A wave of protests has swept across China in the last two weeks. Chinese students at TU Delft too demonstrated, though in a different way.

Protesters hold protest signs in Shanghai. (Photo: Cindy Huijgen)

TU Delft student Ronghua got goosebumps when she opened WeChat, a mobile platform popular among the Chinese. Almost every photo, film or text on her timeline was about demonstrations that had broken out shortly before. They were angry texts by people who were fed up with the Covid regulations or photos or videos of demonstrators with banners with slogans and blank sheets of paper held up. Ronghua saw that there were a lot of students among them. “I thought to myself that people of my generation dared say something publicly for the first time,” she says.

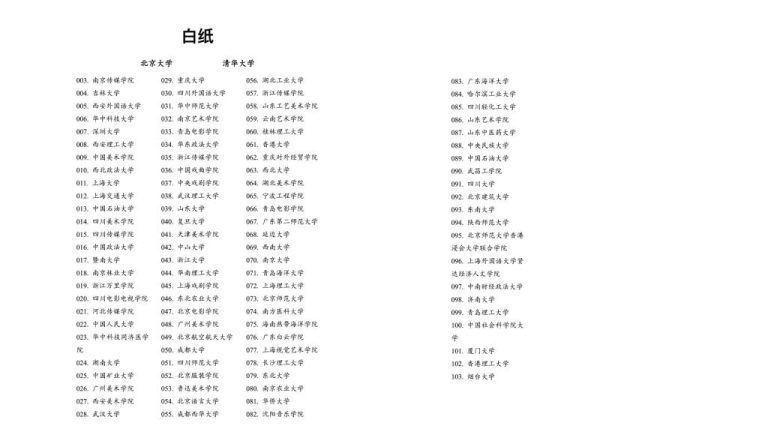

Shortly afterwards when Ronghua put down her phone, images of baizhi gaige (‘the white paper revolution’) circulated around the world. While foreign journalists attended protests in city centres in large numbers, they were not at demonstrations on China’s campuses. Nevertheless, it is possible to get an impression of what happened there over the last one-and-a-half weeks on social media. According to journalists from University World News, who analysed messages, videos and photos on social media, there were definitely demonstrations at 130 universities. They varied from a few students who held up blank sheets of paper to gatherings of dozens of students. On Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, lists circulated with the names of universities where, according to Chinese internet users, protests were held.

Fear of reprisals

Ronghua is not her real name. The TU Delft student is worried that she or her family may have problems if the Chinese authorities found out that she had talked to a Dutch journalist. Other Chinese students that Delta spoke to share that fear. They too have false names. Why did they respond to an interview request? “This is my way of doing something,” says Ronghua. Student Jinhua says that “My fellow students in China have problems if they talk to the press. As I went abroad I have a little more freedom, even if I am being watched. By talking to you, I can make the story of my demonstrating fellow students better known abroad.”

The cause of the protests was a fire in a block of flats in which 10 residents lost their lives as they were in Covid lockdown. The protests quickly turned to anti Chinese Covid restrictions. The country has had a ‘zero Covid’ policy, with measures varying across province, region or city. Many demonstrators consider the measures unnecessarily strict. In some cities entire neighbourhoods were hermetically sealed if there was even one positive case. In other cities, residents first had to do a Covid tet before they could travel by public transport.

‘My generation needs to speak up’

The Chinese students at TU Delft see that the restrictions were equally strict on campuses in China. Students there live in quite close quarters, with four to twelve students often sharing one room. “Whole buildings go into lockdown at my friends’ universities if just one student is tested positive. That is crazy. We don’t believe that the measures are in line with the risk of infection,” says student Leung. TU Delft student Viktor explained that “At friends’ university there was a complete lockdown last week. They took lectures online and the university delivered food to the door.”

The Chinese have demonstrated several times against the Covid measures this year. In mid-November residents of the Chinese city of Guangzhou protested (in Dutch) and in mid-October an angry resident hung a banner with protest slogans from a bridge in Beijing. Why have so many students joined the nationwide wave of protests now? According to Jinhua this is mostly because of the bleak outlook of the Covid policy. “People are sick of it. The measures are not only strict, but there is no certainty as to when they will end. People in quarantine bear the brunt, but students too are suffering. I have read a lot of posts on Weibo by students saying that their mental health is suffering. I too – when I was still living in China – had to be in lockdown for six months. I could only talk to my parents and grandparents. It was hard as I really wanted to see my friends and classmates.”

TU Delft student Thi sees the protests in a wider context. He believes that it is his generation’s duty to speak out. “We were all born at the end of the last century or the beginning of this one. In contrast to our parents, we have never known poverty or hunger. We grew up in affluence with the idea that the future will always be better. But now, with all these Covid restrictions, this does not appear to be the case. At the same time, we have seen more censorship in recent years and less freedom of expression. I am afraid that the generation after us will end up in a sort of North Korea if we do not speak out now.”

Some of the students that Delta spoke to were Chinese students who had gathered in Amsterdam last week to demonstrate. A few TU Delft students joined, although not everyone dared do so. “I was in Amsterdam, but did not join in,” says Thi. “There are often students at demonstrations who could inform the authorities about you.” Earlier this week a Chinese student told the NOS (in Dutch) broadcaster that one of her fellow students had problems after he took part in a protest. “The police broke into his grandmother’s house and forced her to videocall him. They then threatened him.”

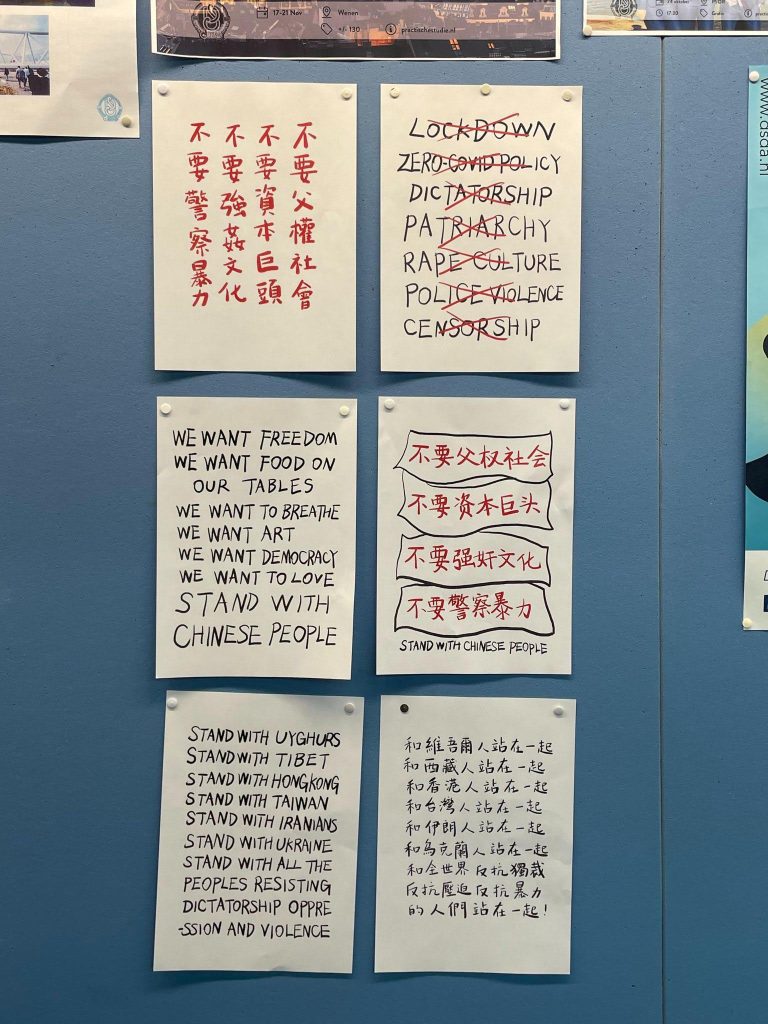

Chinese TU Delft students are making themselves heard in other ways too. Students report protest posters against China’s Covid policy hanging in different places. The posters point to a wider protest movement as well. They draw attention to Tibetans, Uighurs and demand democracy. Delta’s Editorial Office has not seen the posters itself, but has received a photo.

At the University of Groningen (in Dutch) and universities in other countries including Australia and Great Britain there are similar posters. Whether and if so to what extent the movement in China is wider is unclear. While some demonstrators in Shanghai shout anti-Government slogans, it is unclear whether other demonstrators support these, say correspondents.

The campus protests began Saturday evening, Nov. 26, at a university in the Chinese city of Nanjing, two days after the fire. By Sunday afternoon, students also gathered at other Chinese campuses, including that of the prestigious Tsinghua University. Although foreign journalists were not present at the campus protests, TU alumnus Martijn de Geus saw firsthand what happened at Tsinghua. He is an assistant professor there and lives a few hundred meters from where students were demonstrating. De Geus talks to Delta in a personal capacity. “Here, the demonstration was mainly a kind of gathering where students took turns to step up a rise to voice their opinions. The atmosphere was calm.” He estimates dozens of students were present.

Gatherings at Tsinghua

According to both De Geus and international media, the administrators of Tsinghua started to hold gatherings about Covid shortly after the demonstration started. “Students could ask questions and express their opinions,” says De Geus. “About 50 students could attend the first meeting physically. Thousands of students followed the meeting online. They asked questions about the effects of Covid on their lessons or lab experiments as well as about the demonstrations themselves. They wanted to know if there would be any negative consequences for those taking part in the protests.” According to international media such as University World News, the university administrators promised that the students who demonstrated would not have any problems, although they were not prepared to confirm this in writing. In the days that followed, the university held similar meetings. “That took the sting out of the tail,” says De Geus.

Things were handled more harshly in other places. Demonstrators in several cities were arrested. A lot of posts about the protests were also censored. “Many of the articles that I read were no longer available within a few hours,” says Jinhua.

You pay the bill later

On Nov. 11, the central Chinese government already implemented relaxations in covid policy. According to Chinese students in Delft, the protests have accelerated further relaxations. “For example, since this week my mother no longer has to take a test if she wants to travel by subway,” Jinhua said. On Sunday, several major cities such as Shenzhen and Shanghai backtracked on their covid measures, and on Wednesday China’s National Health Commission announced a 10-point plan. Buildings and neighborhoods will no longer be completely shut down once a resident tests positive for corona. The testing regime will also become less stringent.

Still, according to international press agencies, students at Nanjing Tech University and Wuhan University started new protests on Monday the 5th of december. They protested because they still had to be in lockdown when one positive Covid test was found.

Chinese students at TU Delft find it hard to predict what will happen in China in the next few weeks. “I do not think that people will start demonstrating again. The measures have been eased, so the objective has been reached,” says Viktor. TU Delft student Lifen fears that taking part in the protests could have unforeseen consequences for students. “They could still be arrested at some point. Or they may find it harder to get a job in the future as they are known as ‘troublemakers’. In China we have a saying, qiūhòusuànzhàng, which means that you pay the bill later.”

Delta approached many Chinese students for this article. Some of them were willing to cooperate. Some of the meetings were face to face, others were digital. The real names of the students are known to Delta’s Editorial Office. Some Chinese universities in this article have not been named. This was done at the request of the relevant students.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

a.m.debruijn@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.