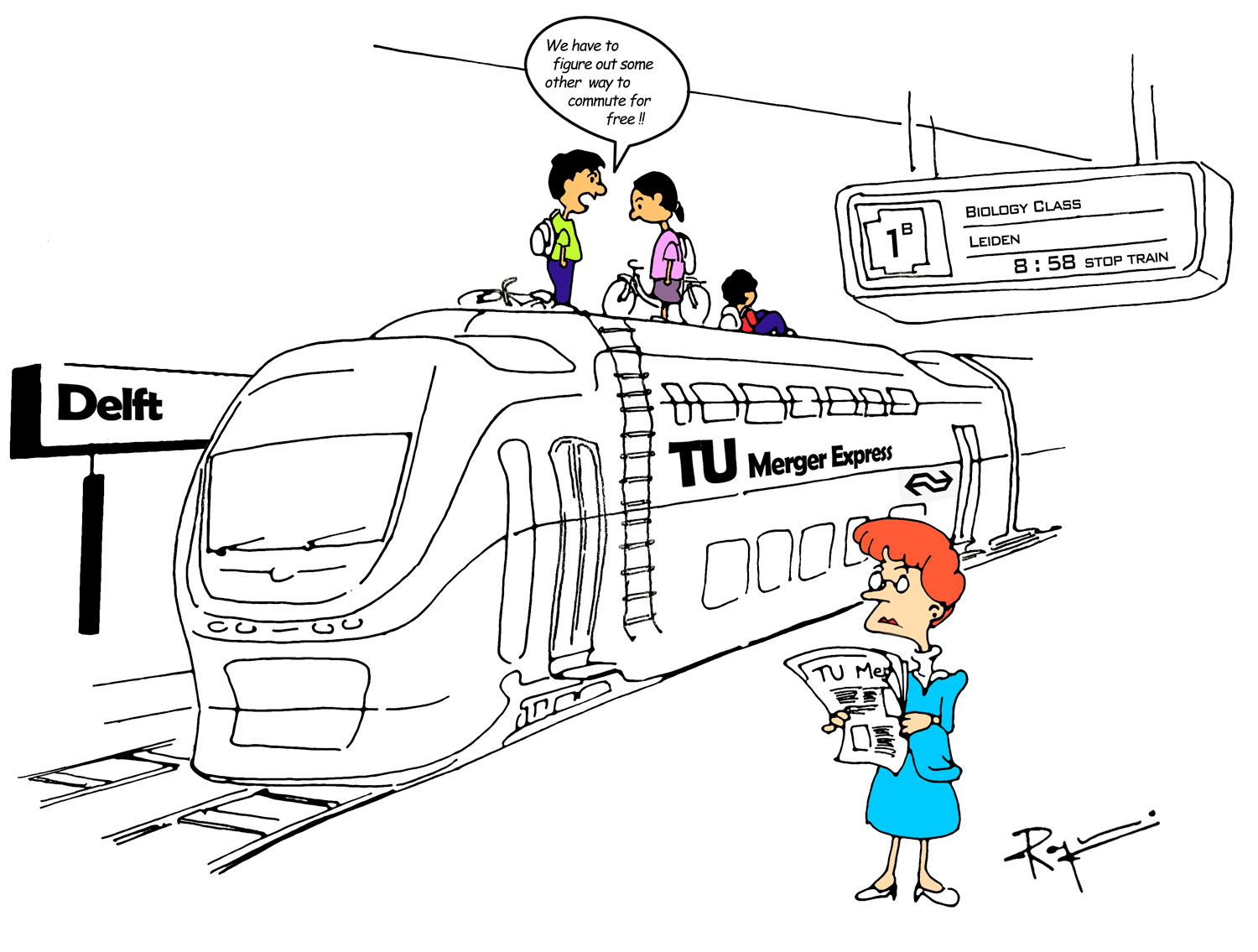

Despite a recent Delta survey that revealed that a majority of TU Delft students oppose the planned merger of TU Delft with the universities of Leiden and Rotterdam, such a merger seems likely in the near future.

But what would a merger mean for TU Delft’s international students, many of whom specifically chose to study here because of TU Delft’s good reputation and name-recognition back home and among the international scientific community? And what additional costs should TU international students expect to incur as a result of a merger? Unlike TU Delft’s

Dutch students, for example, international students are not given OV cards, allowing for free travel on Dutch trains. Consequently, having to commute from Delft to Leiden or Rotterdam by train to attend certain courses – as the merger plan envisions – would be a major additional expense for TU Delft’s already cash-strapped internationals.

Suppose you manufacture smartphones and want to incorporate external parts, like a gyroscope or a beamer chip. With current technology, the common way of placing the parts on exactly the right spot is to use a precise but slow pick and place robot. In his PhD research at the faculty of Mechanical, Maritime and Materials Engineering, Dr Iwan Kurniawan developed an alternative two-step micro positioning technique. A quick and coarse positioning of the millimetre-sized chips onto a silicon wafer is followed by a very accurate self-positioning. Shaking the wafer for about 30 seconds suffices for the chips, driven by electrostatic attraction, to fit into their slots.

Kurniawan used a silicon wafer as a base. The places where the chips should align are covered by an insulating layer of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Placed under a corona charging device, the SiO2 patches can be charged to surface potentials of hundreds of Volts. The small chips are given an opposite charge. Miniscule pegs are fabricated on the chips to prevent contact between the opposite charges as the small chips bump around on the shaking wafer. When accidentally the pegs align perfectly to the funnel-shaped slots on the wafer, the chip slips into place like a key in a lock with micrometer precision. The success rate is 100 percent, Kurniawan says.

Although the project was paid for by MicroNed, a programme aimed at developing technology for industry, manufacturers have shown little interest thus far. Kuriawan thinks the uncertainty in processing time is holding manufacturers back: “Because the alignment process is stochastic, the process duration may vary from chip to chip.” Never-theless Kurniawan stresses that his batch processing is more appealing than the present piece-by-piece approach.

Iwan Kurniawan, ‘Dry self-aligment for discrete components’, 3 December 2010, PhD supervisor Prof. Urs Staufer

Comments are closed.