Space system engineers are building the next generation of mini-satellites that can fit into your pocket. Soon they’ll be as common as drones.

TU Delft’s first mini-satellite, the CubeSat Delfi-C3, will celebrate its tenth birthday in space in April next year. “People didn’t think that satellites built with smartphone hardware could survive in space,” exclaims project manager Jasper Bouwmeester, MSc, at the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering. Here, on the eighth floor, researchers and students build their own satellites. They even have a clean room to keep out dust particles.

Jasper Bouwmeester holding a PocketSat. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

Jasper Bouwmeester holding a PocketSat. (Photo: Jos Wassink)After ten years of operation, it appears that standard circuitry is good enough to function in lower earth orbits. Mini-satellites are stationed between 300 and 800 km of altitude and will, over time, burn up in the atmosphere.

Over the last decade, CubeSats have turned into a booming business. The Earth monitoring enterprise Planet.com, for example, launches them by the dozens. Their website states: ‘Planet is designing, building and launching satellites faster than any company or government in history. We use commodity consumer electronics to build highly capable satellites at drastically lower costs.’

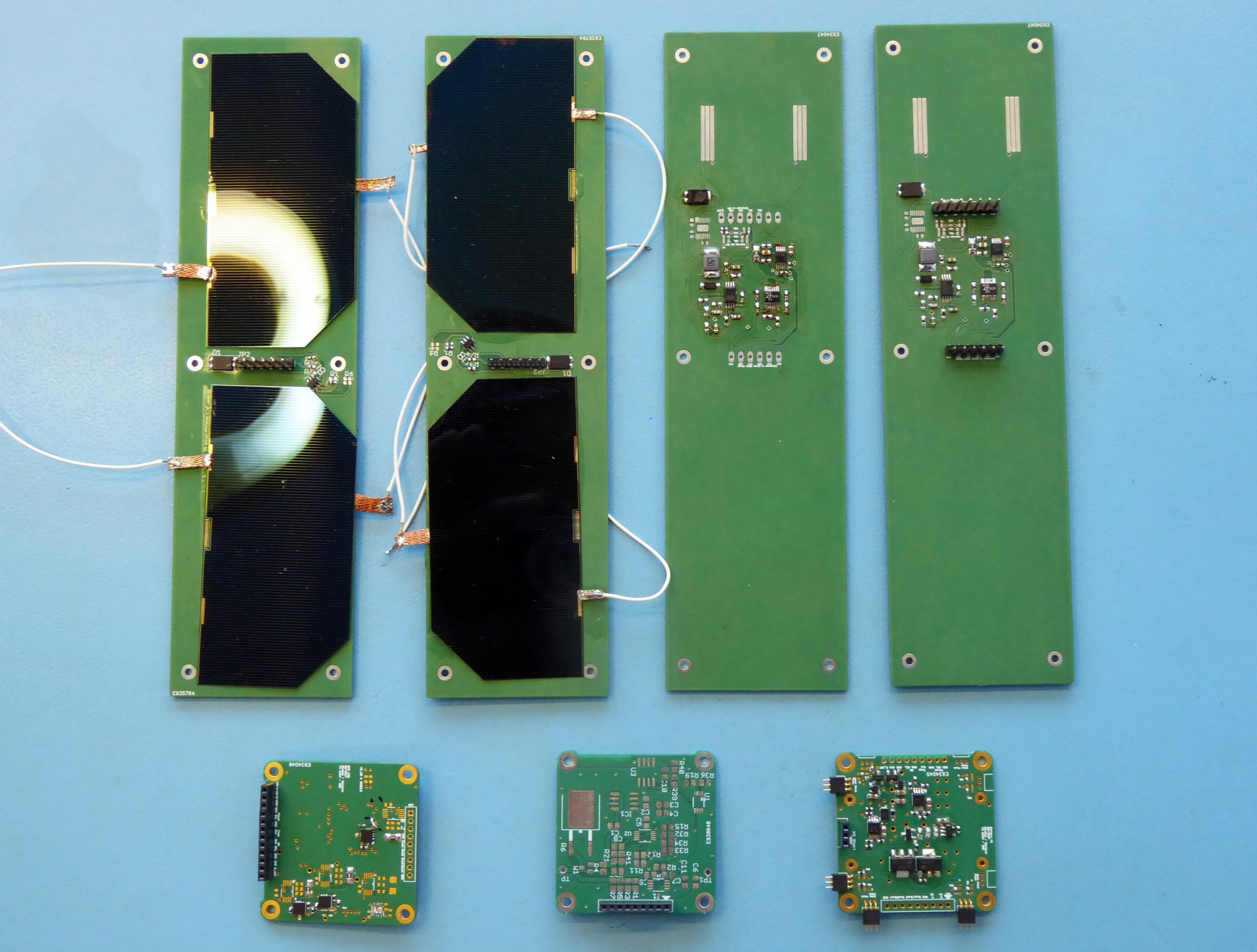

The PocketSat as a construction kit. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

The PocketSat as a construction kit. (Photo: Jos Wassink)And so, academic research is moving on. Researchers are exploring the potential of the next generation of mini-satellites: the PocketSat. It is half the size of a CubeSat in every dimension and about 20% of the mass (0.5 kg).

Besides the use of even more compact electronics and sensors, the next generation also integrates functions that allow a smaller and more compact design. The PocketSat should offer a platform that includes electricity, a computer, a communication unit, and thermal control. The platform supports any sensor or camera of choice, as long as it fits. Additional options include propulsion and attitude control to stabilise the box.

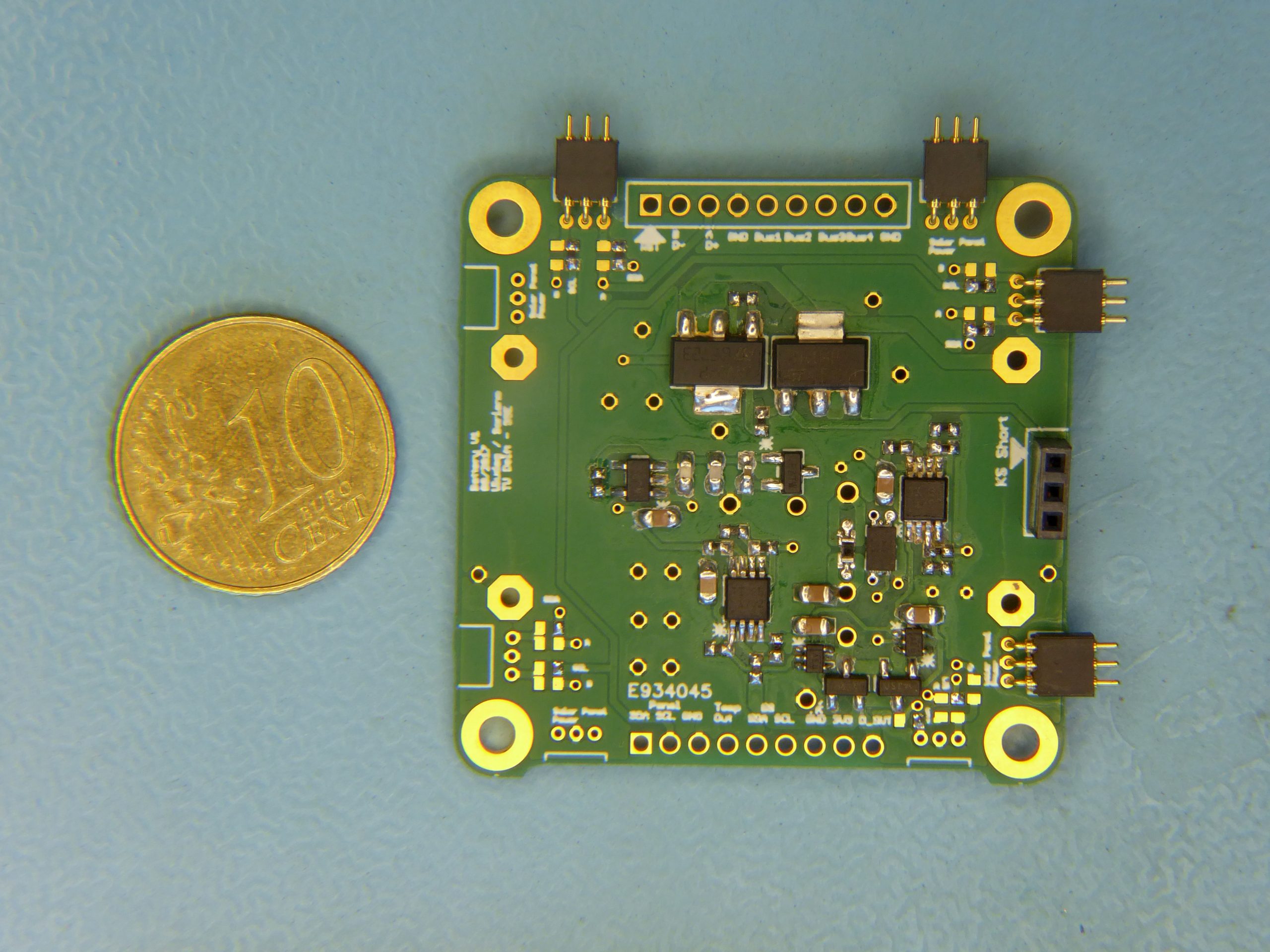

The board computer has shrunk as well.

The board computer has shrunk as well.The current PocketSat is scheduled for launch by the end of 2018. After that, the Space System Engineering group aims to launch an updated version every year.

Their small size and budget allow mini-satellites such as CubeSat and PocketSat to operate in formations or swarms. Spreading the minisats out either enlarges the field of view or increases the frequency with which a particular location on Earth is visited. Or both. People working in agriculture, defence, forestry, infrastructure, and governments are rapidly discovering the benefits of this tailor-made remote sensing.

Spinning up the disk counteracts undesired rotations of a satellite.

Spinning up the disk counteracts undesired rotations of a satellite.Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.