Peter Gill, China Advisor at TU Delft, wrote West meets East. In this book he compares China, Taiwan and Singapore to Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark respectively.

(Image: Marjolein van der Veldt)

Every paragraph contains a mine of succinctly described research. In only 208 pages, Peter Gill covers all sorts of sociological and cultural subjects, and also subjects like food security, semiconductors, the energy transition and artificial intelligence in depth. Why did he write this book, and why now?

In order to write your book, you travelled to Singapore, Taiwan and China. What did this bring you?

“I was already familiar with the cultures as I had worked in the region. As I speak Mandarin, I was able to talk to a lot of people there and learned how they see things. I used the trip primarily to give my book the finishing touch. I had the support of the staff at embassies and consulates, and I brainstormed there with young people. One thing I learned was that I should make the book more personal. For this reason, I added the Making of West meets East at the end.”

Talking about the making, how long did it take to write the book?

“On paper, about two years. But my eldest daughter said ‘Dad, you should not say that it only took two years’. Almost all my free time went into it. For a long time I got up at 5 AM at weekends to write, and I used all my saved up holiday days on it. If I would add up all the hours, it would amount to at least one year of full-time research and writing.”

China has a prominent role in the book, but there already are a lot of books on China. What does your book add?

“I will answer that through someone else’s words. I recently gave West meets East to Rector Magnificus Tim van der Hagen. We had a good discussion and he was very interested. He said that a book like this did not yet exist. I think he is absolutely right. A book that compares six societies is unique. Apart from China, it’s also about Singapore, Taiwan, Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands.”

Why did you choose these six countries to compare?

“It actually began as a book about the three societies in which Mandarin is an official language. I guess it was the engineer in me that wanted to make it comparative. All these countries show interesting parallels. The Netherlands and Taiwan share four centuries of history and both are leaders in the field of semiconductors. Philips was even behind TSMC, the Taiwanese chip manufacturer. I wanted to include Denmark in the book as it is heavily involved in the energy sector. And what transpired? The sizes of Denmark’s economy and population are similar to those of Singapore. I compared Germany and China because they are the biggest economies in their respective continents. In their case, I look specifically at the car industry. Germany is still the market leader in Europe, but you see much of this is shifting. In 2022, China accounted for 60% of the worldwide sale of electric cars. I thought it was important to show this in figures and in so doing, give the hard facts.”

‘Europa is like a museum, said the Singaporean banker’

Are you hoping that your book will show the shift from West to East?

“Yes. There is still a lack of understanding in Europe that the world’s stage has shifted towards East and Southeast Asia. Westerners make up only 11% of the world’s population and the size of our economies is limited. But we still act as through we are still in the centre of everything. Countries like Singapore see Europe as an old fashioned mess. During my trip I spoke to a Singaporean banker who looks at the daily trade flows. ‘Europe is like a museum, man,’ he told me. ‘You have no energy, no commodities and all the technology is coming out of China.’ So another important message is for Europe to wake up and deal with this shift politically and economically.”

Isn’t the European Union doing this already, for example with strategies targeting China?

“Yes, but the emphasis is now on decoupling. On closing our doors and doing everything for ourselves. But many reports say that our supply chains are so inextricably linked that a strategy like this means that you’re actually undermining yourself. My message is that we need each other, especially in terms of the energy transition. Whether you like it or not, China has plenty of long-term plans that they will roll out. For example, it is working on having a complete hydrogen energy industry by 2035. And, in line with its plans, it has made so many innovations with solar panels that in 2025 the world will be virtually dependent on China for solar panel production.”

Should Europe work more in the long term?

“I think it should. I was pleased when we got an Undersecretary for Mining in 2022, but surprised when it turned out that his main job was the gas field in Groningen. Why is he not looking further into the future? The Netherlands only recently started exploring critical raw materials. We are 20 years too late. When I was in China in 1993, I already met people from countries in Africa who spoke fluent Mandarin as they had received a scholarship. This helped China access a cobalt mine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as the French have a uranium mine in Niger. Over the years, China has become the largest producer of many critical raw materials. China happily makes 50 year plans while we in the Netherlands have difficulty looking 10 years ahead. Apart from this, I believe that industrial policy (in Dutch) is hugely important. Taiwan, Singapore and China all have industry to thank for their strong economic position.”

In those countries, the industrial policy was and/or is still accompanied by an authoritative form of government. What would this look like in the Netherlands?

“I don’t have all the answers. But I do see that some things could be better. We could combine industrial policy with a long term vision and execute it in accordance with our own norms and values. This would mean defining where we want to be in 30 years and what sectors or companies are important in this. If we want to be a CO2 neutral society, we will not achieve it with a few wind farms. They will be amortised in 20 to 25 years. So what should we do and, in particular, where do we get the materials from?”

Students were involved in the book too. Were any from TU Delft?

Students were involved in the book too. Were any from TU Delft?

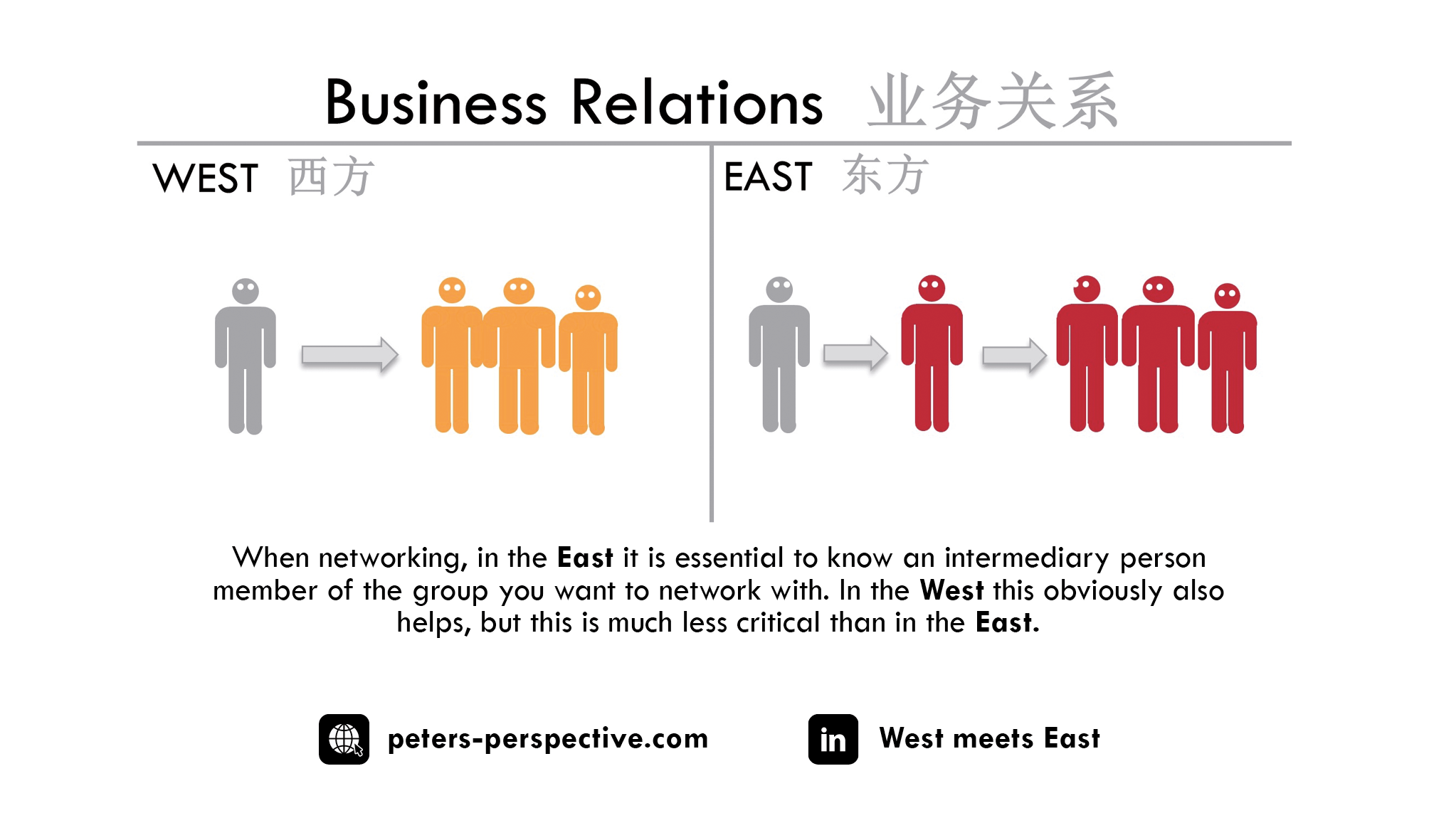

“Yes, David Haasnoot, a master’s student, who did a temperature study for me to create an image of climate change. The last thing I did was add a chapter on food related issues, and had the help of students from Wageningen University & Research. For the rest, I had a lot of phone calls and video discussions with all sorts of people. One of them was Raoul, who made the infographics. Others included Nout Wellink, who was the regulatory supervisor in the Board of the Bank of China, and Frans-Paul van der Putten, a China researcher. My daughter Michelle produced a marketing plan and read everything I wrote. I created a LinkedIn post in which I named everyone.”

You write that your book is targeted at millennials and Gen Z. Why these age groups?

“Because they are still really open for how the world is changing and are interested in others. I hope that it will help people in their twenties and thirties in both the East and the West to understand that we can learn a lot from each other. The overriding long-term vision in countries like China is something the West could learn. I see less openness and curiosity in my generation, generation X. My age peers are mostly looking forward to their pensions and taking things easy. One good thing is that the millennials and Gen Z are or will be the policymakers of the future. Hopefully these generations will also ensure that there are more engineers in politics and policymaking. I think this would help the Netherlands enormously.”

- Order West meets East here.

- Peter Gill has made a playlist (Spotify) and a detailed list of sources that is available through a QR code in the book.

- Also read the series of investigative articles on collaborations between TU Delft and Chinese universities affiliated with the military, which earned Delta a nomination in 2022 for the Tegel, the most important awards for journalists in the Netherlands.

Peter Gill has been a policy advisor on China at TU Delft since 2019. In that capacity he developed, among other things, the Partnering Tools, a tool for scientists to determine whether and how to enter into a collaboration with an international colleague. Before coming to TU, he worked at a variety of companies in the Netherlands, China and Taiwan During his Master’s degree in Mechanical Engineering at TU Delft in the 1990s, he studied Sinology at Leiden University; after studying in Delft, he obtained his Bachelor’s degree in Business Economics.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

a.m.debruijn@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.