With antibiotic resistance on the rise, Delft microbiologist Stan Brouns is planning to battle bacterial infections with viruses. With crowdfunding, he intends to develop phage therapy.

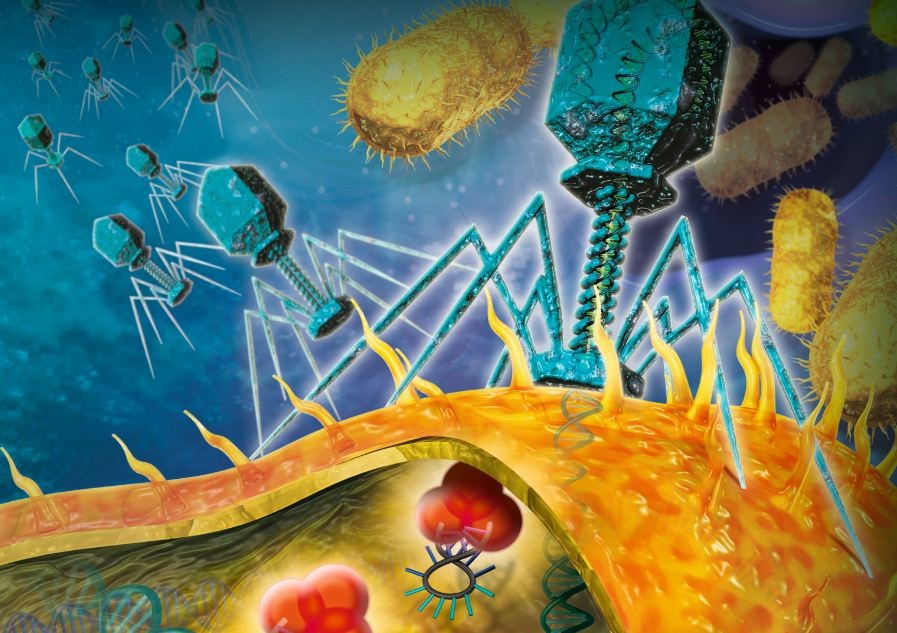

The microorganisms that Dr Stan Brouns of the Bionanoscience department wants to work with are called bacteriophages. These viruses are the natural enemies of bacteria. Their potential lies in the fact that they evolve simultaneously with bacteria. If these latter develop features that protect them from phages, the phages will adapt as well in a continuous evolutionary battle. This is something that antibiotics obviously cannot do.

There is a natural predator for each bacterial strain, a phage that only feasts on that specific strain. Sewage water in particular is a good place to look for new potentially therapeutic phages.

‘Phage therapy is not based on miracles’

Phage therapy is not common at the moment because there are no clinical studies that prove that this therapy works, writes Brouns on a website which he launched recently to announce his plans for starting up a phage therapy and the crowdfunding to enable him to do so. “Phage therapy, however, has solid scientific grounding and is not based on miracles,” the researcher adds. He is hoping to receive three million euros to work out his plans.

The website was jammed for a while last week. Brouns was interviewed by the Dutch TV programme ‘Dokters van morgen’ that centred on phages. That probably attracted a lot of visitors to his site.

Phage therapy has been around for over a century. Bacteriophages were discovered in 1915. They were immediately recognised as a way forward for the eradication of bacterial infections. Especially important was the foundation in 1923 of the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia, which was devoted to developing phage therapy. The therapy is now being used in Russia, Georgia and Poland. The rest of the world lost interest after antibiotics were discovered in 1941.

Phages as a last resort

With antibiotic resistance on the rise, there is now renewed interest in the western world. But still the use of it is very limited. In The Netherlands for instance, bacteriophages may only be administered in extreme cases, when patients are on the brink of dying from an infection and antibiotics cannot help. That has to change, asserts Brouns. Hence his project.

Brouns plans to use the three million euros as starting capital to set up a large bacteriophage library; test administering techniques; set up a diagnostic centre; start a facility to culture phages on a large scale; and lobby for his cause in politics and in the medical and insurance world. That is quite a list for only three million euros. Unfortunately, Brouns was not available to comment on his plans to Delta.

In The Netherlands, the Delft researcher may be at the forefront of phage research – his lab already has quite a lot of experience with these viruses – but not far from here, in Belgium, there is a man who already has quite some experience with the actual therapy. Jean Paul Pirnay is head of the bacteriophage lab of the Koning Astrid military hospital in Brussels. He has used phages to cure several patients who were on the brink of dying.

‘Phages cannot exterminate all the bacteria’

He is very positive about this therapy. But he also wants to temper expectations. “The downside of phages is that they need bacteria to survive. This means they cannot exterminate all the bacteria in a patient,” or so he told the Flemish newspaper De Standaard last year. “We don’t think they can completely replace antibiotics. But they can be a good addition. With dangerous infections and antibiotic resistant bacteria, phages can help weaken the bacteria, making them susceptible again to antibiotics.”

Comments are closed.