Imagine a runway at sea, a moored harbour or even a floating city. PhD student Jan van Kessel calculated a way to make mega-floaters more resilient.

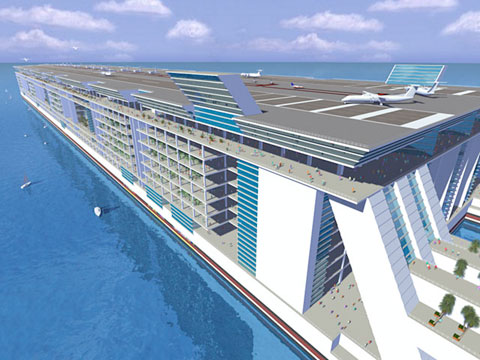

Like so many other technical novelties, mega-floaters or floating islands were first described by Jules Verne in his 1895 novel ‘L’ile à hélice’ (or ‘Propelled island’). Fast-forward a century and the same dream is now called ‘Freedom Ship’, whose website describes a floating city that dwarfs the Queen Mary. The structure would be 1.5 kilometres long, 250 metres wide and more than 100 metres high. It would house hotels, shopping malls and leisure facilities, all topped by a small landing strip.

Enough of dreams, for floating superstructures have already been built. The largest so far was a kilometre-long floating airstrip in Tokyo Bay. At 149 million dollars, it was a costly experiment to see how well a floating airstrip would perform. Experiments performed after its completion in 1999 showed that there were no significant differences between a land-based runway and a floating one. Quod erat demonstrandum. Afterwards, this structure was dismantled and parts of it are still in use as car parks, fishing piers, fair grounds and an information centre.

PhD student, Jan van Kessel (cum laude Maritime Engineering, 2004), thinks that thus far mega-floaters have been rather conventional. He points out that breakwaters have always sheltered large floating structures from the waves. In his thesis, entitled ‘Aircushion supported Mega-Floaters’, he presents and calculates another form of floating entirely. Not an immense barge, but rather a bottomless box, floating on a ‘cushion’ of encapsulated air. Think of a shoebox without its lid, turned upside down and placed in the water. Van Kessel shows that the forces on a floating shoebox structure are about half of those on a conventional closed barge. Besides, he argues, the use of aircushions to make things float offshore isn’t new. Forty years ago, gigantic oil storage tanks in Dubai were constructed on land, lifted by pressurised air and towed to their offshore locations, eventually sinking on the spot.

In his thesis Van Kessel develops a method to calculate the dynamic behaviour of mega-floaters in waves. His numerical model calculates how the waves pass under the floating structure and how the air pressure varies. He then compares the outcome of the calculations with tank tests using a bottomless barge measuring 2.5 by 0.7 metres, and concludes there is a fitting correspondence between theory and test. What’s more, the aircushion-supported barge performs better than a conventional closed box. The roll and pitch motions are smaller (the waves can pass more freely underneath the structure) and the wave-induced bending motions are halved.

Ships are assumed to be stiff by conventional hydromechanics, and incapable of being deformed by wave-induced forces. But mega-floaters are so large that one can no longer assume that the whole structure will retain its form. Van Kessel therefore repeated his calculations for a flexible barge – a box that could bend with the waves. With an impressive array of matrices, summations and numerical hydroelastic calculations, Van Kessel shows that aircushions reduce the vertical bending of the structure (in comparison with a closed structure), but they also move the spots of the highest bending from mid-ship towards stern and bow. The torsion of the (flexible) structure caused by incoming oblique waves may be too large, but – according to Van Kessel – that can easily be fixed by adapting the design.

Now let’s get practical. The most logical mega-floating structure needed in the near future is an offshore airstrip, Van Kessel argues. At 3800 metres, its runway would be as long as Schiphol’s longest runway. The most plausible place for this airstrip would be off the coast of Singapore, since it is a densely populated city-state that has little else to extend to other than the seas. Taking the local wave regime into consideration, Van Kessel shows once more that the bending moments on the structure in the open seas would be reduced by two thirds if the builders would simply leave out the bottom of the barge.

Jan van Kessel will defend his thesis on February 1, 2010.

De enige echte traditie die het muziekgezelschap Krashna Musika kent, is de jaarlijkse voetbalwedstrijd tussen koor en orkest. Inzet is de Kick Admiraal Cup. “Een prachtige, witte plastic bokaal, vernoemd naar onze dirigent”, vertelt orkestcommissaris Afke Laarakker.

Sinds 1989 is de wedstrijd vaste prik op het jaarlijkse repetitieweekend. Dan vertoeft de hele club in het Brabantse Someren op een gigantische kampeerboerderij met een grote schuur waarin gerepeteerd kan worden. Op een veldje, met aan beide einden twee palen die als doel fungeren, proberen dan tweemaal veertig muzikanten elkaar sportief de loef af te steken.

Naar de wedstrijd wordt maanden van tevoren uitgekeken, bevestigt Laarakker. “Er wordt veel over gesproken. Als je verliest krijg je dat zeker een jaar lang te horen. Het zijn spectaculaire, fanatieke wedstrijden. Bijna elke keer vallen er gewonden, omdat iedereen ongetraind is. Er heerst een enorme chaos, niemand weet wat hij aan het doen is. Mensen die bij het koor én orkest zitten spelen voor beide teams. Een scheidsrechter? Nee, die is er niet.”

Volgens de inscripties op de beker komen de beste voetballers meestal uit het orkest. “We hebben ook nog eens samen tegen een Duits orkest gevoetbald. Toen heeft Nederland gewonnen.” De trofee is een echt Krashna-item. “Hij lijkt op een bloemenvaas, met zo’n hoge dunne steel, ongeveer veertig centimeter hoog. Echt zo’n tuincentrumding.” Naamgever Daan Admiraal loopt al 27 jaar rond bij de muziekvereniging. “De wedstrijd zal ooit bedoeld zijn om zijn gratie te ontvangen. Hij is degene die al die tijd is gebleven.” De volgende krachtmeting staat gepland in het repetitieweekend van mei.

Comments are closed.