Researchers have been using solar energy to split carbon dioxide and water into building blocks for kerosene. The news site phys.org published a review on this solar kerosene.

The leading players in the research on solar kerosene are the ETH Zurich (Department of Mechanical and Process Engineering) and Shell Global Solutions in Amsterdam. Hans Geerlings from Shell Global Solutions is also part-time Professor in the Materials for Energy Conversion and Storage group of the TU Delft Faculty of Applied Sciences. Last year, they explained the whole cycle of thermal reduction of CO2 and H20 into syngas (CO and H2) and the subsequent synthesis into aircraft fuel in the article Solar Kerosene from H2O and CO2.

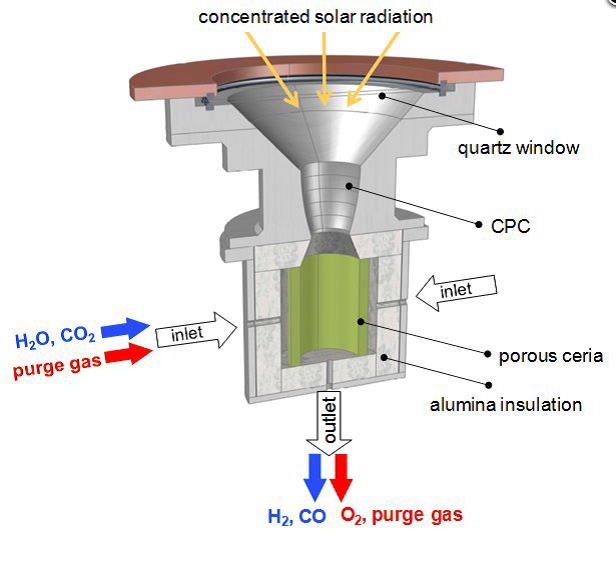

The phys.org article, Technique uses solar thermal energy to split H2O and CO2 for jet fuel, by Susan Kraemer has a reference list dating back to 2010 when the first experiments with solar thermal reactors began. Two vital factors are the extremely high operations temperature of 1,500 Celsius, and the porous catalytic material Ceria oxide that lines the reactor walls.

Postdoc researcher Dr Philippe Furler is quoted explaining the process. “Ceria is a state-of-the-art material. It can release a certain amount of its oxygen and then, in the reduced state, it has the capability of splitting water and CO2.” This step takes place at 1,500 Celsius. The second step, in which Ceria binds oxygen from CO2 and H2O, also takes place at 1,000 Celsius. Furler again: “Now it (Ceria) takes up the oxygen, and thereby resumes its initial state. The product, a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, can then be extracted from the reactor.”

That gas mixture, also known as syngas, can be synthesised into liquid hydrocarbons by the Fischer-Tropsch process. This catalytic process, developed in 1925, is a commercially available technology.

Professor Andrzej Stankiewicz (Intensified reaction and separation systems at the Faculty of 3mE) comments that solar reactors have been proven to work. Not only in the research above, but also in work at Caltech and Sandia Labs. The extreme working temperature is achieved by concentrating large amounts of solar radiation into a small reactor chamber. The conversion efficiency (solar to fuel) of the reactor is currently 5%. The team aims to raise the efficiency to 15% with an advanced system of heat recovery. Stankiewicz could not comment on this because of the lack of details. Phys.org says that the process has an efficiency potential of 30%.

According to the SOLAR-JET project coordinator, one square kilometre of heliostats in the desert concentrating the sun onto a solar reactor could generate 20,000 litres of kerosene a day. According to Boeing, a passenger plane consumes 15,000 litres per hour. So, one would need 10 km2 to allow two Atlantic crossings. Now, how much desert would one need to fuel the approximately 100,000 flights a day we currently have?

Stankiewicz has another observation: “These techniques use CO2 as a raw material, but the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, currently about 400 parts per million, is much too low to be of practical use. “

In a reaction, Professor Hans Geerlings says he doesn’t agree that atmospheric CO2 cannot be used. He currently prepares a paper on atmospheric CO2 capture.

Heb je een vraag of opmerking over dit artikel?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.