News from China: an experimental molten salt reactor is said to have run on thorium for the first time. This type of technology is also being developed in Delft. Last week, an agreement was presented for the construction of Europe’s first pilot plant. Nuclear physicist Martin Rohde: “The thorium reactor is the holy grail.”

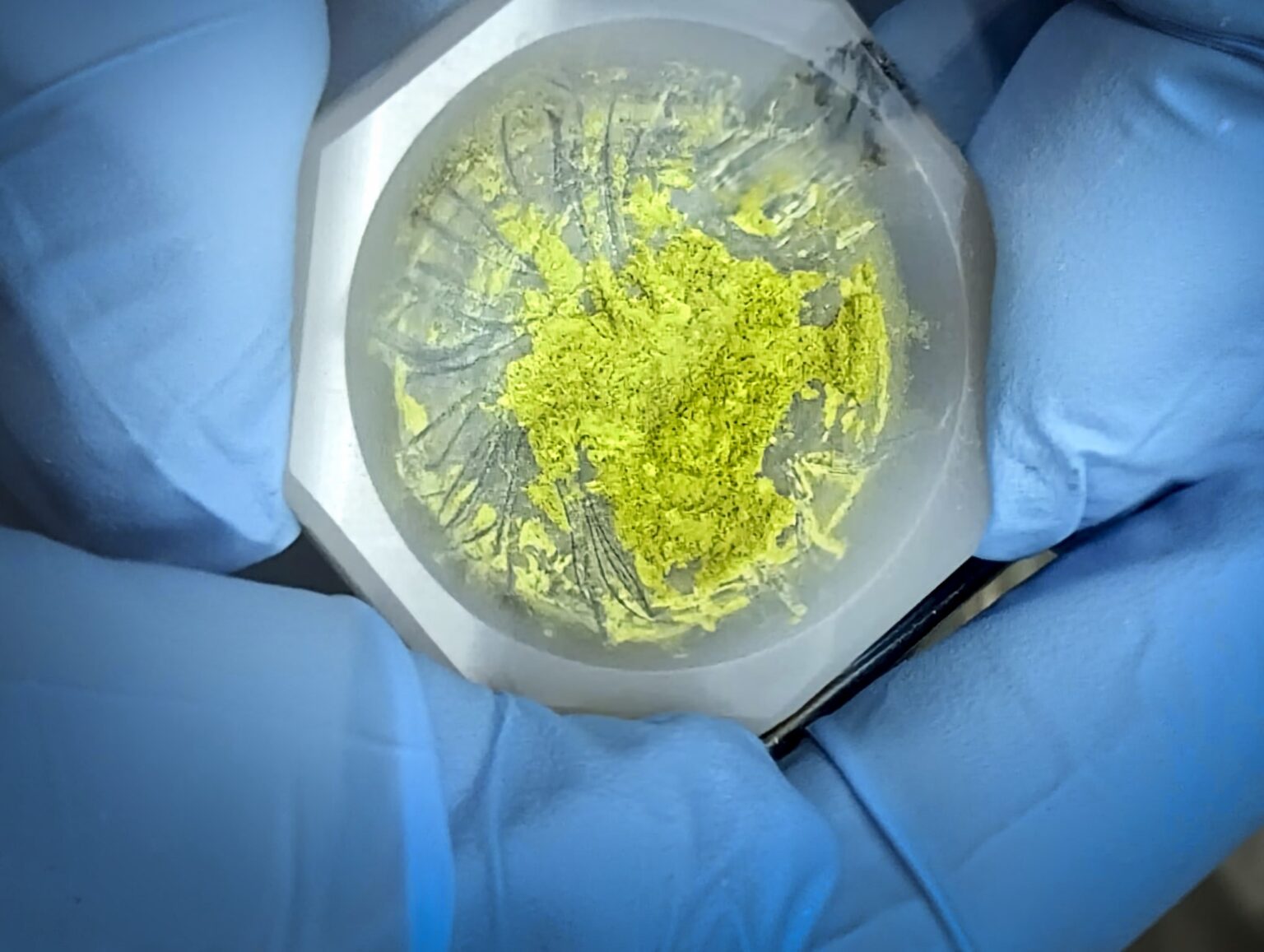

Uranium chloride, the fuel produced from thorium chloride in the thorium MSR. (Photo: Nick ter Veer, Radiation Science & Technology, AS)

Politicians see thorium as a future energy source, and the business community is also becoming more interested. Why all this interest in thorium? The first experiments with a molten salt reactor, and the ideas for using thorium as a medium, date back to the 1960s. If this would become the new way of generating energy, how long will it take before it is available? A lesson on thorium by Martin Rohde (Radiation, Science and Technology department, TNW).

What is thorium?

“Thorium is found all over the world, in some places more than others. In Norway—where the element was discovered—there is more of it in the ground than in the Netherlands. It is named after the god Thor. In many other processes, for example when extracting rare metals, thorium is released that we currently have no use for. It used to be used for camping gas stoves, but that’s about it. There are mountains of thorium waste waiting to be used. It is a super stable element. Almost all thorium found in the earth’s crust is older than the solar system. If you dig up a shovel full of soil anywhere on earth and use the thorium in it to generate energy, it is equivalent to the energy produced by 60 liters of gasoline. So it is not a critical raw material. The fact that it is so abundant worldwide takes some of the pressure off the political situation.”

What is the difference between a molten salt reactor that runs on thorium and a conventional nuclear power plant?

“There are many differences, but the most important one is the fuel. A conventional reactor runs on uranium, which is highly fissile. When you fire a neutron at it, it splits and you get new neutrons. This causes a chain reaction, which we keep under control in the nuclear reactor. During fission, the particles jump from their place at enormous speed and cause vibrations. Harder vibrations mean a higher temperature, so the material becomes hotter. You can dissipate that heat and convert it into electricity.

‘The biggest advantage is that the waste from a thorium reactor needs to be stored for much less time’

Uranium occurs in nature in two forms: 235 and 238. Uranium-238 is a heavy isotope. When it absorbs extra neutrons, elements are formed that do not exist in nature at all, such as plutonium, americium, curium, and neptunium. Some of these are radiotoxic for a long time which means nuclear waste that must be stored for a long time.”

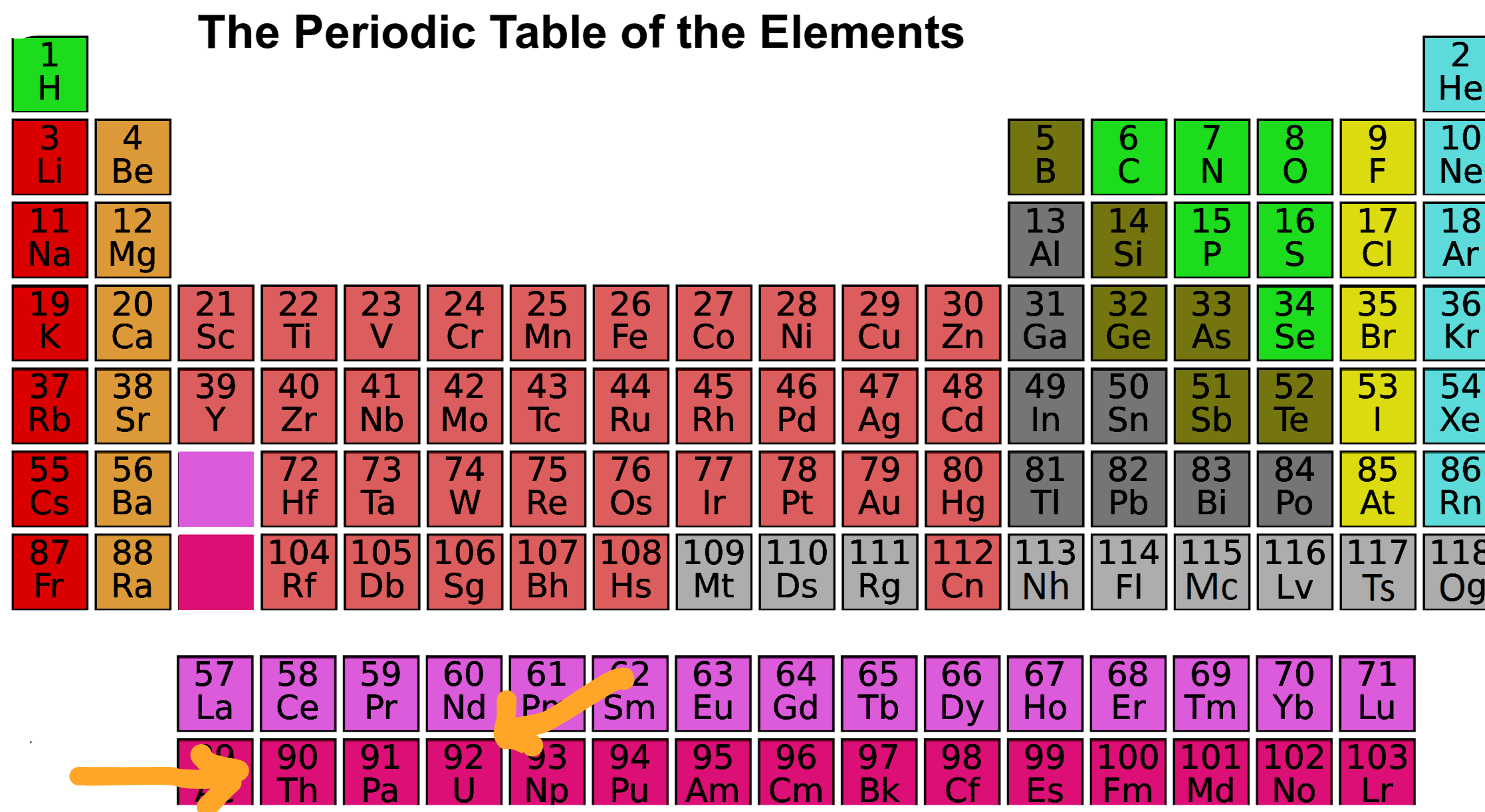

Rohde shows an image of the periodic table. “Thorium-232 is not fissile in itself, but it is close to uranium. If you bombard thorium with a neutron, you get the rather unstable thorium-233, which decays into uranium-233 in two steps. Uranium-233 is a dream fuel: it generates a little more neutrons than uranium-235 and is highly fissile. Because thorium-232 is six steps lower than the uranium-238 in a conventional nuclear reactor, the chance of ending up with those long-lived isotopes is much smaller. The waste from a molten salt reactor needs to be stored for about 300 years. That’s quite different from the 250,000 years required for a conventional nuclear reactor. In my opinion, this is the biggest advantage of a molten salt reactor. The thorium reactor is the holy grail.”

What is the role of that molten salt?

“In a conventional reactor, you need one neutron for fission, but with thorium it takes two steps, so you need two neutrons. Because you ultimately want to get more energy out of it than you put in, you have to be very economical with your neutrons.”

“A conventional reactor contains a lot of steel, and a lot of water flows through it, and this is where some of the neutrons get captured. What you want to build, is a reactor that contains as little material as possible in which neutrons can disappear. That leads you to a large container of salt. The fissile material is evenly dissolved in it. Inside that container of salt, the uranium begins to fission, causing the temperature to rise to 700 degrees. That hot molten salt then flows through a heat exchanger to dissipate the heat. After that, the process starts all over again. This ensures that as many neutrons as possible remain, to keep the two-stage rocket going, with far fewer neutrons disappearing.”

Boiling hot molten salt—won’t that corrode the reactor?

“The salt is hot and corrosive. So we have to look for materials that can survive this for forty, maybe even sixty years. In America, such a molten salt reactor has been running for some time, but never for sixty years. Here and in mechanical engineering, research is being conducted in which materials are exposed to hot salt, and we extrapolate this to longer time scales. Finding suitable materials to build the reactor is one of the biggest challenges.”

Now for the news about the Chinese thorium reactor. It was called a ‘world first’. How far along are they?

“I don’t want to downplay it; it’s an important step. They have succeeded in getting the reactor to produce a small amount of uranium-233 and reuse it. But the goal is to have a reactor run entirely on thorium, and that is certainly not the case here yet. I’m not saying it’s not a milestone, but I think the marketing has also worked well.”

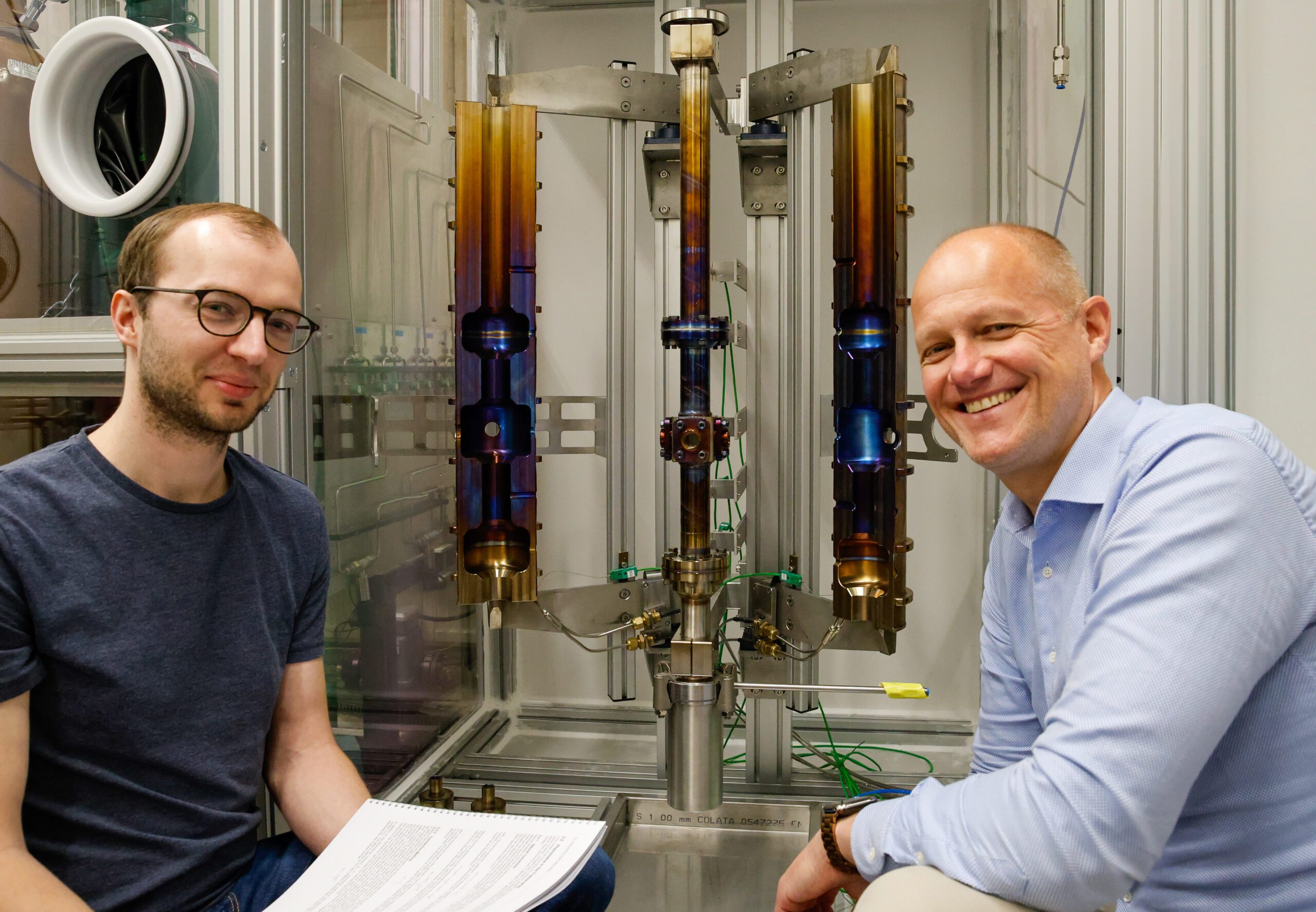

Last week, during the ‘Made for nuclear event’ in Hilversum , an ambition agreement was presented for the realization of the first molten salt reactor demonstrator for Europe: Thorizon Pioneer. This is a collaboration between many parties, led by the start-up Thorizon, with Delft University of Technology as a research partner. What does this collaboration look like and, more importantly, how long will it take before energy from a molten salt reactor reaches our power outlets?

“Technically, it’s all possible. Now it’s mainly a matter of regulations, licenses, the question of where to build, and extensive testing before you can actually start building. The entire fuel cycle, from extracting thorium from ore, to processing and dealing with the final waste, still needs to be developed. And very importantly: the financing.

We consult regularly with Thorizon and collaborate on various projects related to molten salt reactor technology. It is very special that we are doing this in collaboration with a Dutch company. I expect that we will have a fully functioning molten salt reactor between 2040 and 2050. I am a little more cautious about 2030, which some people are mentioning.”

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

E.Heinsman@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.