Angelo Vermeulen, a TU Delft researcher in the TPM faculty, was in the last 6% of those selected to become an ESA astronaut. He was not selected in the end. Why did he join?

TU Delft researcher Angelo Vermeulen during his Mars simulation on Hawaii in 2013. (Photo: Yajaira Sierra Sastre)

As a space researcher and biologist at TU Delft, Angelo Vermeulen designs ecosystems for long stays in space. He is also an artist and an aspiring astronaut. He worked on a simulation for the American space agency NASA in 2013 for space travel to Mars.

Last year, he was one of almost 23,000 people who signed up for the selection of astronauts by ESA, the European equivalent of NASA. He was one of only 6% of the people who got through the first round, but did not progress to the second selection round.

Where did you get your interest in space travel?

“I have always been interested in it. As a child I was fascinated by space travel and biology. I read a lot about it. When I was 12, a friend and I started a scientific magazine that I copied and sold at school. The first article I wrote was about the development of space suits for astronauts. So my interest lies very deep.

The serious idea that I wanted to become an astronaut is a lot newer. I studied biology and wrote a dissertation. While working on the dissertation, I started a photography course. This grew into practising art. I combine art, biology and technology. I will be in a museum putting together an exhibition on one day, and the next I will be working on computer simulations at TU Delft.”

One of the futuristic installations Vermeulen built together with the SEADS collective. (Photo: Angelo Vermeulen)

One of the futuristic installations Vermeulen built together with the SEADS collective. (Photo: Angelo Vermeulen)How did you end up in aerospace?

“My first step in aerospace was completely unexpected. I started incorporating my scientific background in my art. I made futuristic installations, for example, from recycled computers linked to plants and single-celled algae. I presented this project all over the world.”

“The founder of one of the ESA research programmes, Max Mergeay, saw my work in 2008 at a presentation afternoon in Brussels. He was working on the MELiSSA system, a circular ecosystem in space that will keep people alive. He was so interested in my installation that he wanted us to work together.

I became interested in aerospace through my contact with that research group. Unfortunately, the new astronaut selection had just finished, so I had to wait until the next round in 2021.”

What did you do in the meantime?

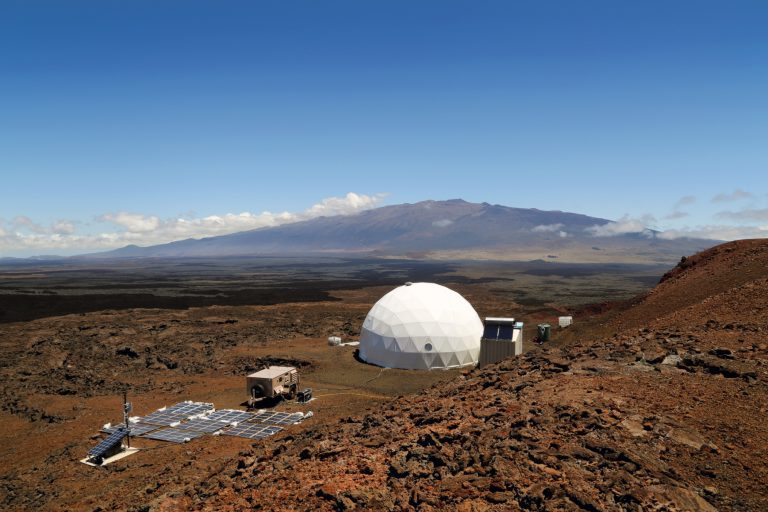

“I spotted an open call for the HI-SEAS mission on a website for space news. This is an American Mars simulation on Hawaii. Just over 700 people responded and after a series of selection rounds, I was chosen along with five others.

The simulation was a special experience. You are in a confined space with the other people who you get to know really well. As the captain, it was my job to keep the group together. I organised times when we shared experiences of the week gone by and how you dealt with them. I learned a lot about leadership during that mission.”

The dome used during the HI-SEAS simulation on Hawaii. (Photo: Angelo vermeulen)

The dome used during the HI-SEAS simulation on Hawaii. (Photo: Angelo vermeulen)It was a simulation. How did you make it seem real?

“That was a challenge. You are continually aware that it was fake. From the outside, it looked like we were staying in a white dome, but from the inside it looked very ordinary, with tables and beds from Walmart and IKEA. And when you went outside, you of course saw the blue sky and sometimes saw a bird flying overhead.”

“Luckily we did not see any other people outside the space station. We were in a very remote place at the foot of a volcano in Hawaii. When things were delivered, we thought up a scenario in which the things ‘landed’ on the surface of Mars. We had to go outside to pick them up, but could only do so when we could not see the lorry anymore.”

Your next opportunity came in 2021 with ESA’s astronaut training programme. How did the selection go?

“In contrast to NASA, ESA does not look for new astronauts every four years. At 49 I was at the age limit. This is clearly visible in the group that was ultimately selected – they are all in their early 30s. But I wanted to try.

You go through six stages in the procedure. The first is a screening for the basic qualities. In that stage, a longlist of about 17,000 potential candidates was made from the 23,000 applicants. In the second stage, about 92% of the applicants did not get through, But I was still in.

With the remaining 1400 candidates I went into a group phase in Hamburg. In groups of about a hundred applicants we did cognitive, motoric and personality tests. That’s where I was left out. But they don’t tell you why not.”

Vermeulen working in the HI-SEAS mission dome. (Photo: Simon Engler)

Vermeulen working in the HI-SEAS mission dome. (Photo: Simon Engler)What did you think when you heard you were not selected?

“I had actually assumed that I would not be an ESA astronaut. I am at the age limit after all. But naturally I would have liked to have gotten a bit further in the selection process. On the one hand, I hoped to meet colleagues, and on the other hand, I hoped to get a better understanding of what they were looking for in an astronaut and how they tested potential astronauts.”

For my work for TU Delft, I am thinking about the future of humans in space. I am designing virtual ecosystems and living environments for long-term stays in space. The people need to keep themselves going, and the raw materials need to be used on site. This may sound abstract, but I like to see how the procedure on how to become an astronaut can be part of this.”

What do you think of the selection of the people who will go into space?

“The last 30 or 40 candidates are all equally good as they stood all tests. But there is an element of politics involved. For example, there may not be 10 French people and of the 17 selected, almost half are women. This is very progressive of the aerospace sector.”

In an interview with the NOS news service (in Dutch) you said that you will not give up your space ambitions. What are you thinking of?

“A career at ESA is no longer possible, I think. But there are now commercial flights and commercial space stations are being developed. There might be options there, but this is more a dream than a clear plan.”

Also read:

- Travelling among the stars about one of the starships Vermeulen is designing

- Making meals on Mars about Vermeulens’ expectancies for the Hawaii expedition he did in 2013

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

K.S.vanderWal@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.