New ideas often challenge established concepts, sometimes even those invisible to us. Filippo Maria Doria’s award-winning architectural concept – A Design for a library for the blind sighted in Parco di Villa Borghese alongside Rome’s central library – challenges the hegemony of eyesight in architecture.

The concept recently won first place at the ArchiPrix Netherlands with Recording and Projecting Architecture. The best graduation projects by students studying architecture, urban planning and landscape architecture across the Netherlands are chosen by their faculties and nominated for the competition.

In its most simplistic explanation, Doria’s design explores space from the perspective of the visually impaired. “The digital world, like most other spaces in our physical reality, is predominantly visual. When online, someone visually impaired only has access to the text and not the environment the graphics create.”

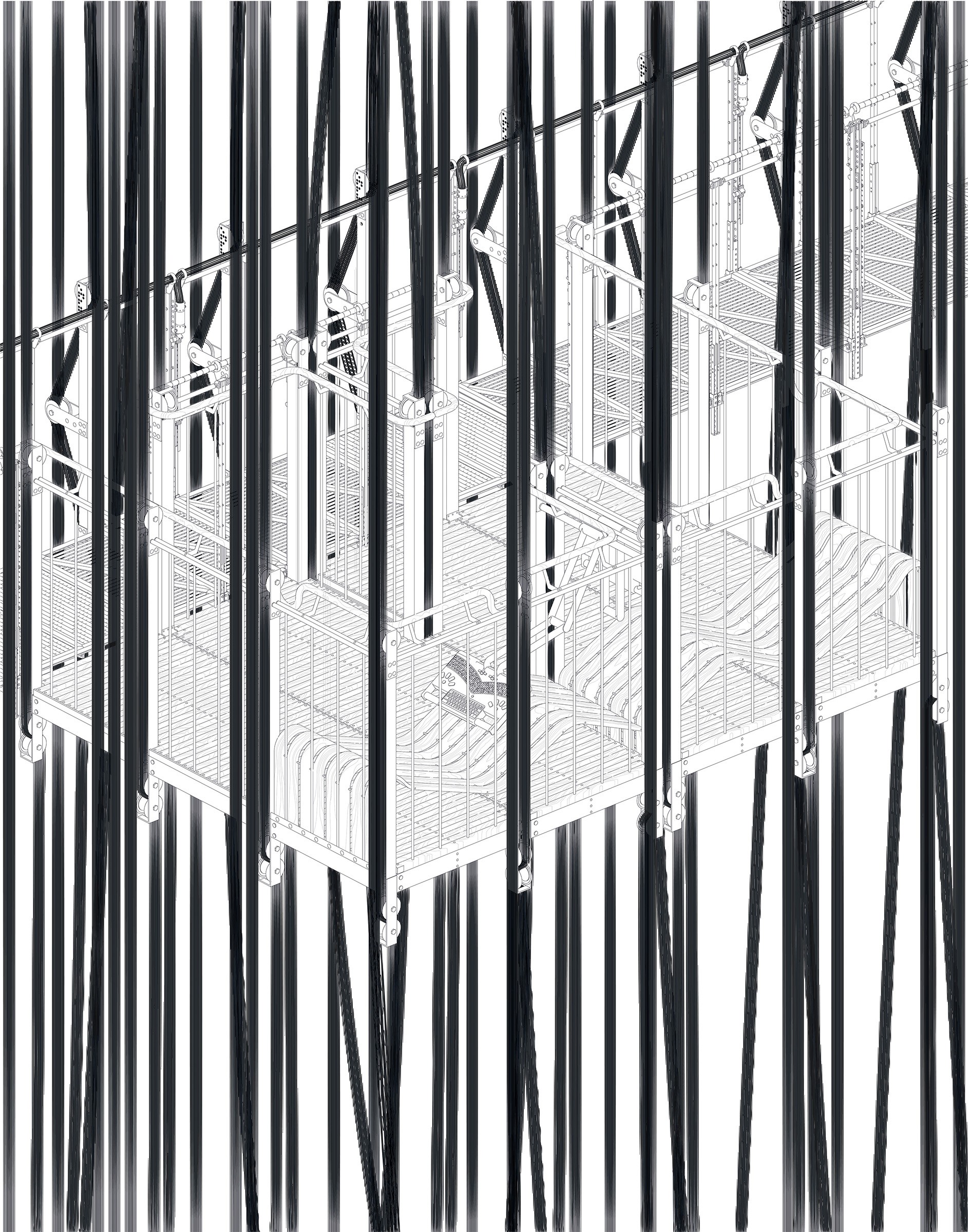

Within this library, once a reader chooses the areas/categories of books they would like to read, cables of digital data rearrange themselves to form a reading-room full of all related books on that topic. Another interesting innovation are seat-beds, so readers don’t need to be seated at a desk to access the books. “All our architecture, art, everything is done to accommodate the line of sight. Someone visually impaired wouldn’t need a posture that aligns the book with the axis of the eyes, instead some other position might be more comfortable…”

The idea for the digital library came on a two-week exploration of Rome as part of the master’s at TU Delft. During that time, students were required to map a district of Rome that would inspire their projects in some way. Doria chose the district of Tuscolano II. “It’s a significant area in the history of Rome and was part of the new image the city shifted towards after World War II,” he says. This led to an exploration of how architecture plays into the narrative of politics, and the gap between reality and representation therein. A gap that becomes manifold for someone who is denied access to that representation altogether.

Doria believes that even the notion of vision here is also open to interpretation. “Blindness is also metaphorical here. I think architecture is not so scientific that a design can have only one right meaning. If you clearly state just one interpretation, you close all others instead of leaving it open-ended.”

Doria, who is now doing a PhD at TU Delft, is pragmatic about the concept. “The project will not work in economic reality.” It is, however, a starting point for a discussion on how drawing, architectural or otherwise, help you interpret reality. Something he hopes to explore further in his PhD in the coming years.

Comments are closed.