Exactly one year ago, the latest research facilities at the Reactor Institute were inaugurated in a festive ceremony. What has the €35 million addition of a cold source delivered up to now? Delta takes a tour of the reactor.

Reactor is powered on. (Photo: Thijs van Reeuwijk)

We walk through a large heavy yellow door. First we enter a security space – a so-called ‘lock’ – before we can enter further. Information is requested about the photographer’s camera. Sneaking into the TU Delft Reactor Institute is impossible. Jeroen Plomp, the Head of the Instrument Group, explains that “We have a functioning nuclear reactor behind this door. You do not want a malicious person to just walk in.”

It feels special to stand inside the large distinctive dome. Several big instruments are arranged round a large basin. Overshoes on, we climb up a small staircase so that we can look into the pool. It is our first look at the blue light of the active nuclear reactor. It is magical. But you have the feeling that you must not fall in. Wim Koppers, the Director who is part of the tour, does say though that this would not be a problem. “You should definitely not get close to the centre though. Hypothetically you can swim here, but it is of course not the intention.”

Fishing for radioactive material

So we skip a dive in the eight metre deep pool. At first sight the equipment does look complicated, although not very modern. For example there is a row of fishing rods next to the basin. Plomp explains that they are used to put materials into a container. With good aim, these then hang in a pipe close to the reactor so that they become radioactive. “Once is it sufficiently radioactive, the operator collects the container.”

This sounds quite old fashioned while just a year ago the first use of the latest research facilities was celebrated. Total costs of the renovations: EUR 130 million (including the addition of the cold source at EUR 35 million). Did that amount not cover automating the fishing lines? “Admittedly it looks comical, but you want to make everything as safe as possible in the nuclear field. And this is a tested method that has little risks, and we have a permit for it,” explains Pomp. “The only disadvantage of this old method is that the amount of radiation we can generate is limited by the safety rules for the operator. That person has to remove the material from the container.” Plomp hopes that there will be an automated system that will use robotic arms that will further process the material behind radiation screens in the future.

Enough about swimming and fishing. Koppers, the Director, points to a small vertical pipe in the blue light, below to the left of the side of the reactor. This is the reason that we are here: the cold source. Koppers says that “It is the crème de la crème. The neutrons are slowed down there which enables us to carry out measurements more efficiently.” Plomp adds that “Some instruments have become 50 to 100 times better. Measurements that used to take us days can now be done in a couple of hours.”

Enormous cooling unit

How does the cold source work? To learn this we need to move to the next space. Overshoes off, wash hands, check the equipment for radiation, and back through the ‘lock’. There is a big, modern silver coloured extension outside. This enormous building is needed as a cooling unit to produce liquid hydrogen using icy cold gaseous helium. “The neutrons are first slowed down by collisions with plain water and, if they are lucky, they then collide with the liquid hydrogen which cools them further down and makes them move more slowly,” explains Jeroen Plomp.

There are pipes, handles, knobs and valves to open or close various parts sticking out of the building. It is tempting to push them. Plomp points to one of them, “This is the tap to fill the nitrogen vats inside. Everything is arranged in such a way that you cannot disrupt the very critical things.” He says that this accounts for some of the time and money it took to upgrade the units. “It’s about safety, it’s not just about building something new. Each part has been tested thoroughly. We made mock-ups of the entire unit before it was built.”

We follow the route of the cold neutrons. They fly out of the reactor, through the cold source where they are cooled and enter the next hall through a pipe. There, the bundle is split into four separate tubes. There are ‘neutron mirrors’ on the sides of the tubes between which the neutrons can move. “It can be compared to optical fibre,” says Plomp. “This allows us to make small turns and deflect the neutrons. The particles that you do not want, like the high energy gamma particles, go straight, leaving a clean bundle behind.” Plomp can draw out the clean bundles and divide the neutrons across various experiments.

Seeing roots grow

Many of the experiments are about studying materials. The neutrons are radiated through something and how they emerge from the other side or how they reflect gives information about what is in between. “We look with neutron eyes,” Jeroen Plomp describes it poetically. They research an incredible range of things. “From atoms and molecules whose exact shape we want to understand to big objects like a historical object whose exact composition we want to know,” adds Koppers, while he shows us an image of a small Van Leeuwenhoek microscope.

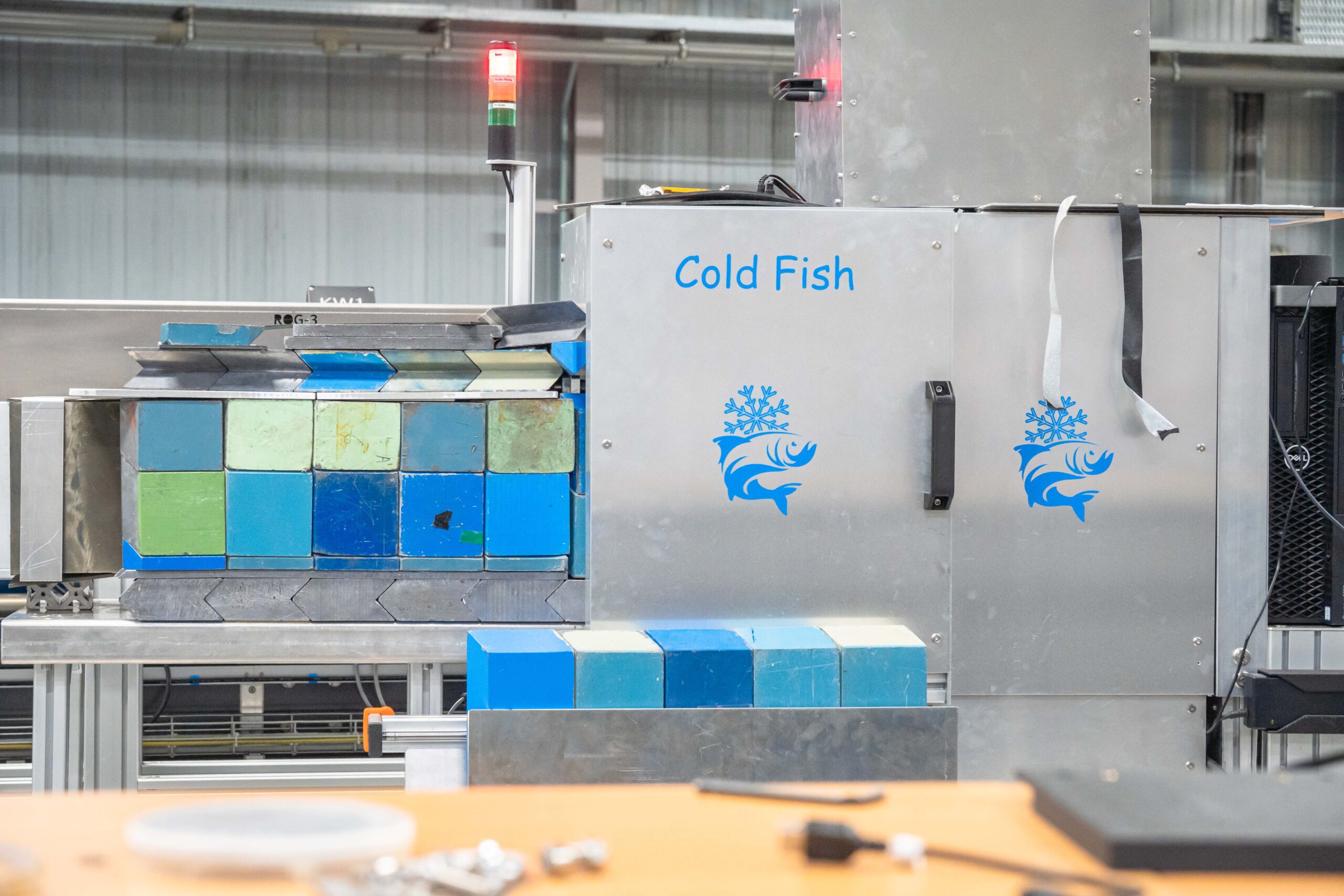

We stop at a big metal box, a piece of equipment called ‘Cold Fish’. A German researcher is working on testing home-made instruments. He cannot do this type of research using cold neutrons in Germany at the moment.

Apart from a couple of large plastic growing containers, there is little to see. But the next experiment using the Cold Fish is ready. It involves researching the effects of climate change. “We will work with the University of Canada to examine the water uptake of plant roots,” says Plomp. “We want to see how the roots react under various conditions, for example during dry or very wet periods. Our imaging bundle will let us track how the roots develop in a non-destructive manner.”

Cheese spread and chicken pieces

It sounds strange, plant research in a reactor institute. But it can be even crazier. We stand next to a huge yellow pipe. Wim Bouwman (Associate Professor of Radiation Science and Technology) is working on cheese spread and chicken pieces. “I have worked with the reactor for 25 years already and have designed new neutron diffraction techniques. This allows me to look closely at the structure of foodstuffs. I started with milk and yoghurt, moved to cheese spread, creams and emulsions like mayonnaise, and now I’m looking more and more at meat alternatives.”

Bouwman explains how meat alternatives are made. “Vegetarian chicken pieces, for example, are made by pressing proteins through a kind of mincer at high pressure and temperatures. But what exactly happens in this process is a sort of black box.” Until now that is. Bouwman uses neutrons to study the process in detail. “We are trying to find out what happens at a very small scale, really at molecule level. If you know that, you can tweak the production settings in a more targeted way.” The goal is the perfect vegetarian chicken piece.

Are there any results? “It is a complex instrument. So we are now exploring how to obtain the very best measurements.” But Bouwman is positive. “I am very happy with the new equipment. The degree of measurements has been vastly extended thanks to the cold neutrons. We can now do a lot more research and more sensitive measurements.”

Researching thin layers

On to the next machine, a large pink piece of equipment – the neutron reflectometer. We may not take too many photos as a company is working on something confidential next to it. This is Lars Bannenberg’s domain. He is using the set-up to look at very thin layers. “Layers in solar cells, hydrogen sensors, batteries, coatings on a ship or tooth implants. We look on a scale of one ten-thousandth of the thickness of a hair, about four atoms piled on top of each other.”

What makes thin layers so interesting? “There are countless applications, such as in the chip industry,” says Bannenberg. “Or in chargeable batteries that work less well after a while. If you have a brand new telephone, you do not need to charge it much. But after a year, that changes as the battery is made up of different materials. There are all sorts of chemical processes in the interfaces. You can add coatings to keep them as stable as possible. And we can research these coatings here so that ultimately better batteries can be made.”

The machine is currently measuring a hydrogen sensor. This is also the topic of the first – and so far only – paper that has appeared with the cold source as an upgrade. How do they like the new equipment? “When we turned it on the first time, our reaction was that it is far faster,” says Bannenberg enthusiastically. “The reactor was not permitted to run on full power immediately, this is done according to a detailed protocol. When we were finally able to measure things, everything worked well. We got even more neutrons than we expected, though it did generate more noise. We have now sorted that out by adding extra shields to protect both ourselves and the system.”

Playground

On with the tour. We get to Plomp’s favourite spot where different instruments are set up. “This is my playground,” says Plomp. “I can build all kinds of new things, which I do a lot with the students. After the renovations, we became more of a user facility for scientists and companies, but we do a lot in terms of education. Generations of nuclear knowledge are disappearing as people retire. And we need that knowledge for things like materials research, medical applications, and research into nuclear energy. We need to teach new students. The Netherlands needs to become more nuclear.” Koppers adds “And these facilities will let us move forward over the next 30 years.”

What have the new facilities – the renovation of which cost EUR 130 million – brought after one year of use?

- One article published in American Chemical Society, with more articles being prepared

- 79 measured projects which Plomp says the expectation is that the measuring capacity can be doubled at least, given that some instruments are not yet running on full staff.

– 9 company projects (5 in NL, 4 international)

– 31 TU Delft projects

– 11 Dutch university projects

– 28 international university projects

- 12 bachelor/master projects

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

E.Heinsman@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.