Darwin revolutionized our way of thinking about life by realizing the potential of natural selection through survival of the fittest. Delft biotechnologists believe that the same mechanism can help the biobased economy, by the ‘survival of the fattest’.

Algae are interesting candidates for the large-scale production of biodiesel. Researchers of the department of biotechnology have developed a clever way of finding the fattest and therefore the most suitable examples among all the many species of algae. An article entitled Survival of the Fattest describing their new approach appeared in the online edition of Energy and Environmental Science on October 21 2013.

A major threat to the stable cultivation of oil-producing algae is infection of the relatively fat oil producing algae by other, thinner algae. One option is to use a sealed cultivation system and keep unwanted algae out by means of sterilisation. To do this on a large scale is extremely expensive. The Delft researchers use a completely different approach. They try to select for a particular characteristic and not for a particular species of algae.

“We are unconcerned whether species A or species B is used in our system, as long as they have the characteristic ‘fat’. So all algae are welcome in our system”, says the first author of the article, PhD student Peter Mooij, in a TU press release.

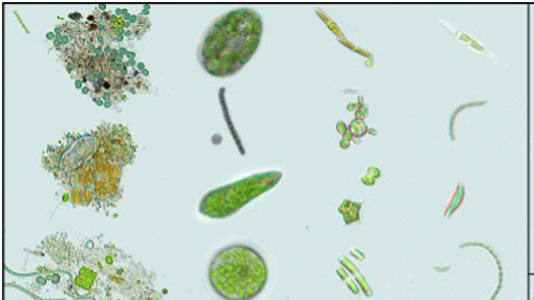

Approximately 50 microalgae strains are used for the majority of microalgae research, while evolution has resulted in 40 thousand identified and a multitude of unidentified strains. So statistically speaking it is likely that many more suitable candidates are present in nature, or so the researchers argue. Put in this perspective the inevitable contamination by invading species becomes of value instead of a threat to the production process.

To filter out the most promising algae, Mooij used a feat-famine regime. Algae produce oil to store carbon and energy. Energy and carbon are useful to them during the long sunless periods or if it is cold. However, algae also need energy and carbon for their cell division and to extract nutrients such as phosphate and nitrogen from the water. Mooij took this fact as his starting point.

“The principle works as follows: we go to the nearest pond and fill a test tube with algae. Back in the lab, we put the tube in a reactor. Then we provide the algae with light and CO2 during the day. This is enough for them to produce oil, however they are unable to divide. They need nutrients for cell division and we only give them these in the dark. To absorb the nutrients, they use energy and carbon. This means that only the fattest algae can divide, as they have stored energy and carbon during the day. By removing some of the algae every day, the culture will eventually exist of only the fattest algae.”

Unfortunately, there is one important caveat, explains Mooij. “The survival of the fattest principle turns out to work beautifully. At the beginning there is a whole zoo of algae and, over time, the system does indeed almost become a monoculture. However, the fat alga is not producing oil yet. Algae do not produce only oil for energy and carbon storage, but starch too. Out test environment is selective where it concerns storage in general, but not yet for the specific storage of oil or starch. We will need to make the culture environment even more specific to achieve this. That’s what we are working hard at now.”

Peter R. Mooij et., al. Survival of the fattest. Energy & Environmental Science, 21 October. DOI: 10.1039/c3ee42912a.

Comments are closed.