Fewer and fewer Dutch students are entering the English-language Aerospace Engineering bachelor’s programme. The EEMCS Faculty was able to admit more Dutch students for Computer Science and Engineering through a Dutch-English variant. How does this control work?

Tentamenzaal aan de Drebbelweg. (Foto: Thijs van Reeuwijk)

Universities like to keep control over the influx of foreign students. Outgoing Minister Dijkgraaf of Education submitted the Internationalisation in Balance bill to that effect at the end of May 2024.

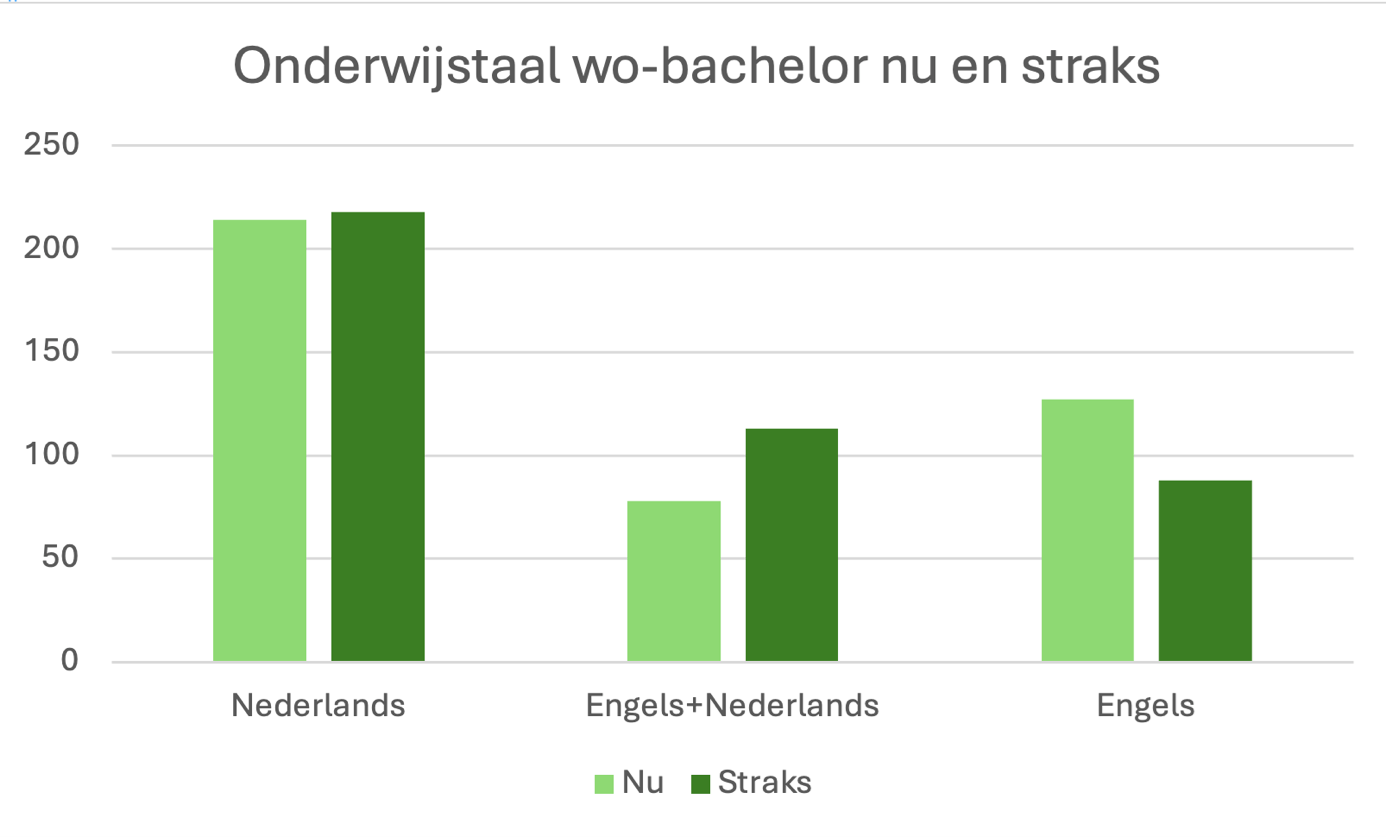

In early April, in anticipation of the Bill, the Universities of the Netherlands (UNL) umbrella organisation announced that the number of fully English-language variants in the 419 bachelor’s programmes would be reduced by a third and that Dutch-language variants would be created for 35 English-language bachelors. Delta wrote that ’35 Bachelor programmes to get Dutch-taught variant, but not in Delft’.

Earlier, Delta had reported that the new language policy would at most affect the Aerospace Engineering bachelor’s programme, but would only take effect in the 2025-2026 academic year at the earliest. Other English-language bachelors at TU Delft, such as Applied Earth Sciences and Nanobiology with an intake of 85 and 120 students respectively, were too small to make a difference, Vice-Rector Rob Mudde explained at the time. Starting in the 2023-2024 academic year, the bachelor’s in Computer Science and Engineering introduced a bilingual Dutch-English track in addition to the English track. Those involved are very positive about this.

‘Abolish Dutch ASAP’

Education Director Joris Melkert (Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, AE) remembers vividly that in the late 1990s, the review committee urged all Dutch-language bachelor programmes to be ended as soon as possible. After all, aerospace is an international discipline par excellence. That may be easy to say, but it then took 15 years before the programme was fully English-language. In part this was because extra lecturers had to be recruited and sitting lecturers had to go on courses. So it is no wonder that Melkert and his staff are not eager to set up Dutch bachelors.

‘International students are better at maths and physics’

At the same time, they do see the unwanted side effects of the English-language programme. There are 2,900 applications every year for 440 places. So 85% of applications are unsuccessful. And increasingly, it is the Dutch students who do not make it.

Melkert says that “We see that the proportion of international students is increasing. This is because international students are better at maths and physics. At Dutch secondary schools, the content of the material for the final exam for maths has halved over the past 30 years and for physics it has decreased by about 40%. We are now seeing the consequences of this.”

Additional means

Getting more Dutch students in the programme will only succeed if there are additional means, Melkert says. “If the Government would say that 40% of the places be reserved for Dutch students, that would help. But the question is whether such a thing would ever be included in the law.”

Earlier, Rector Tim van der Hagen also advocated quotas for the number of international and Dutch students in popular undergraduate programmes. But even then it turned out that professors of education law see no benefits in these ideas. They say that you cannot state that a study programme now has enough German, French or whatever nationality students as this is forbidden on the grounds of discrimination.

Shock

The Computer Science and Engineering programme had a similar dynamic. In 2018, it made sense to switch the bachelor’s to English because of the growing need for software engineers and an English-language course is accessible to more people. Moreover, the teaching materials were already in English and for most alumni, the work field is also English-speaking.

Enrolment shot up from 400 to 850 students when it first opened in 2022. “That was a shock for all the teaching staff,” says Director of Education Annoesjka Cabo (Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science). A numerus fixus of first 500 and later 550 places, was then imposed. It then turned out that suddenly far fewer Dutch students were being admitted.

‘I fear that a Dutch-language or mixed-language variant is going to be labelled as inferior’

Cabo does not immediately want to link this to the disappointing scores on the PISA test, but she also points to the relatively low number of hours of mathematics lessons at Dutch secondary schools. So how do you ensure that Dutch youngsters can still go to TU Delft to study Computer Science, even if they have the ‘misfortune’ of coming from a Dutch secondary school? That was her motivation.

Bilingual bachelor

The solution was sought in a bilingual Dutch-English programme where part of the teaching, project work and communication are in Dutch. Thus, in 2023, the bilingual Dutch-English track appeared alongside the English-language Computer Science and Engineering programme. “The bilingual track is ideal for students looking for jobs in tax or government departments, because a lot of computer engineers are needed there too,” Cabo said.

The impact on the student population has been significant. In the year before the introduction (reference date 1 December 2022), about three-quarters of the students were from abroad and one quarter from the Netherlands (73% international, 27% national). One year later, that ratio was almost half-half (54% international, 46% national).

Cabo is happy with the introduction of the mixed variant, but stresses that the preparation took a lot of effort on the part of Education and Student Affairs and, of course, teachers. It took an estimated one and a half years.

Less qualified students

Could a mixed bachelor’s also work at AE to steer the intake? “I fear that a Dutch-language or mixed-language variant is very quickly going to be labelled as inferior,” Melkert responds. Hiring someone on the basis of their nationality means that you are knowingly accepting less qualified students, he explains.

‘We will probably get fewer students in the Dutch track’

“When we gradually introduced the English-language programme, we saw time and again that there was more demand than supply. We saw that the quality of the programme went up.” He points to the BSA yield which is higher at AE than at TU Delft’s bachelor programmes without a numerus fixus. In other words, the introduction of the English-language variant has raised the quality of undergraduate education at AE. So why would you want to go back to a Dutch-language variant?

Limited influence

Moreover, steering Dutch intake in the Dutch-English programme appears to be limited. Last year, there was a neat 50-50 split between the bilingual Dutch-English track and the full-English track. But this year, there are fewer enrolments for the bilingual track. “So we will probably get fewer students in the bilingual track. Not because we don’t want to accept them, but because they don’t apply,” Cabo says.

Her explanation is that Dutch students also apply for the English-language track because they think it is more prestigious. “That was also the problem at AE in the past,” Cabo says. “That’s why they then decided to just make it one English-language programme there.” Which brings us back to the review committee’s recommendation 25 years ago.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.