Universities and universities of applied sciences are launching more new programmes than they are discontinuing, says Minister Eppo Bruins. It’s one of his arguments for forcing them into joint discussions. But is his count accurate?

Students for academic or applied sciences in the Netherlands can choose from nearly 2,500 courses. (Photo: Thijs van Reeuwijk)

‘There needs to be more collaboration between educational institutions and more national coordination on the range of degree programmes’, states the first sentence of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science’s (OCW) news release about a policy letter from Minister Bruins in which he discusses the future of vocational and higher education.

His stance is linked to the expected decline in student numbers. This is due to demographic shifts in the Netherlands, and the Government’s intention to curb the influx of international students.

Some programmes will disappear, the Minister predicts, but he wants to prevent ‘crucial education for Dutch society being lost’ while ensuring that universities and universities of applied sciences continue to respond ‘to opportunities for the economy and society’.

So what needs to happen? “It’s important that the range of degree programmes develops and adapts to societal changes,” he says. “In recent years, more programmes have been launched than discontinued.”

Fact check

We looked into that claim. While it’s not explicitly stated, the suggestion seems to be that universities and universities of applied sciences do not sufficiently consider public interest and are launching too many degree programmes.

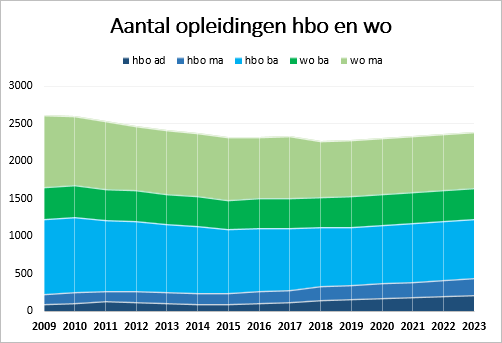

We have data going back to 2009. At that time, there were more programmes than today: 2,600 in total. But the number of programmes declined for years until 2018, after which it started rising again. So is the Minister right? It depends on when he starts counting.

Moreover, the number of academic bachelor’s programmes has remained constant, while the number of vocational bachelor’s and academic master’s programmes has actually decreased. The increase is mainly in the number of vocational master’s programmes and associate degrees (two-year higher professional education programmes positioned between vocational and bachelor’s levels).

The Government has facilitated the expansion of vocational master’s degrees and encouraged the introduction of associate degree programmes. So it’s hardly surprising that more of these programmes have been established. In fact, the Ministry doesn’t expect these types of programmes to shrink.

Bruins’ response

How does Bruins view these figures? “The statement that more programmes have been launched than discontinued refers to the overall range of programmes (vocational, academic, associate degree through to master’s level),” his spokesperson explains. “There are indeed differences between the types of programmes.”

Do these figures indicate an inefficient education system? “No,” the spokesperson replies. “The number of degree programmes alone doesn’t directly reflect the efficiency of the system.”

Is the Minister suggesting that too many associate degree and vocational master’s programmes are being launched? “No,” the spokesperson answers again. “The key message is that the range of programmes must continue adapting to societal needs. But that also means that as student numbers decline, the number of programmes won’t automatically keep growing.”

Disappearing programmes

Right now, the issue isn’t that too many programmes are being created. Instead, some programmes are at risk of disappearing – programmes the Minister would actually prefer to keep, such as those in regions with few students. Various smaller language programmes are also under pressure.

In fact, some of these programmes are already vanishing, and given budget cuts and declining student numbers, this trend is only expected to accelerate in the coming years. So, what can Bruins do? He doesn’t have a bag of money to offer – after all, he’s cutting funding for higher education and research.

That’s why he’s turning to non-financial measures such as setting up a new consultation forum. He is making collaboration between institutions mandatory and is legally enforcing national coordination of degree programmes.

The advantage for the Minister? Soon, all institutions will share the responsibility for closing or maintaining programmes, and he can always point to their collective decision-making. This makes him, or his successor, less politically vulnerable.

HOP, Olmo Linthorst en Bas Belleman

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.