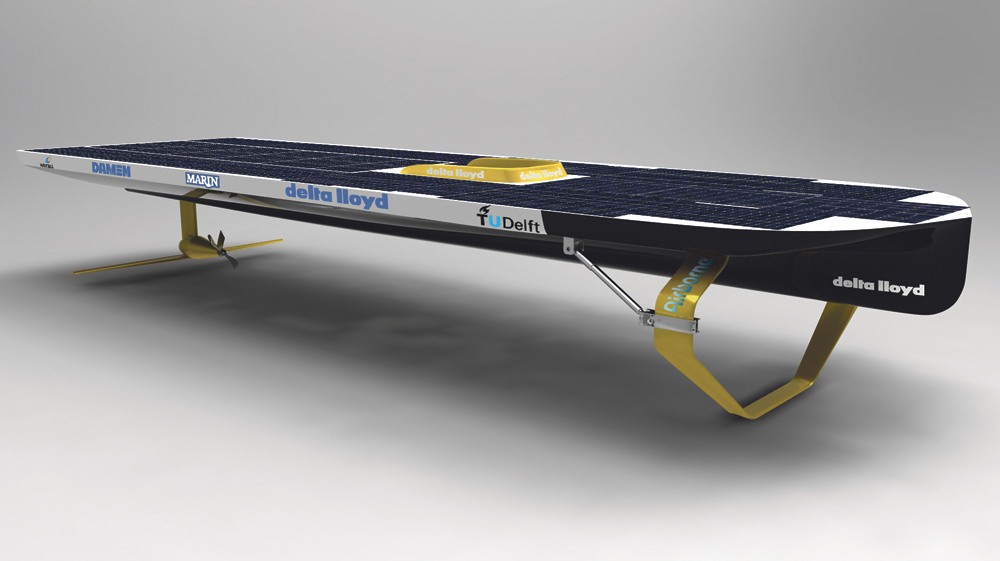

Like its predecessor, the Delft solar boat will rely on hydrofoils to lift it out of the water and allow speeds up to 36 kilometres per hour or more. But this time, the fins will be auto-adjusting.

The student team is preparing their vessel for the fourth Frisian solar boat race, which will take place from July 8-4. The biannual event is a race for solar-powered boats over 220 kilometres, inspired by the legendary skating event called the Elfstedentocht.

Two years ago the TU Delft team featured hydrofoils for the first time. And although their boat did reach a top speed of 36 km/h, it came in third over all. That was a bit of a bummer after the victories at the first two editions in 2006 and 2008.

The main difference with two years ago is that this time the hydrofoils will be adjustable. The T-fin at the rear will be outfitted with flaps that govern the lift (last time, the tail didn’t have enough lift to get the stern off the water). The V-shaped front foil will be attached at two hinges. Two electrically powered cylinders will adjust its angle towards the oncoming water and hence the lift. Both this angle and the position of the rear flaps will be automatically controlled by a software system that uses the speed as its main input. From 12 km/h up, the boat will lift off from the water.

Less visible improvements include the hydrofoil’s profile, improved electronics and a slightly different hull-shape. Mechanical engineering student Erik Jansen estimates the ship could run up to 40 km/hr.

Over the next few weeks parts will be coming in from special composite workshops and wharfs to be assembled in Delft. The team aims for the first tests on the waters of the Schiekanaal by the end of May.

Delta Lloyd Solar Boat 2012

length 5.93 m

Beam 1.80 m

Depth 0.60 m

Weight 135 kg

solar power 1,750 Wp

engine power 4000 W

www.deltalloydsolarboat.nl

www.dongenergysolarchallenge.nl

The use of so-called ‘plant production units’ is seen as a breakthrough in the horticultural world. Because there’s no longer a need for daylight, fruits and vegetables can grow wherever you need them: on a large scale in an old factory or an empty office building in the middle of town. Also in the IBM factory along the A4 highway, which has been tenantless for 11 years now. The first garden office of the Netherlands will be established here. If successful, garden offices could be the perfect solution for all empty offices in Amsterdam: in total 1.4 million square metres.

Director of the TU Delft Botanical Garden, Bob Ursem (faculty of Applied Sciences; department of Biotechnology) sounds enthusiastic about this idea: “Great fun!” he says. “Since the location is not important anymore, offices are good places for gardens like this. Besides, I think this technology should be applied in every glass-enclosed structure where plants are cultivated, for it is far more sustainable than the average glasshouse.”

So how sustainable is this concept really? According to Ursem, the regular lights used in glasshouses use 420 Watt, while LED grow-lights use 20 Watt: a reduction of factor 200. In addition, LED lights don’t get hot, meaning the plants sweat less, which cuts the amount of water in half. So, the technology saves energy as well as water. Furthermore, LEDs are also more ‘light efficient’, which perhaps requires a bit more explanation.

Green plants normally use sunlight for their photosynthesis. This natural light consists of all colors, just as the artificial yellow light in an ordinary glasshouse does. However, a plant mainly uses only two colors to grow: blue light (with a wave length of 420 nanometre) and red light (within the spectrum of 640 to 680 nanometre). Red light is lower in energy than blue light, so both lights are used in a proportion of 5:1. This is why LED grow-lights shine purple.

PlantLab, a company in Den Bosch, developed the technology that will be used in the IBM factory. It claims to be the first company in the world that has succeeded to grow – in addition to leaf crops – fruit-bearing plants without light. Ursem isn’t familiar with this company; however, in 2009, he won the World Economic Forum’s highest innovation prize for his LED technology for plants. He collaborated with Lemnis Lighting B.V., a Dutch company located in Barneveld, and made their LED light suitable for a horticultural application. So Ursem’s research seems to be the foundation for the garden office.

The IBM factory might be the first garden office, but it’s not the first place in the Netherlands where LED lighting is being used to grow plants. Koppert Cress, Europe’s largest micro vegetable nursery in Monster, already uses LED in its greenhouse complex. In December 2010, the first cress was harvested using the LED technology from Lemnis Lighting.

Ursem only foresees one drawback. “Horticulturists are not the only ones who will be interested in saving energy, water and light” he says. “Also growers of cannabis want these LED-based plant production units. Everything that you develop has a counterpart.”

Comments are closed.