A special clay tablet, the size of a soap bar, was scanned in TU Delft’s micro CT-scanner last week. Archaeologists wanted to compare the text on the clay envelope with the text on the tablet inside.

Curator Dr Rients de Boer brought in three clay tablets from the Netherlands Institute for the Near East (NINO) last week. The most intriguing was a 4,000-year-old tablet measuring five by five centimetres and 2.5 centimetres thick, consisting of an inner tablet surrounded by a clay envelope. In the Girsu region, now southern Iraq where these tablets came from, cuneiform script on clay tablets served administrative purposes to keep track of harvests and commercial transactions.

In a video (below), De Boer explains that enclosed clay tablets were used for fraud prevention. When the clay was still wet, it was very easy to change the figures on a tablet. Once sealed within an envelope, such fraudulent practices became a lot harder.

The micro-CT scanner in the TU Delft building for Civil Engineering and Geosciences was originally bought for studying geomaterials (soil, rock, concrete, asphalt, etc…). Nowadays, however, Assistant Professor Dominique Ngan-Tillard frequently receives requests to scan archaeological objects.

Samples the size of a brick can be placed in the machine. During the 1.5 hour scan, the clay tablet was rotated step by step while 1,440 X-ray photos were made. This resulted in a 3D dataset (8.2 gigabyte) with a spatial resolution of 30 micrometres.

Rients de Boer and Dominique Ngan-Tillard looking at cross section. (Photo: Sam Rentmeester)

Rients de Boer and Dominique Ngan-Tillard looking at cross section. (Photo: Sam Rentmeester)The first cross-sections confirmed a clay tablet within a clay envelope. How the Mesopotamians succeeded in closing the envelope without making it stick to the tablet is still a mystery.

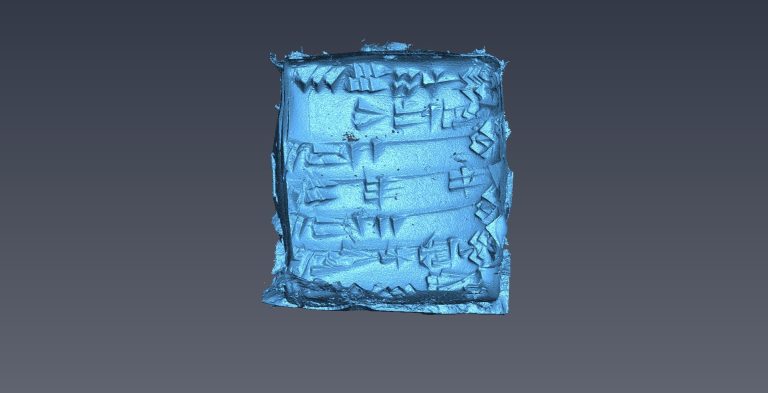

Reconstruction inner clay tablet. (Image: Dominique Ngan-Tillard/TU Delft)

Reconstruction inner clay tablet. (Image: Dominique Ngan-Tillard/TU Delft)Dr Ngan-Tillard scanned through all the cross sections, labelling the void between the two clay volumes. By doing this, she selected the surface of the hidden clay tablet, which she later reconstructed as a 3D surface. The blue colour of her reconstruction is a considered choice. She doesn’t want the reconstruction to look like a photo of the object (in which case brown-yellow would have been a better choice).

A few days later, Dr de Boer produced his preliminary translation in which he identifies the tablet as an “Administrative tablet from Girsu (southern Iraq), concerning the receipt of a quantity of sesame delivered by Lu-Ningirsu and received by his brother Ur-Abba. The text is written in Sumerian with the cuneiform script.”

The tablet describes the delivery of fresh sesame. The envelope says 15,280 litres, while the inside tablet specifies 11,050 litres the first time, and 4,230 litres the second time. The numbers add perfectly. One could say that this ancient fraud protection has worked.

- The tablets, and their 3D-printed counterparts, will be part of the Scanning for Syria exhibition in the RMO museum, Leiden, opening beginning of June.

Video made by Dr. Dominique Ngan-Tillard

Heb je een vraag of opmerking over dit artikel?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.