PhDs and post-docs and lab technicians.

Inspiring change: Still in touch with her university in China, Zhang is happy to provide information to those in her field seeking to go abroad. Zhang has participated in workshops that call out male bias and make women scientists more aware of it. Key issues: She believes that women are more guarded as they strive for perfection, but this is misinterpreted as a lack of ability. Having a 5-year-old daughter, work-life balance is an important factor for her. “In the Netherlands it’s possible to have a good balance. There are many holidays and you can work part time. There is a good childcare and healthcare system.”

International experience: In China, she felt the male-to-female ratio of students was around 40-50% but only 20% among faculty. Top ranking female scientists were rare. “It’s good to see rising awareness of gender issues in China. Women should have more opportunities.”

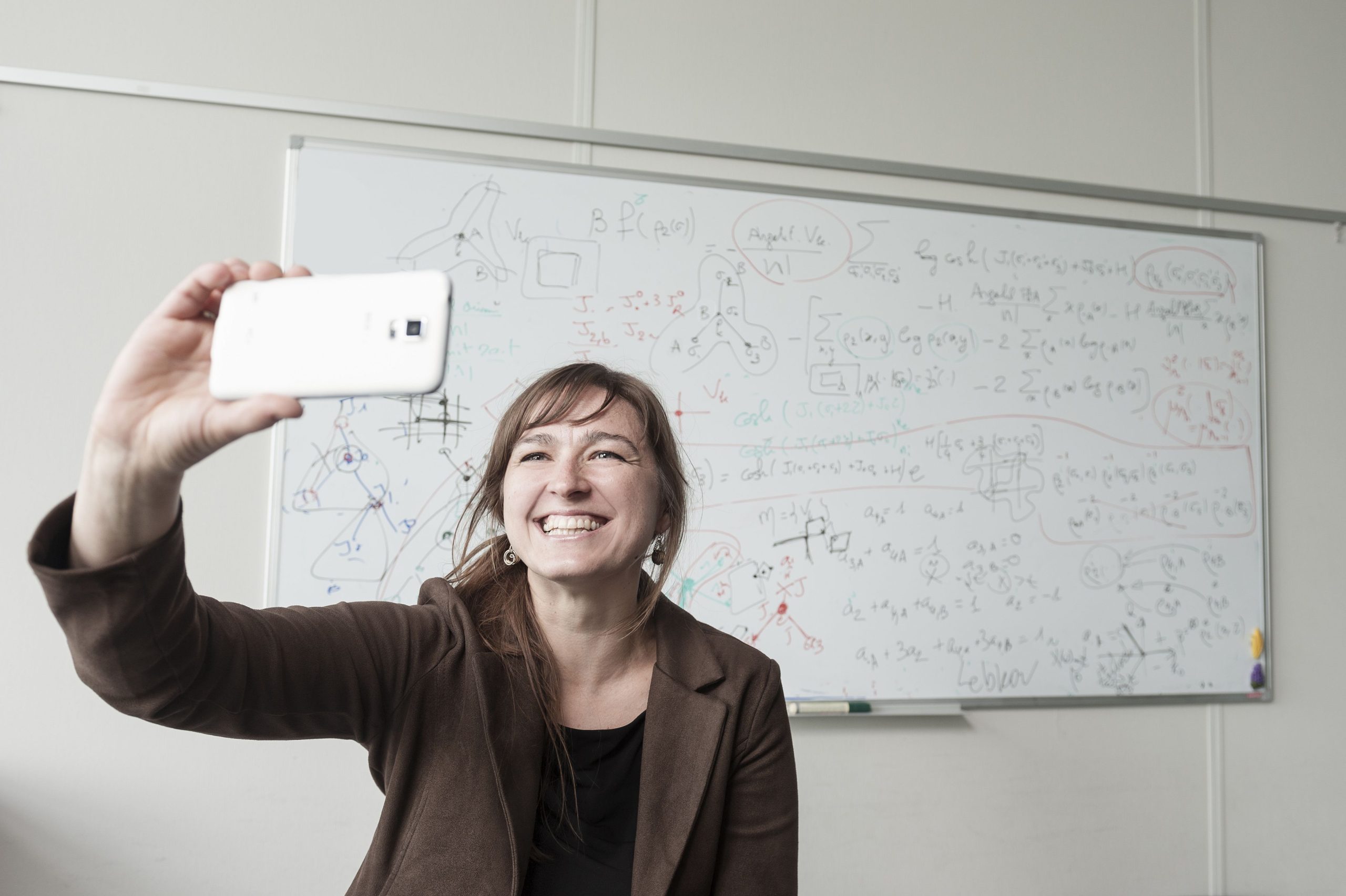

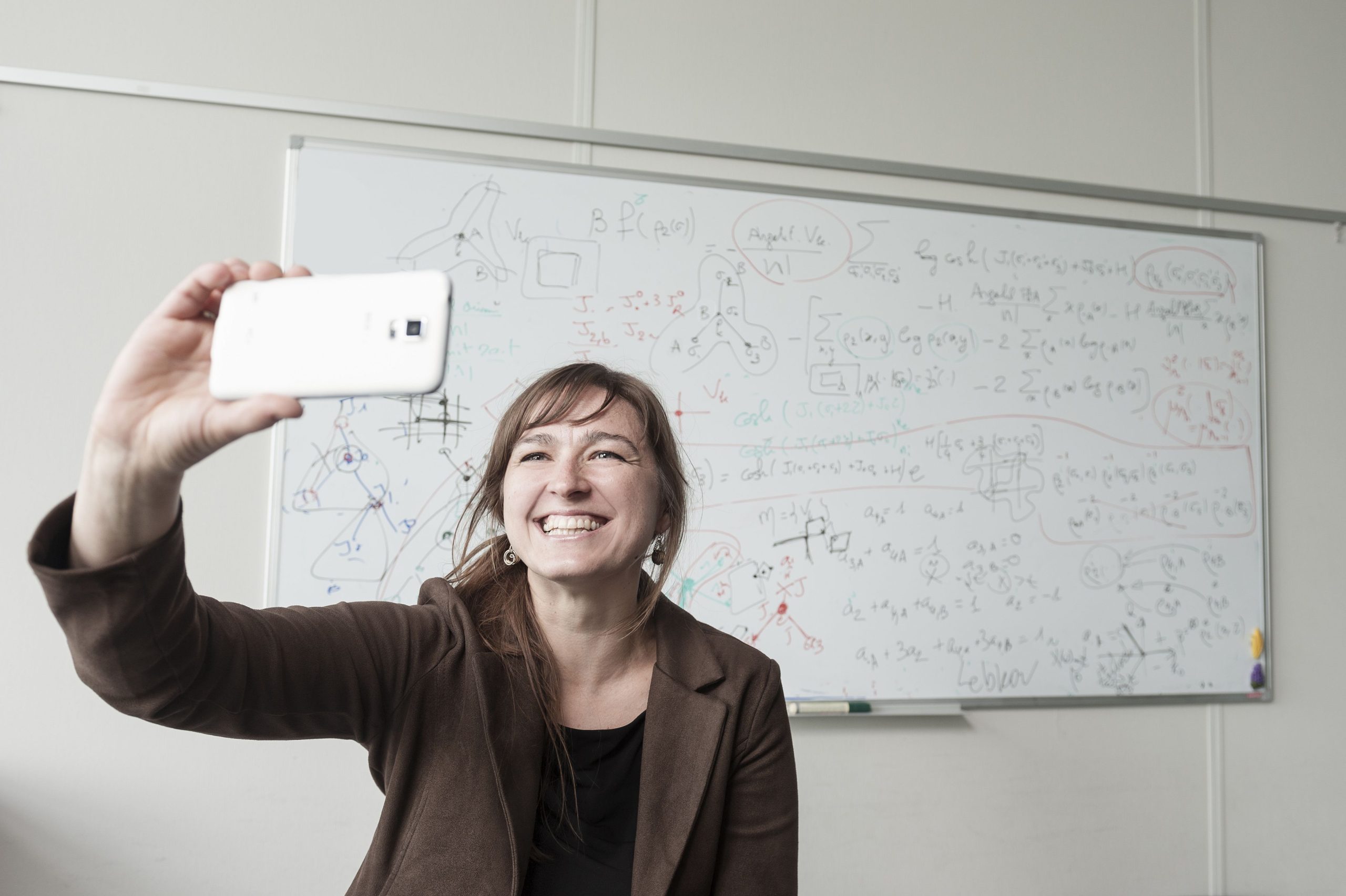

Wioletta Ruszel is one of the ten appointed Delft Technology Fellows

Wioletta Ruszel

Assistant Professor, Applied Probability Department,

Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science

One of the ten appointed Delft Technology Fellows, Ruszel feels that “women are taken seriously as scientists at TU Delft.” She observed more women around her faculty, especially in the statistics department, “but less so in computer science and analysis.”

Inspiring change: “Mathematics is often misrepresented by being associated with males, asocial behaviour and autism. Take movies such as A Beautiful Mind and X+Y. Apart from leaving out the females, it seems mathematicians have to be dour and are not allowed to have a sense of humour,” she said. An active member of DEWIS, Ruszel also volunteers to talk to young girls in schools and camps about a career in science. She believes that women need good role models in the field. She was particularly motivated by her only female professor, Dr. Sylvie Roelly at Potsdam University. “She was inspiring, open and nice and had five children. Her example showed that a female academic career was possible”, said Ruszel.

Key issues: Dutch social norms are also a career barrier. Ruszel, who has one day off to stay home, said this of the mind-set: “If you work more than three days you are called a bad mother, making a scientific career for a women impossible.”

International experience: “France, Italy and

Portugal have university systems that provide permanent academic positions with the necessary stability for women to have families.” In her native Poland women combining work and family has been accepted, but there she would be taken less seriously as a scientist and senior

positions would be closed to her.

Merle De Kreuk volunteers with girls to help change stereotypes about scientists

Merle De Kreuk

Assistant Professor, wastewater treatment and anaerobic digestion processes, Civil Engineering and Geosciences

De Kreuk has witnessed a lot of change over the years. In the late 90s, as a project manager and engineer at a shipyard, she was often mistaken for a secretary. While things aren’t quite so overt at TU Delft, she has seen maternity leave clauses evolve and slowly come to favour women.

Inspiring change: De Kreuk volunteers with VHTO, a nationwide initiative to reach out to young girls. During her sessions with high school girls, she found they often believe that as scientists they can’t have children and families. “From a young age girls tend to think they’re weaker at math or science. They have an image of a scientist as someone grubby, or in a hazmat suit. Someone who works alone. They have a very strange image of an engineer as a geek. We talk to them about reality and how normal we are,” she said.

Key issues: “Women want to do everything that they are judged on perfectly, and the list that scientific staff is judged on is very long. Men, on the other hand, are more confident with a 7 out of 10 score,” said De Kreuk. It doesn’t help that perceptions play against them. “Most boards and

selection committees are comprised of men, and when they interview a young man they see themselves in him, but their daughters in the female candidates. Naturally this influences whom they pick.” At TU Delft, they now ensure that a woman is part of any selecting committee.

International experience: Quoting a friend, De Kreuk said that for women the world over “the years when they have to produce and publish the most work is when they have children, so they already miss out on one or the other”.

Marja Elsinga finds that women also have to prove themselves and more is expected of them.

Marja Elsinga

Full Professor of Housing Institutions & Governance, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment and President of Delft Women in Science (DEWIS)

“At TU Delft the traditional gender breakdown still holds. About 11% of professors are women. There are few women in engineering, more in the sciences and the greatest number in the design fields,” said Elsinga.

While progress is slow, she finds the recent reinvigoration of the human resource department encouraging. “HR has renewed its support for gender equality and diversity in recruitment policy.”

While the deans and the board are supportive of DEWIS, she feels a lot more needs to be done at the department level. “A lot of male professors are unaware of gender issues and disinclined to attend a course on gender awareness.”

Inspiring change: Elsinga sees gender diversity as a natural component of general diversity and sees a role for DEWIS in furthering the spread of awareness. She would also like to introduce a workshop on gender awareness at TU Delft.

Key issues: While explicit gender bias is slowly being addressed, the implicit aspects also need to be acknowledged. As an example, she cites professorial meetings. “To function in these meetings women have to adjust their behaviour to the male rules of the game.” Women also have to prove themselves and more is expected of them.

International experience: Cultural aspects make gender bias more complex. As a guest professor at a university in Shanghai, Elsinga recounted her discomfort at male dominated dinner functions where the gents dominated the proceedings with sessions of toasting.

Comments are closed.