Fourteen years removed from the September 11th attacks, our lives are dominated by security measures. Stepping on board a commercial flight often requires passing through a full body scanner.

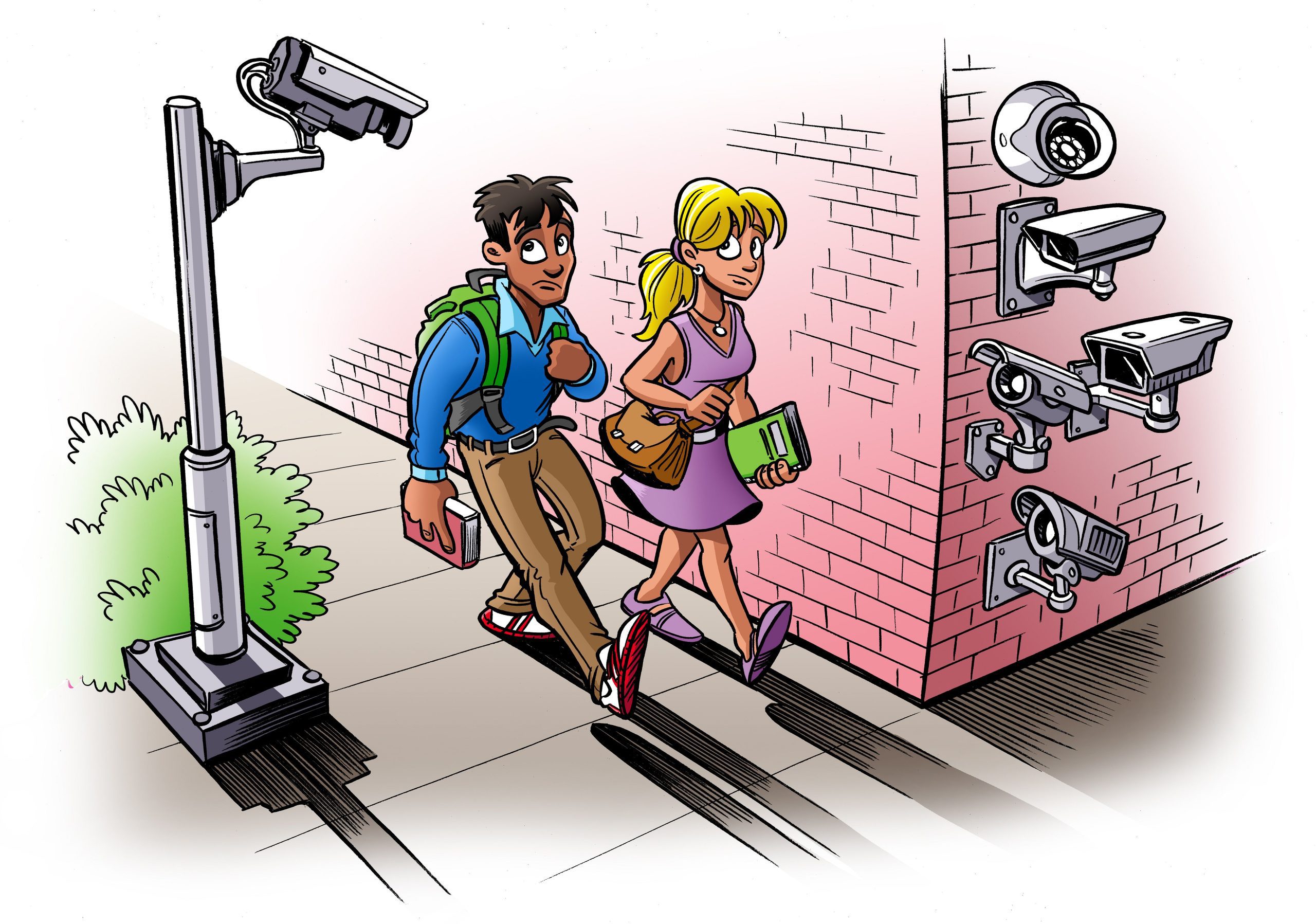

Security cameras can be found everywhere from university campuses to street corners. In a world where various government agencies attempt to track our phone calls and emails, where do we draw the line?

On August 21, 2015, a gunman opened fire while on board the Thalys, a high-speed train heading from Amsterdam to Paris. He was subdued by other passengers and fortunately there were no fatalities. Those who were able to prevent his attack were

later hailed as heroes while officials all across Europe scrambled to come up with an appropriate response. In the days that followed, pundits and politicians alike wondered: do we need more security measures in the continent’s train stations? At this moment, it’s still possible to ride on the Thalys without having your luggage or body scanned in the same manner you would in an airport. You can also pass through the gates at Delft’s railway station and freely travel across the Netherlands without having to worry about anything beyond getting pestered by a conductor for your ticket.

But this still begs the question: should more be done to secure Europe’s train stations and, if so, what? Many might argue that forcing daily rail commuters to have their bags scanned before they board a train would present a logistical nightmare of epic proportions. This sort of measure could create bottlenecks in busier hubs and convince more and more passengers to drive to work instead, thus creating frustrating rush hour traffic jams on the Netherlands’ highways. Worst of all, these measures might not actually prevent another terrorist attack.

Employing workable security measures that won’t dramatically impact the lives of everyday citizens is a colossal task that government officials around the world have been grappling with for years now. On the topic of making train stations safer, Dr. Pieter van Gelder from TU Delft’s Safety and Security Institute suggested employing heightened methods only at certain times. “If there are indications for imminent threat, we should indeed increase the security,” he said. “Not only with more police surveillance (and dogs), but also by using high tech surveillance, such as cameras and other types of sensors.”

Aarmed guards

Others have argued that placing armed guards on trains would be an effective method of combating would-be terrorists, but TU Delft Programme Manager Klaas Pieter van der Tempel is skeptical. “No doubt it would be nice to have a heavily armed soldier or police officer on your train if it comes under attack,” he said. “But consider the chance of that happening and the sheer amount of trains riding around the country at any moment. I doubt that it’s possible to protect everyone. And what sort of message would this send to society?”

But how best to avoid gridlock and chaotic scenes in train stations around the country? “There is still a challenge here for developing better non-intrusive sensoring techniques, which can keep the flow [of passengers] ongoing,” Van Gelder said. “[We need] pattern recognition algorithms that respect the privacy of people while detecting strange patterns in baggage, behavior, etc. To increase human surveillance is very difficult, given the limited resources. There is a need for better surveillance technology.”

As Van Gelder noted, logistical quagmires and the limits of existing technology make devising effective security systems incredibly difficult. Perhaps one of the best methods to combat terrorism in the present day are everyday people themselves.

“We should also realize that the public has a role in keeping safety and security at high levels, and not only the government and the railway sector,” Van Gelder said. “Public participation such as ‘social control’ and helping each other in case of incidents really helps, as was shown in the Thalys incident for instance.” On the other hand, the average rail commuter is hardly a rugged counter terrorism agent a la Jack Bauer or James Bond.

Perhaps providing the public with basic defence training through television programmes or government sponsored classes would be a step in the right direction. “Personally, I would prefer to learn clear and rational steps that I could take if I ever ended up in a situation like that on [a train],” Van der Tempel said. “Do you run? Yell? Counter-attack? Pull on the emergency brakes and storm out through the nearest door or window? I’m not an ex-Marine and I’ve never even slapped anyone in the face before. Right now I have no idea.”

Big Brother

The debate over how to best secure borders while keeping tabs on the communications and recruitment methods of terrorist cells rages on. Many advocates are arguing for increased measures while the other side is concerned with infringements on civil liberties and western society turning into something straight of George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984. The efforts of government agencies to zero in on terrorist networks via the mass surveillance of phone and internet traffic has been especially criticised in recent years. “Massive surveillance without privacy preservation techniques is indeed needlessly invasive,” Dr. van Gelder said. “Although targeted surveillance in case of reasonable suspicion, which may prevent possible attacks, is in my view absolutely justifiable.”

Van der Tempel is even more critical of these measures. “The way we implement these programmes now has made our government and the military industrial complex that supplies it into a literal security state, where everyone is a potential suspect,” he said. “But how much do we know about the ones watching us? Where is the transparency? One thing I know is that I’d rather die in a free country than be safe in a virtual tyranny.” As the Netherlands and other European nations face concerns beyond national security like austerity proposals and infrastructural maintenance, is it time to roll back some of their more costly security measures? “If you would stop the body scans at airports now, you would attract potential terrorists. It is some kind of gridlock where we can’t get out since we have introduced it,” Dr. van Gelder said. As with any government policy, once it’s put into practice it can be very difficult to repeal it.

More substantial threats

Doing so can be like trying to stuff a genie back into a bottle, as any American politician grappling with components of the controversial USA Freedom Act will tell you. If this topic weren’t already complex enough, there’s also the question of whether or not there are things that pose a greater threat to Europe’s citizens than terrorists.

“This may sound odd, but I would like to see the government protect civilians from much more substantial threats in our society than religious fanatics,” van der Tempel said “Irresponsibility and lack of accountability in the financial sector, ubiquitous marketing to children (obesity is not just an American thing anymore), media manipulation through monopolies and corporate control, the weapons industry, harmful pesticides, fossil fuel subsidies, and so on. One of the biggest killers is the traffic accidents, about 600 each year,” Van Gelder said. “But also preventable accidents in hospitals lead to an estimated 1,000 casualties, or more, each year. Maybe those are two domains where more tax money should go. Autonomous vehicles might be a development which may reduce the victims in traffic significantly. The same in the healthcare sector, by using more robotics and clever information technology solutions.”

Needless to say, the debates over these procedures and methods are likely to continue for years to come. The challenges faced by officials are countless and resources are finite. Perhaps the biggest question of all remains: should we be focusing our attention elsewhere?

Comments are closed.