For many people, Venus is nothing more than a bright dot in the sky. But not for geochemist and experimental petrologist Edgar Steenstra. He wants to understand how the channels on Venus that are thousands of kilometers long were formed. And since this month, TU Delft has the equipment needed to investigate this.

PhD candidates Jaap Jorritsma and Guus Aerts at work in the new planet lab. (Photo: Edda Heinsman)

This article in 1 minute

- A new laboratory has been opened, the Planet lab

- The lab is specifically for conducting experiments under high pressure and temperature.

- Geochemist and experimental petrologist Edgar Steenstra is now starting to use it.

- Together with PhD students Jaap Jorritsma and Guus Aerts, Steenstra is taking the very first measurements: calibrating a 1,500-kilogram press.

- With the new equipment, they can heat and pressurize materials in such a way that they can simulate processes deep inside planets and even create diamonds.

- Ultimately, Steenstra wants to know how the channels on Venus that are thousands of kilometers long were formed, as no one has any idea how they came to be.

- Other questions that remain to be answered: Under what conditions were the moon and asteroids formed? To what extent do (exo)planets evaporate? And what did the first crust of our Earth look like?

We walk through the aircraft hall, where it is tempting to stop and look at everything, but we have a mission: the high-pressure/temperature lab, which was put into use this month. Geochemist and experimental petrologist Edgar Steenstra enthusiastically gestures as he shows us the latest additions. A high-temperature rheometer, where they liquefy rock. A huge gas mixing installation to simulate planetary atmospheres, with effective extraction of toxic gases.

“On Venus, it smells like rotten eggs,” warns Steenstra. Fortunately, there is no sign of that here. He points: “Detection equipment will be added for when there is a leak. And a device for thermogravimetric analysis, the high-pressure TGA, will be installed here. This will allow us to literally simulate the atmosphere of Venus and analyze the reactions with rocks in situ. We put a piece of simulated Venusian rock in it and see how it reacts with the simulated atmosphere, temperature, and pressure.”

Venus is a mysterious planet. It resembles Earth in terms of size and composition, but why is Venus so hot with such a toxic atmosphere? Were there ever oceans? Why does Venus rotate in the opposite direction? What is actually inside the planet? Are there active volcanoes?

New lab to prepare for future space missions

Starting in 2030, ESA’s EnVision space probe will investigate these so far unanswered questions. To prepare for this and other future space missions as thoroughly as possible, a new laboratory was opened last month at Aerospace Engineering: the Delft High Pressure/Temperature Lab for Planetary Materials.

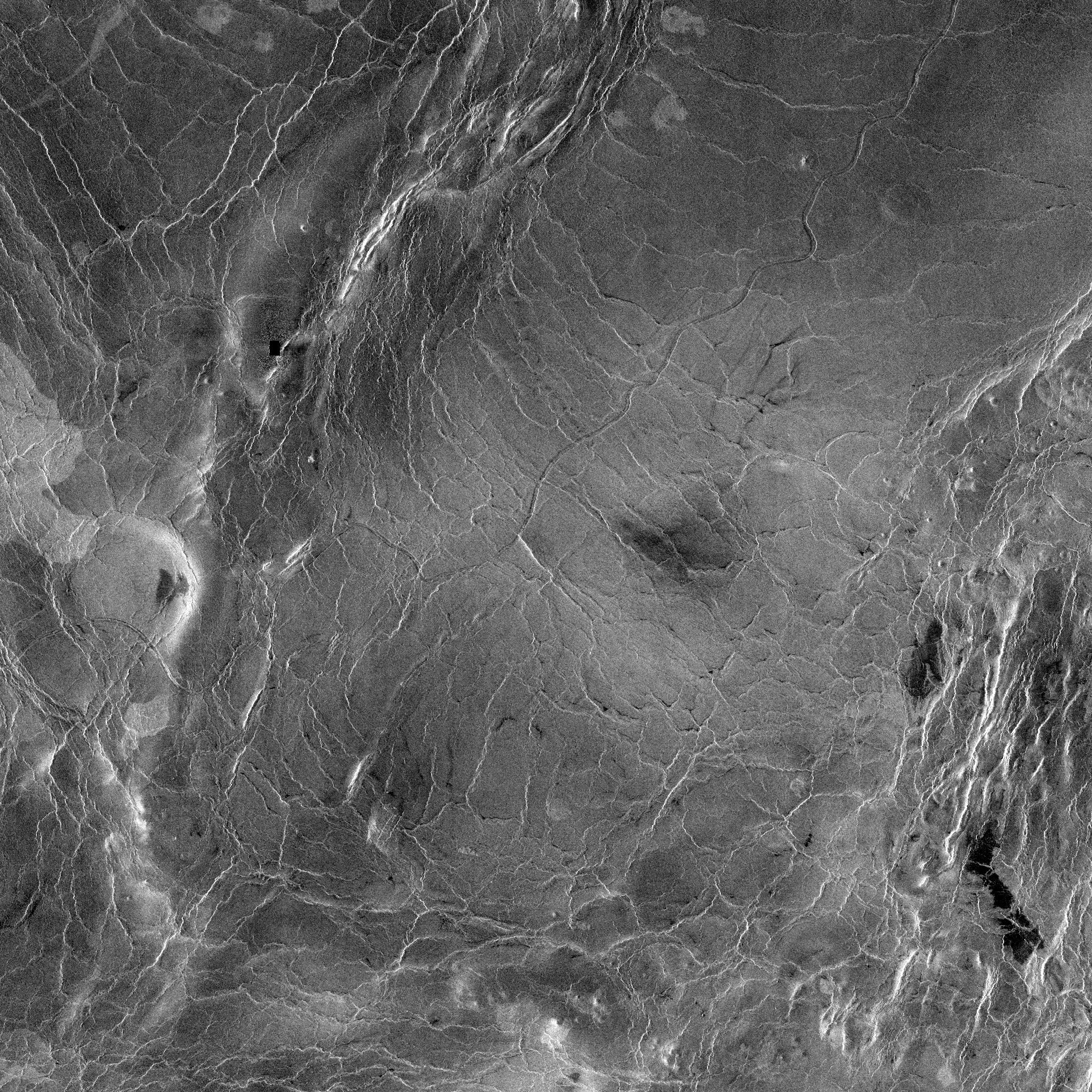

“Channels on Venus are the longest volcanic channels in the solar system,” says Steenstra, pointing to a gray meandering stripe on his screen. The images were taken by the Magellan probe, which mapped the mysterious planet Venus, shrouded in thick clouds, using radar images from 1990 to 1994. Steenstra suspects that “very exotic volcanism” formed the channels. “If you look at the geometry, you would think liquid water. But it is far too hot on Venus for that. What type of magma becomes so extremely liquid and how does it continue to flow for so long?”

In addition to the mysterious flows, Steenstra also wants to investigate other things in the new lab. What other ‘high-temperature processes’ in the solar system do the researchers want to understand? Steenstra sums it up: ‘Under what conditions was the moon formed? Or asteroids? To what extent do (exo)planets evaporate? What did the first crust on our Earth look like? In February, a new PhD candidate will start looking at how this first rock crust on Earth was formed. If we know more about the early Earth, that will also teach us about the evolution of other planets. And vice versa.”

Making diamonds

The equipment Steenstra will be experimenting with, operates under enormous pressure and temperature. Can he also use it to test crazy things? For example, what would happen to a croquette sandwich in the Earth’s interior? “If there is enough carbon in it, it will produce a very ugly synthetic diamond,” laughs Steenstra. Diamonds are formed when carbon crystallizes under very high pressure and temperature. “But we can’t achieve the pressure found at the Earth’s core. With this equipment, we can reach a depth of about 130 kilometers into the Earth, which is roughly equivalent to the centre of the moon in terms of pressure. That should be enough for an impure diamond.”

Today, a measurement with a 1500-kilogram press is on the agenda. Seeing how the device operates, the disappointing conclusion is that the ‘croquette diamond experiment’ is doomed to fail: there is barely enough room for a raisin in the container. But of course tests with croquette sandwiches are not on the agenda at all; PhD candidates Guus Aerts and Jaap Jorritsma have prepared a sample of homemade mineral. This means that the chemical composition is known exactly, which is needed to calibrate the device.

The sample is carefully placed in a small tube coated with grease so it slides smoothly into the machine’s chamber. Two wires fit nicely through a small slot to record the temperature during the experiment. It is somewhat reminiscent of assembling a bomb, especially when it becomes apparent that the piece of chewing gum that was somewhat irreverently stuck to the high-tech device actually serves a purpose and is used as a waterproof sealant to protect the experiment from cooling water.

The sample is now safely in place. Time to switch on the device. No big red button, but a huge lever. A quick check to make sure the coolant is properly connected. And then the researchers take turns pumping the lever to gradually reach exactly the right pressure. Meanwhile, the researchers keep track of the device’s status in a logbook. Today, the piece of test rock will reach 1,000 degrees Celsius and a pressure equivalent to a depth of about 100 kilometers. For comparison, the deepest borehole ever drilled reached about 12 kilometers. It is not possible to go any deeper, mainly because of the enormous pressure. “If we want to learn more about the interior of our Earth, how the Earth was formed, and how other planets work, then we need this kind of equipment,” Steenstra points out.

That is, if the brand-new machines behave as desired. The first exciting step: the sample has to be in the press machine for 24 hours, so we will continue the next day.

“The floor wasn’t flooded,” Steenstra says on the phone the next morning. He sounds somewhat relieved. “I went to check it out first thing this morning and luckily everything was still connected properly and the required pressure and temperature were being achieved.”

So the equipment seems to be working. But to calibrate the machine precisely, the rock sample needs to be examined further. “It is well known at what temperature and pressure this type of mineral transforms into another mineral. In this case, from albite to jadeite and quartz. We will be busy for a while taking various measurements to calibrate the device.”

Jade and quartz? They may not be making diamonds, but they are making gemstones. Pretty great really: creating gemstones in order to ultimately learn more about other planets.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

E.Heinsman@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.