For over three centuries, mechanical watches didn’t differ much from the pendulum clock invented by Christiaan Huygens in 1675. But the so-called ‘balance and hairspring’ principle now seems outdated thanks to Delft researchers who claim to have developed the most accurate mechanical watch ever.

“Am I already wearing the watch? Ha ha, no I don’t think I ever will,” says Dr Nima Tolou. “I don’t earn enough! The watch costs about 26,000 euros.” Tolou, who works at the department of Precision and Microsystem Engineering (3mE Faculty), is one of the Delft researchers who is revolutionising watch mechanics.

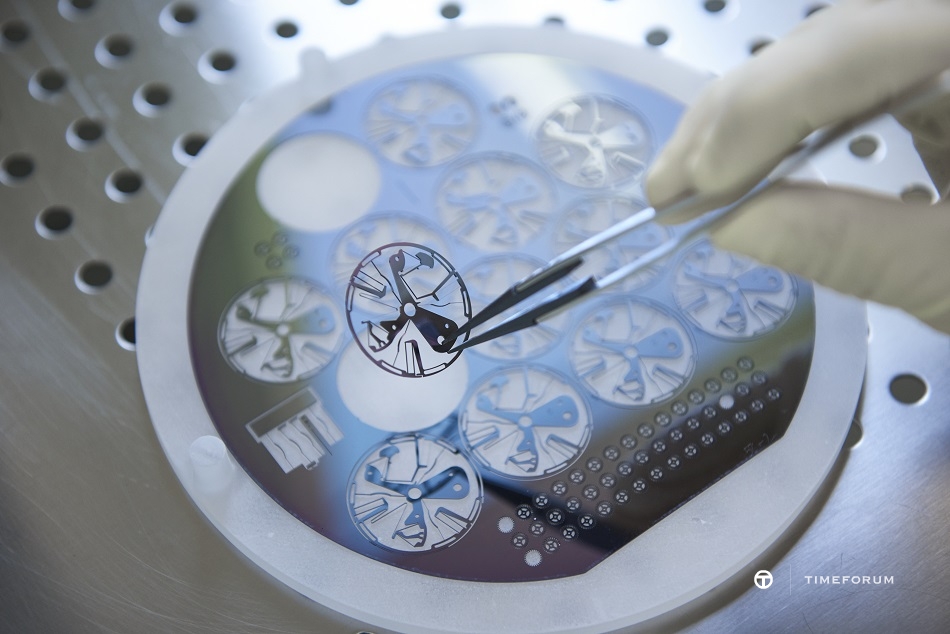

Together with the Swiss company Zenith and the TU Delft spin-off company Flexous, Tolou replaced the balance and hairspring mechanism with an oscillator fabricated from one single piece of silicon, thereby reducing the number of mechanical parts by thirty. The device is less sensitive to internal friction, magnetic fields and temperature changes, and is accurate to one second in twenty-four hours. This makes it the most precise mechanical watch ever, the developers say in a press release.

Sold out

“True,” says Tolou, “a fairly cheap electronic watch is even more precise. But it not as iconic as a handcrafted mechanical watch. I think mechanical watches will always attract people.” Tolou may be right. Earlier this month, the new watch, called Zenith Defy Lab, made its debut in a limited edition of ten unique pieces. They were all pre-sold. See th article ‘ Zenith Defy Lab Watch With 15Hz Movement Is ‘World’s Most Accurate’

The oscillator that forms the heart of the new watch may also be useful for a completely different application: the development of energy harvesters. Two years ago, Tolou received a Veni grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research worth 250,000 euros, to work on batteries that can recharge by harvesting the kinetic energy from vibrations in the environment.

“The principle is quite simple,” says Tolou. “With the watch we have shown that we can actuate the oscillator by applying an external energy source. Now we will turn this process around. The vibrations from the environment will put the actuator in motion. The movement of the actuator can be converted into electricity.”

‘Low power electronic devices will be booming’

The idea is that this technique can one day enable micro-electro applications to perform without batteries. By 2020, there will be over 20 billion wireless low-power electrical appliances, Tolou believes. “Low power electronic devices will be booming. Think about sensors that measure your sports performance and your heart beat, and all sorts of safety sensors in industry.”

The technique is challenging, however, because the environment’s kinetic energy frequency is usually very low and varied. Tolou thinks that his device can harvest energy from a much broader spectrum of frequencies than the energy harvesters that are around at the moment.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

tomas.vandijk@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.