The first snow of the year has fallen. Is that early, or late? What do we actually know about snow? The KNMI (Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute) longs for new data on snowflakes. And that is exactly what researcher Nina Maherndl will deliver.

No two snowflakes are alike. (Photo collage: Nina Maherndl)

Nina Maherndl (Geoscience & Remote Sensing) is wearing black gloves. This enables her to see each individual snowflake that falls clearly. The shape of the flakes gives an idea of the conditions in the clouds, for example the temperature. “At -15 degrees Celsius you get very beautiful, regular ice crystals, just like you would draw them. At -5 degrees you get small needles. And if you see small droplets that have frozen on the snowflake, it means that it is rime ice. We then know that small, super cooled droplets have collided with the flake in the cloud. That makes the snowflake more compact and heavy, which means that the amount of snow that can fall is higher.”

It’s bizarre to imagine, as you plow through a snowstorm, that you would capture each flake individually. And yet that is exactly what Maherndl intends to do. Just with her naked eyes looking at her gloves, she can already go some way in interpreting the events. But to do the real work she uses two cameras that record the individually falling flakes and their paths on two sides. Tracking the movements of small particles is done quite often at TU Delft, for example when researching fish. But it is harder following snowflakes, that vary in number and shape, than tracking a school of fish in an aquarium.

Complicated clouds

What makes research on falling snow so important? “At the moment, climate change is one of the biggest problems and clouds are hard for climate models. Some models say that clouds help cool down regions, while others say that they warm them.” According to Maherndl, clouds are complicated to include in the models, and clouds with ice are even more difficult than clouds with droplets of water. “I want to know how ice crystals grow, interact and, if they are big enough, fall as snowflakes. Or, if it is warm enough, fall as rain. I want to better understand what happens in clouds so that we can create better climate models. Snow is one of the missing pieces.”

‘I want to better understand what happens in clouds so that we can create better climate models. Snow is one of the missing pieces’

Improving climate models sounds like a useful goal, but what are the unknown factors regarding snowfall? “There is still much that is not known about the behaviour of falling snow. For example, some models assume that snowflakes always fall at the same speed. I’m going to try to establish a connection between the movement of the snowflake, how it is oriented, and how fast it falls. I hope to link that to the properties of the cloud itself. That could make the models a little more realistic, which could improve long-term climate forecasts.”

Visual measure

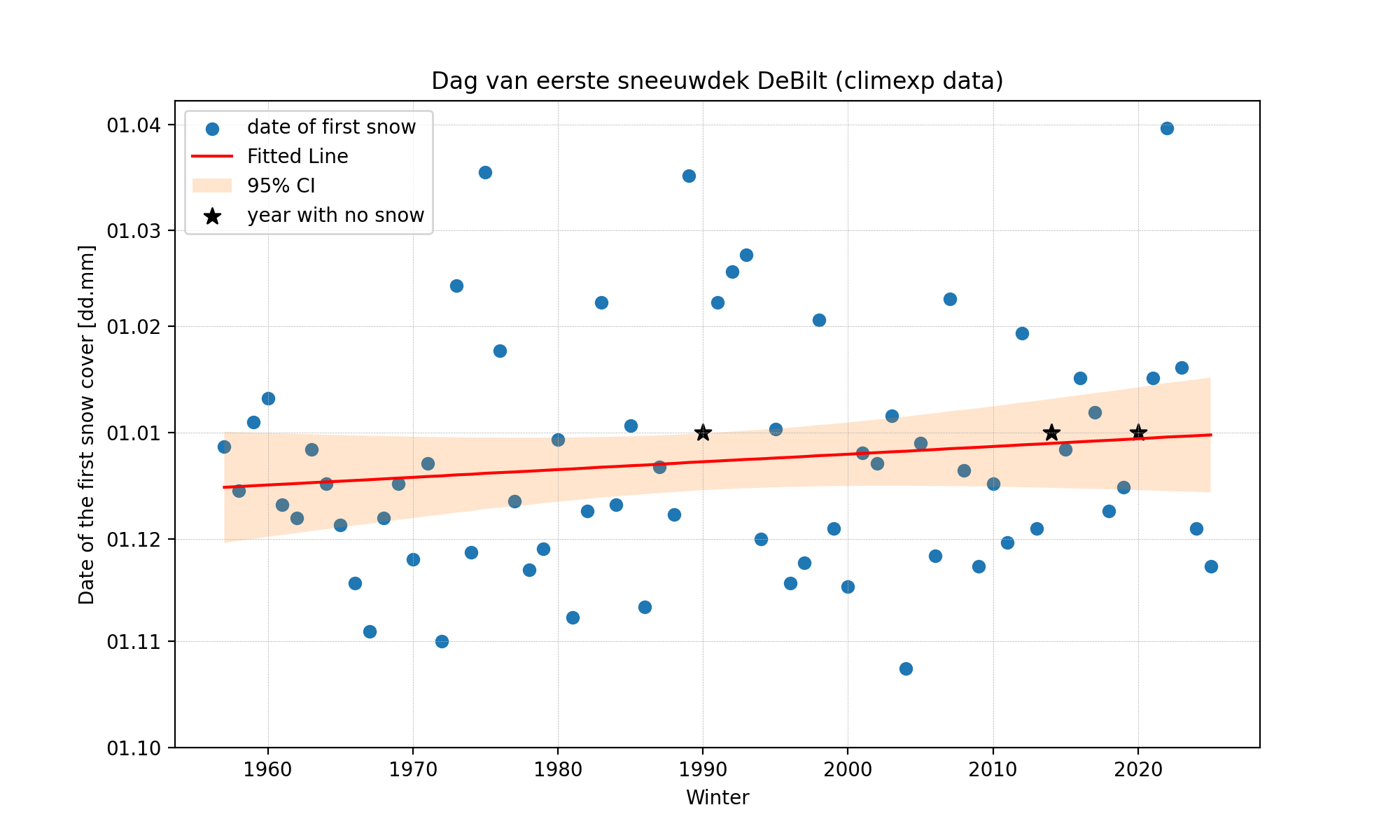

Jules Beersma of the KNMI agrees that snow is hard to express in a model. When answering the question of whether we are early or late with the first snowflake this year, he and his colleague Hylke de Vries dive into the historic data for Delta. There is no data about the first official snowflake of the year. “Snow – either snowfall or flakes – is a tricky weather parameter for several reasons,” Beersma explains. “Snow is a visual measure. We have no instruments to measure snow. We use precipitation meters which are rain meters in which the snow melts. On top of that, there are also several varieties of wet snow – that rarely remains for long – and ‘dry’ snow that remains longer.”

So for information about the first snowflake, we cannot turn to the KNMI. Beersma explains that “Not every snowflake that falls is included in the KNMI archives.” What the KNMI does record is the snow cover. These are daily measurements of the thickness of the snow cover, measured at 08:00. But even then, there may be snow in one place and not in another. De Vries adds that this is only a snapshot of a situation and only of snow that has remained on the ground, and not of sleet or melted snow. Further, the snow cover is not measured every year.

Analyses of snow and new data are thus very much welcome at the KNMI. And Maherndl is working hard on this. Her snow measuring system is almost three metres wide and has two perpendicular cameras. The trick is that they do not get covered in snow or disrupt the path of the falling snowflakes. The system can take 200 photos a second.

Raindrops

Using this set-up, Maherndl can not only measure snow, but rain too. “You may expect that raindrops have a typical droplet shape, but in reality, they are more compressed so are more oval, shaped like a hamburger. Raindrops can oscillate, which we may be possible to see using this equipment.” But she is more fascinated by snow than by rain. “I love snow. People often say that each snowflake is unique. I never really looked into this before my doctoral research, but now I think that they could be right.”

That the researcher will miss the first snowflakes of this year is no problem. “Once the equipment is ready, we will first calibrate it using fake snowflakes punched out of foil. We don’t need to wait for snow in the Netherlands,” she adds, laughing.

The path of falling snowflakes photographed from two sides. Photos: Nina Maherndl, adapted from Maahn et al. (2024)

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

E.Heinsman@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.