Lazing on the beach and drinks in the sun? Twenty Master’s students from TU Delft chose an unusual destination this summer. They travelled to South-east Asia to carry out fieldwork for Dutch companies. “This is the crowning glory of my student days.”

Many companies want to get to know talented students, raise their profile at TU Delft as a potential employer, and obtain a report with recommendations on how to better organise their business activities in a distant development country, and are willing to invest time and money to achieve this. This desire has enabled the International Research Projects Delft foundation, which was founded in 2008, to send 20 ambitious students a year out into the world in groups of four, to carry out fieldwork in emerging markets.

This summer students carried out research for Heineken, Philips, Allseas, Petrofac and Fugro in 10 countries in South-east Asia. They were involved in a wide variety of projects, ranging from beer brewing in Papua New Guinea to manufacturing cheap irons in Indonesia. A project like this is a valuable addition to any CV. You join other students in a multidisciplinary team working on a large project, getting to know a company from the inside out and speak with CEOs, CFOs and chief engineers and being exposed to a totally different culture.

Drinking tea in Indonesia

Soil and ground researcher Fugro is facing strong competition in South-east Asia. Research equipment is becoming increasingly less expensive, which means more and more companies are entering the market. Bram Mulder, who is studying flight performance & propulsion (Aerospace Engineering), and his three teammates were commissioned by Fugro to analyse the local market for soil and ground research by conducting interviews with rival companies and with Fugro’s clients. “We were amazed at the warm welcome we received from the competition. The Fugro management in Singapore knew the etiquette, and a representative from Fugro Singapore flew out with us to Jakarta to introduce us to one of their competitors. He stayed for 10 minutes to show his respect and then flew straight back to Singapore. Personal contact is very important in South-east Asia. It would be a rare thing for this to happen in the Netherlands. When dealing with your client it is also important to show that nothing is more important than your relationship with him So if he calls to ask you a question, you shouldn’t give the answer on the phone but go and have tea with him. You have to drop everything you’re doing to attend to your client.” Mulder sees the project as a good conclusion of his time as a student. “This is the crowning glory of my student days. It’s great to work together as a team, particularly learning how to put your ‘soft skills’ to good use. And you learn how to demarcate and converge the problem, after which you can expand it again later. I am really happy that I was able to use my skills in this cool company.”

Talking to the village chief under the mango tree.

Cassava root? That was completely new to them. Two months after the start of their project, Elise de Reus and her companions had dug the roots themselves, set up a logistical network to collect the harvest and learned how to make cassava beer. This was all part of their project for Heineken subsidiary South Pacific Brewery in Papua New Guinea. “For reasons of sustainability, this company is looking to replace part of the malt it uses in beer making, which is imported from Australia, with cassava grown by local, small-scale farmers”, explains De Reus, who is studying for a Master’s in biochemical engineering. “You can replace up to 10% of the malt without changing the flavour. But how do you make sure the brewery has a sufficient supply of cassava? At the moment the farmers are not producing enough. Besides this, Papua New Guinea is still a developing country, mountainous and heavily forested, with roads that are often impassible. Fortunately we came across a poultry company that buys most of its chickens from small-scale farmers. This company already has an entire network in place complete with trucks. So our suggestion was to get these communities to also supply cassava.” The students followed the chicken trail and visited the villagers to discuss the idea. De village chief werd er dan telkens bij gehaald. Maar hij niet alleen, het hele dorp verzamelt zich rondom de tafel onder de mangoboom.”“The typical Papua New Guinean system of ‘wantok’ (one talk), in which communities are defined according to language groups, leads to strong relationships within communities. We had to make a close study of this cultural context for our project. The wantok system can sometimes complicate matters when doing business because of the many sensitive issues between the clans. The advantage is that news travels through the wantok system like wildfire. I really think that it’s going to work, and there is a great willingness on the part of the brewery too. It really is a great project.”

Giggling in the iron factory

It didn’t take long for the giggling to start. The female factory workers on the assembly line making irons had seen old white men visit from time to time, as well as people from India, and men from Singapore. But three young white men and a young white woman walking through the factory and asking all kinds of questions, that was something new. Maurits van der Donk, a systems engineering student, has to laugh when he thinks back on his team’s visit to Philips’ electric iron factory on the Indonesian island of Batam. “We met an awful lot of people, and were even invited to come and eat with them.” The students were tasked with calculating the production cost for the cheapest iron made by Philips in the world’s largest iron factory. “And then we had to think of ways to make it even cheaper. There are different machines for the different models, and people work on different types. Then there is the water and energy consumption. How do you determine which costs are incurred for a single model of iron? We spent a lot of time standing next to the production line, observing things. Before leaving the Netherlands we visited Philips’ electric shaver factory in Drachten, we thought our background knowledge from Drachten would help us make improvements here. But we couldn’t believe what we saw! Every department has something that the other needs. They communicate using paper notes, which works incredibly efficiently. There’s a continuous flow of parts through the factory. Still, we were able to make a few suggestions to reduce costs. For example, fitting a slightly more expensive thermostat in the iron enables you to make the iron itself cheaper, as the expensive thermostat is more accurate so you can get away with using a thinner aluminium sole plate. I never thought I would become an electric iron expert. At first I thought ‘What am I doing here?’ Normally I’m involved in far more abstract concepts. But it’s very good to work with a team in a totally alien environment and build up a working knowledge of something you know absolutely nothing about.”

Gas to liquid; making the connection

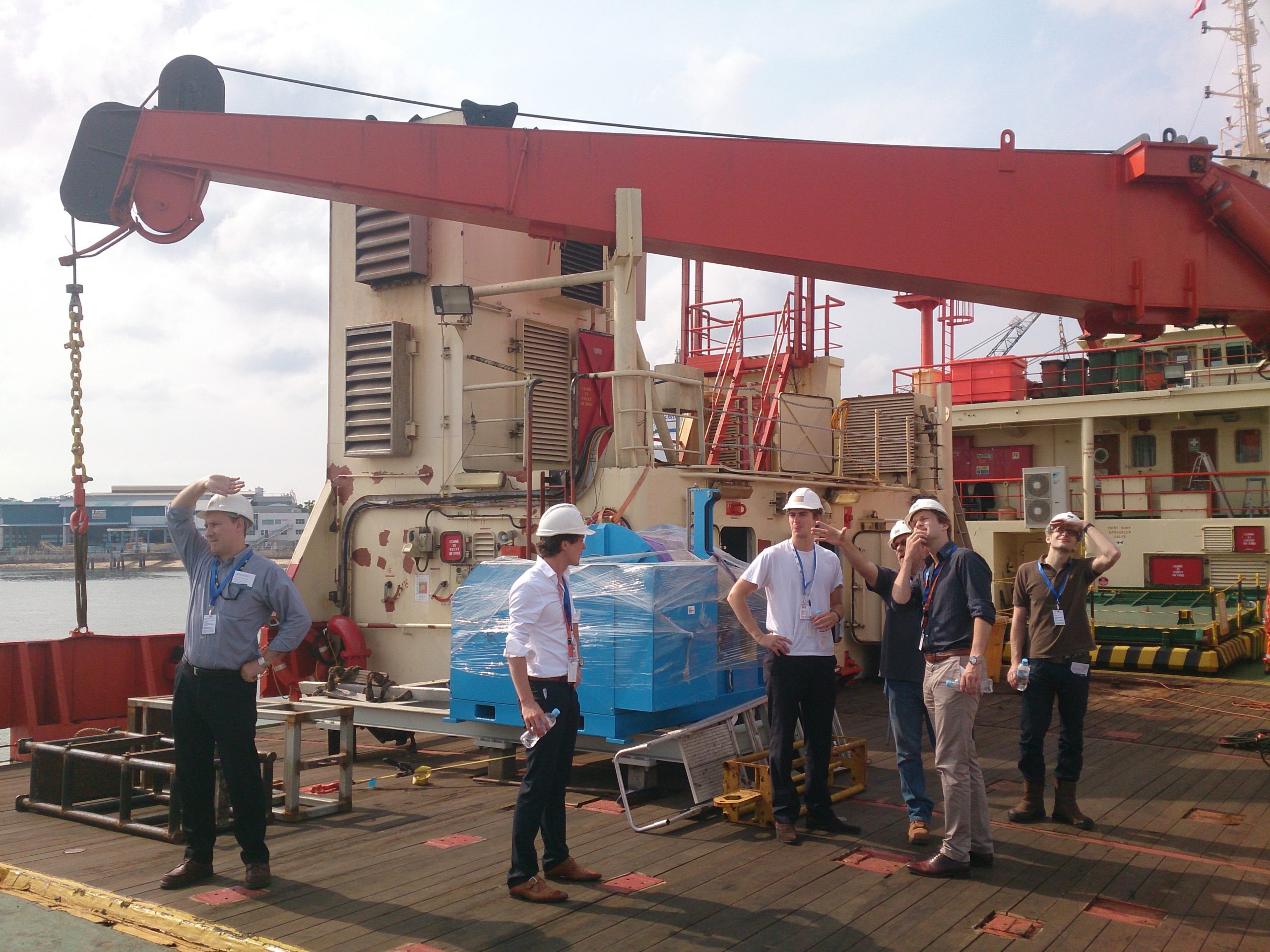

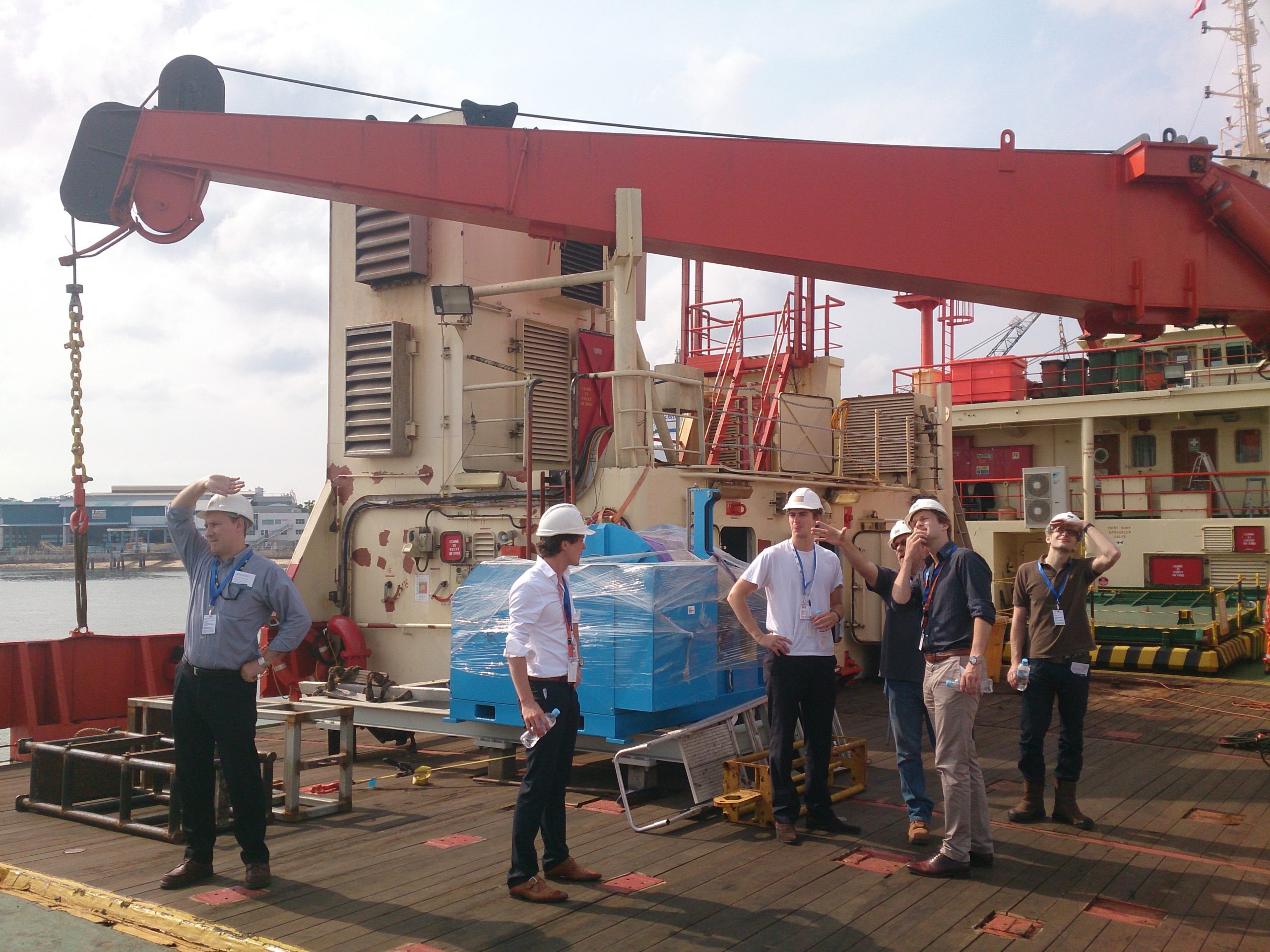

“To start with, the chief operating officer from Singapore visited Delft, accompanied by one of the chief engineers from London. After the initial brainstorming session, we really got down to work”, explains Gilles Louwerens, speaking on the phone from Singapore. The student in petroleum engineering & geosciences is in Singapore as part of a team with three other students, studying a technique for converting natural gas into oil. They are doing this for Petrofac, a service company in the oil and gas sector. “The idea is to use this technology on ships that treat and store oil and gas, known as FPSO (Floating Production, Storage and Offloading)vessels. The problem faced by these vessels – which are often converted oil tankers – is that a lot of gas is also brought to the surface during the oil extraction process. As there are no gas pipelines, they flare the raw natural gas. Of course they could pump it back into the ground, but that costs money. The amount of gas flared in this way is enormous, amounting to thirty percent of the annual gas consumption in all of Europe. Gas-to-liquid technology could provide an answer to this problem, although this has never before been attempted in an offshore setting. We are evaluating the risks involved – a completely new area for me.”

Studying welds in Asia

With visits to China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Singapore and Indonesia, Nicole Mooibroek has certainly been on the move. `It was a constant round of unpacking, packing up and moving on again. We were living out of our suitcases`, explains the construction management and engineering student. She took a crash course in offshore engineering at TU Delft before setting off with her team-mates on a two-month journey around South-east Asia, mapping out suitable shipyards where Allseas ships could put in for repairs and/or maintenance. Allseas is a company involved in laying offshore pipelines. “In the beginning we thought it would just be a question of ticking the boxes on our list: Is the yard big enough to take the Allseas ships? Do they have the right equipment, knowledge and facilities? But it turned out to be a far more complex task. We had to verify every detail. The shipyards are so keen to have Allseas as a customer, that they often paint a rosier picture of their capabilities than is really the case. We even found ourselves inspecting welds.”

Comments are closed.