Kite-powered winches could replace diesel generators on islands. The Delft Kitepower group prepares for a launch on Curaçao. This week, they’ll attend the AWEC2019 in Glasgow.

Powerkite ready for launch at UV Valkenburg. (Photo: Henri Werij)

Airborne wind energy, or kite power, is growing ever since Professor Wubbo Ockels (1946-2014) launched the idea of generating power by flying kites early this century. Kitepower in Delft is both an academic research group and a start-up, with people freely mingling in between them. The research group led by Dr. Roland Schmehl (Faculty of Aerospace Engineering) employs six PhD researchers. The Kitepower company, led by Johannes Peschel, and housed on the top floors of the AE building, has over 20 people on staff.

Kites keep getting bigger. (Photo: Kitepower)

Kites keep getting bigger. (Photo: Kitepower)Growth is also evident from the kite sizes. Ockels’ prototype from 2010 had an area of 25 m2, delivering 20 kW of power. Now the kite size has jumped up via 40 and 60 to 100 m2. The largest kite is expected to deliver 100 kW, the maximum power of the current winch.

Winch and kite in Valkenburg. (Photo: Henri Werij)

Winch and kite in Valkenburg. (Photo: Henri Werij)Field tests take place on the Unmanned Valley Valkenburg, a former military airfield. Two 100 kW winches and kites now share the airspace with drone-based start-ups. Kitepower develops and tests the kite control units (KCU) there – the kite’s brain that controls the direction of flight and the force on the Dyneema winch line by towing and reeling the control lines.

Until recently, test flights used to be limited to 5 hours because of the KCU’s rechargeable battery. Recently, the control unit has been fitted with its own little on-board wind turbine, which allows the kite to fly as long as there is wind – in principle. The longest test run thus far was 10,5 hours, after which the crew wanted to go home and took down the kite.

(Photo: Kitepower)

(Photo: Kitepower)Field tests should reveal how closely kites can fly together; how much noise they make; how birds react to the giant screens zipping through the sky, and how to share the airspace with other users. Schmehl’s group studies synchronised flying as a means to fit more kites into the same airspace.

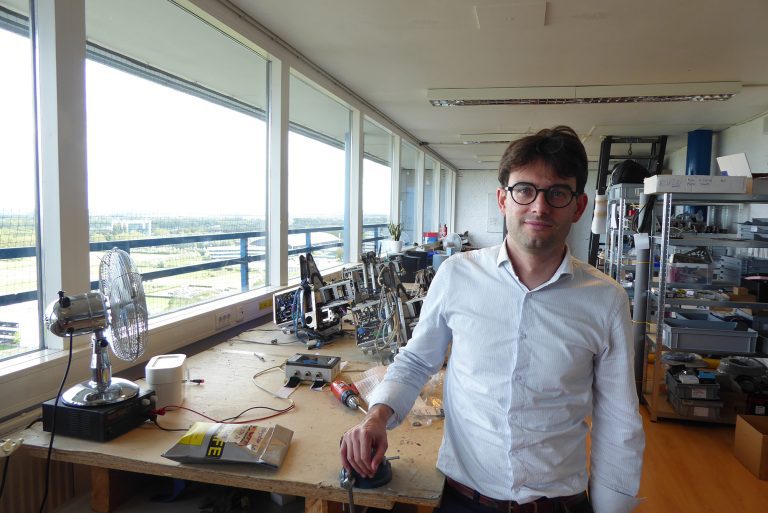

Joep Breuer in Kitepower lab, Delft. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

Joep Breuer in Kitepower lab, Delft. (Photo: Jos Wassink)His commercial counterpart Joep Breuer, who graduated from Wubbo Ockels’ kite group in 2006, is preparing Kitepower’s first commercial launch. A power kite is planned as part of a wind park near Curaçao by 2021.

“The power price on the islands is higher than on the mainland,” explains Kitepower’s technical manager Joep Breuer. “A power price of 0.15-0.45 euro per kilowatt-hour allows us to make a competitive offer.” That’s why Breuer expects that power kites will complement, and later perhaps replace, diesel power grids on islands. “We replace steel by intelligence,” quips Breuer.

At the two-day Airborne Wind Energy Conference (AWEC) 2019 in Glasgow this week, researchers from Delft will meet international colleagues from leading industries Ampyx and Makani. They will discuss topics like the role of wind power in the energy transition, and practical issues like the control of cross wind and the automatic launching and landing of kites.

Delft researchers are also looking ahead to the Torque conference, organised by Dr. Simon Watson, Professor of wind energy at the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering in May 2020. The first edition of this ‘largest and most renowned scientific energy conference’ took place in Delft 16 years ago.

Ockels’ first kite lab on the 14th floor of the AE building. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

Ockels’ first kite lab on the 14th floor of the AE building. (Photo: Jos Wassink)Kitepower is one of the three dreams of Wubbo Ockels that have taken root in Delft. The others are the Vattenfal Solar Team and the TU Delft Solar Boat Team.

Related articles:

- Three reasons why kite power is better than wind turbines (2017)

- Kite power about to take off (2017)

- Lightweight wind energy (2017)

Heb je een vraag of opmerking over dit artikel?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.