The DARE team presented its design for a new rocket last Tuesday. More stable than its blown-up predecessor, Stratos IV should reach the edge of space at 100 km.

Krijn de Kievit (l) and Eoghan Gilleran with a Stratos III model. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

The Delft Aerospace Rocket Engineering (DARE) team very much builds upon the experiences of previous teams. That’s why the current team started by studying the blow-up that terminated the flight of Stratos III after just 20 seconds.

Analysis of the accident showed that the rapid spin of the rocket had caused resonance in the pitch, resulting in the fuselage breaking up. Rocket engineers call this phenomenon a roll-pitch coupling.

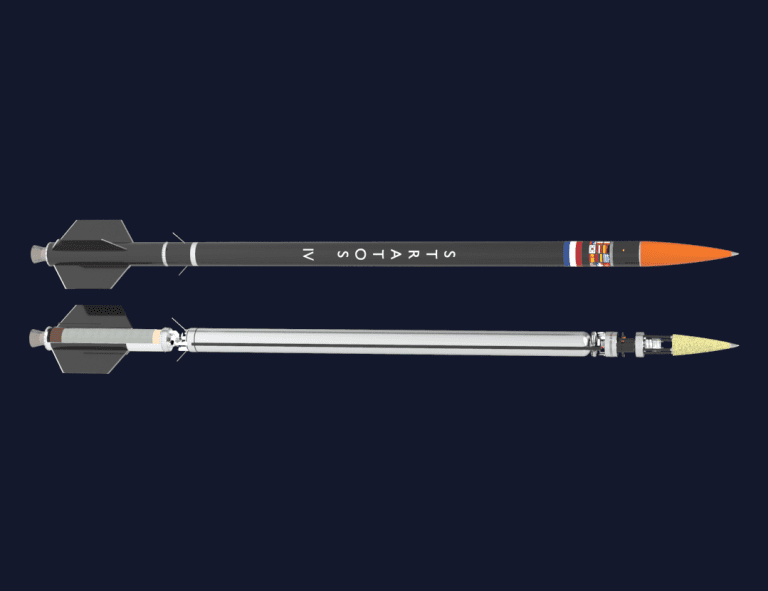

Stratos IV design. (Image: DARE)

Stratos IV design. (Image: DARE)The new team, led by team manager Eoghan Gilleran and chief engineer Krijn de Kievit, decided to improve the design of Stratos III, but keep the hybrid engine mostly as it was. A roll control system will be used to counteract the spin (or roll). It consists of a gyro sensor to detect the spinning of the rocket around its longitudinal axis, and four thrusters aimed sideways to stop the roll. Longer fins should also reduce the roll. Further, several adaptations will make the fuselage more rigid.

Besides being more rigid, the Stratos IV will also be lighter. Or, as Krijn de Kievit explains, the team has minimised mass to reach a higher altitude. A lot of weight has been lost by replacing the graphite nozzle by a mostly titanium one. That took 10 kilograms off the scale.

According to calculations, Stratos IV should be able to reach the edge of space at 100 kilometres altitude. That would be a very stiff climb after 12.5 km by Stratos I in 2009, and 21.5 km by Stratos II+ in 2015. And it would certainly smash the current record by the competition in Stuttgart (30 km by HEROS 3 in 2016).

Meanwhile, construction by a large team of 15 full-time and 60 part-time students has begun. The roll-out is planned for May 2019. The rocket will then be dismantled for transport to South Africa. Because the team is aiming to reach a higher altitude, the Stratos IV cannot be launched from the edge of Spain like its predecessor. Instead, it will take off from the Denel Overberg test range, from where it has a free path all the way down to the South Pole.

“The roll-control is our first step to controlled rocketry,” says Eoghan Gilleran. “Next will be pitch and yaw.” These controls will enable the rocket to stay on course regardless of the wind speeds higher up in the atmosphere.

Heb je een vraag of opmerking over dit artikel?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.