At this very moment, the best sailors in the world are fighting against heavy storms and huge waves in the Volvo Ocean Race. Seven carbon racing yachts are participating, including two flying the Dutch flag. One of these, Team Brunel, is participating in research on ocean pollution. TU Delft alumni Michiel Muller and Ronald Bolijn are helping them.

Photos: Jasper van Staveren, Team Brunel/Volvo Ocean Race

It is early November, and Michiel Muller has just arrived in Lisbon. In the harbour on the river Taag, the teams of the Volvo Ocean Race are preparing for the voyage to Cape Town, the first leg of their race around the world. Muller and Bolijn are visiting Team Brunel to discuss plans, opportunities and progress. They are representing their company, Abel Sensors, which develops and manufactures smart wireless sensors that can communicate directly through their own cloud platform using LoRa and NB-IoT technology. This means the sensors are suitable for Smart Everything: smart cities, industries, buildings, mobility and living environments.

‘Our sensor will measure concentrations of contaminating particles all over the world’

Muller and Bolijn recently became involved in the rough and ready world of salty seas, immense waves and toiling 24/7 under the toughest conditions thanks to one of their investors. “The investment fund Embrace Tech Startups has close ties with Brunel,” explains Muller on the pier in Lisbon. “That’s what brought us together. Ronald is an experienced sailor and has since joined the crew on several voyages.” The two alumni stepped into this project with a clear objective and a mission to promote sustainability. “We are investigating the potential of an on-board sensor that can measure the quantity of contaminating particles, such as plastic, in seawater,” explains Muller. “We are also trying to find a method to measure the tiniest plastic particles. These are invisible to the naked eye and can easily enter the food chain. These measurements can provide us with insight into the total amount of pollution in the world’s seas.”

‘Internal’ solution

These carbon yachts are pure speed machines. Anything that can negatively affect performance must be removed. This means that the sensors must be light and they certainly may not disrupt the streamlining of the perfectly smooth hull. So, Muller and Bolijn are testing an ‘internal’ solution. “We are currently considering a small pipe that branches off of one of the engine pipes. This pipe sucks in seawater for cooling and discharges it again. We plan to install our sensor in such a pipe for the next edition of the Volvo Ocean Race. It will be fitted inside the hull so that it doesn’t affect the streamlining. The sensor contains a wireless controller we developed ourselves that logs the sensor data and GPS location every 5 minutes. The controller is in sleep mode most of the time and only uses a few milliwatts of power. When the yacht approaches a coast, it will send all the logged data to the shore. This will provide a complete data set of the quantities and locations of contaminants along the route of the race.”

‘The sensor may not bring performance advantages or disadvantages’

The sensor itself is still under development. This is being done entirely in-house by the company’s own personnel using their own components. This means they are not yet exactly sure how it will work. “We do know that the system will use a built-in battery that lasts one year and so will easily last the entire race. It will be installed in the pipe in a compact waterproof and shockproof housing. The device will include embedded software that has been programmed by our team. Whenever the ship approaches land, it will send us the data using our own cloud platform. We will store this information on one of our servers. We will analyse the data using a dashboard that displays a map of the world.”

Muller makes it clear that developing a properly functioning, secure and reliable sensor will be a real challenge. “The most difficult part is to achieve the required high level of sensor measurement quality and reliability. This is why we are first taking samples in all the seas and oceans the team will pass during the race around the world. We will use the samples for our first tests and they will function as reference data for future tests.”

Turn the tide on plastic

This research is important, but of course it is also important that it does not affect the race. The Volvo Ocean Race is a one design race, which means that all teams race with technically identical yachts that also weigh almost exactly the same. Any changes to the vessel are subject to strict rules and stringent inspections, and this also applies to added sensors. “Modifications are not allowed to bring performance advantages or disadvantages. For the next edition of the race, we will examine whether additional measures are required to be able to fit the sensor without altering the weight of the yacht.” They may even have to fit the entire fleet with one of the ‘TU Delft’ sensors.

And what do the sailors think of it? “The sailors of Team Brunel and the other teams are very committed to the environment and the health of the oceans,’ says Muller. They have seen with their own eyes how polluted the seas are and how important our work is. It is for good reason that one of the mottos of this race is Turn the tide on plastic. They are happy to help by gathering data to provide us with more knowledge about pollution in the oceans.”

Michiel Muller (left) and Ronald Bolijn. (Photo: Jasper van Staveren)

Michiel Muller (left) and Ronald Bolijn. (Photo: Jasper van Staveren)Michiel Muller (34) studied Transport, Infrastructures and Logistics with the Department of Civil Engineering and Geosciences. He focused on traffic models and the influence of policy decisions on infrastructure projects. His final project in 2009 involved calibrating traffic models for the road network of Zuid-Holland.

Ronald Bolijn (31) graduated from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science in 2013 with a Master’s in Transport Engineering. His final project involved studying how to increase the productivity of KLM’s baggage handling processes at Schiphol Airport.

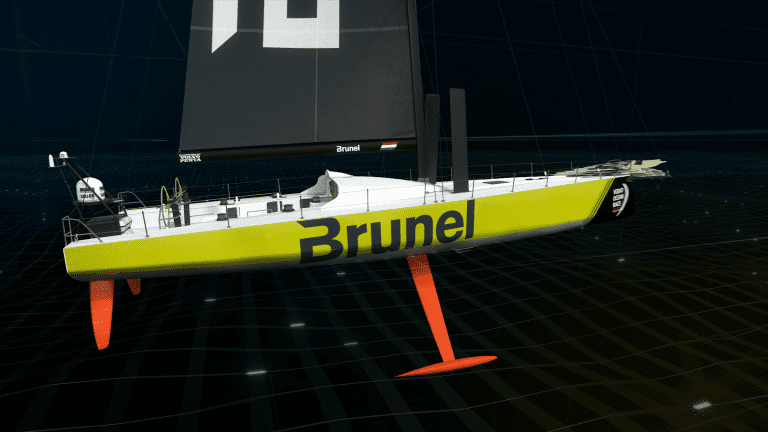

One design VO65. (Image: Team Brunel/Volvo Ocean Race)

One design VO65. (Image: Team Brunel/Volvo Ocean Race)Ever since the Volvo Ocean Race of 2014-15, all sailing teams have been required to use completely identical yachts. The Volvo Ocean 65 was especially designed for this race. The VO65 is participating for the second time in the 2017–18 edition of the race. Seven teams are participating in total. The race started on 14 October in Alicante. After eleven stages and eight months, the race around the world will end in Scheveningen in June 2018.

- Hull length: 20.37 metres

- Length overall: 22.14 metres

- Mast height: 0.30 metres

- Bowsprit: 2.14 metres

- Mainsail:163 m2

- Masthead Code 0: 305 m2

- Jib:133 m2

- Max. running sail area: 578 m2

- Net weight:12,500 kg

- Draught: 4.78 metres

- Max. speed: approx. 35 knots (65 km/h)

Leonard van den Berg

Comments are closed.