A year after Putin plunged Ukraine into all-out war, academic freedom in Russia is in a sorry state. “You can stay and try to help others, or you can flee.”

How has the war changed the lives of Russian scientists? (Photo: Jan Reinicke / Unsplash)

Russian researchers who do not support Putin and speak out against the war on Ukraine can be prosecuted in their homeland. A considerable number of them flee the country. But the vast majority stay. How has the war changed their lives and their view of science? Two researchers – one who stayed and one who fled – tell their story.

Against the war

The large-scale attack on Ukraine by Russian forces started on 24 February last year. In that same week, the EU and various countries, including the Netherlands, put their formal collaboration with Russian universities on hold. Within Russia, it was clear that neutrality was not an option. Out of “love for the fatherland”, the rectors of the universities gave their full backing to President Putin’s decision to invade Russia’s neighbour.

But at around the same time, Universitetskaya Solidarnost, the only independent union for university staff, published an open letter in which academics spoke out publicly against the war. The signatories argued that a true patriot does not unquestioningly carry out what the state demands, but endeavours “to assert in his own country the principles of fairness, humanism and peace.”

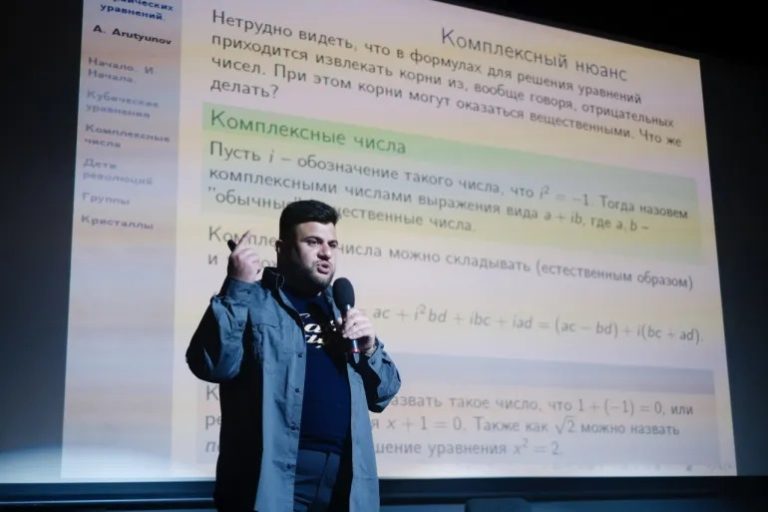

Despite the fact that anyone who voices opposition to the war risks a long prison sentence, the small union has not changed course, says Andronick Arutyunov (34), mathematician and co-chair of the Moscow Institute for Physics and Technology. “But we do exercise caution.” The names under the online letter have since been removed and the union’s leaders think twice before they make public statements. For instance, they still refrain from using the word ‘war’ and speak instead of ‘the so-called special military operation’. “That prevents problems.”

(Photo: Andronik Arutyunov)

Helping fellow academics

Even so, the union still faces plenty of problems. Over the past year, its membership has shrunk from thousands to a mere two hundred. One after the other, its remaining members are being arrested and charged. Arutyunov tries to provide them with legal assistance in such cases. “We enter into litigation. With varying degrees of success. Recently, an academic in Yekaterinburg suffered discrimination for the sole reason that he was a member of our union. We won that case. But it just goes to show: in the current polarised situation, members are taking a risk by sticking with the union and it adversely affects their job prospects too.”

‘After I was arrested, I came to the conclusion that it was better to leave’

Arutyunov also helps fellow academics to flee the country. They no longer feel free to do their job or are afraid of being called up for military service. “We give them contacts in other countries and arrange for them to get across the border. That’s steadily becoming more difficult because countries have closed their borders, though it’s still possible to enter Europe via Istanbul.”

One of these academic refugees is Pyotr Safronov (41). Since July, the philosopher has been a visiting researcher and lecturer at the University of Amsterdam and a fellow of the NIAS institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. “Until 2018, I worked at the department of education sciences at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, but I stopped because I no longer wanted to work for a state university.” He began working at a number of private schools and spoke out against the war. “But after I was arrested at a demonstration, I came to the conclusion that it was better to leave.”

(Photo: Pjotr Safronov)

(Photo: Pjotr Safronov)

If academic staff speak out against the war, repression is not the only problem they face. They are increasingly having to cope with restrictions. The first signs were already apparent a few years ago, says Safronov. “When I wrote a paper criticising the university’s dependence on state subsidies, it was ridiculed. The suggestion that educational policy should be supported by data was taboo as well. And the idea that students themselves could play a role in designing their studies was a step too far for department heads. And this was at one of the best universities in Moscow, on a par with Western universities. In the provinces it’s even tougher.”

Now academic freedom is rapidly being eroded. For instance, historians can be prosecuted if their research is not in line with the view of Russian history propagated by the Kremlin.

Arutyunov: “Humanities scholars and social scientists are less and less able to decide what they want to research”, says Arutyunov. And a lot has changed at the technical faculties too. “Institutes want their scientists to research new war technology and weapons. Unless you work for the military, you have little chance of a grant. Mathematicians like me are lucky: nobody ever knows what we are doing!”

Isolation

Since the war began, the Russian scientific community has become steadily more isolated. “International research projects have been stopped by foreign universities and by the Russian universities themselves”, Arutyunov confirms. But the researchers have a hand in these developments as well. “I still go to conferences in Europe, but many of my colleagues do so very rarely. They think their Western counterparts don’t want anything to do with them, so they don’t contact them anymore. That’s a real shame because there are still plenty of opportunities.”

‘If I flee, I don’t know whether anyone can take over my union work’

Safronov feels privileged that he was able to get out of Russia and that he has been able to build a new life for himself thanks to an international network and aid organisations. “Russian scientists find it difficult to make the move because they don’t know anyone. In many cases, they simply have no choice.”

Staying

But not all of them want to leave. “In Russia you live without hope”, Arutyunov sighs. “But I still want to stay. Although our situation cannot be compared with that of the Ukrainians, they at least have the hope that the war will end. Russians who are opposed to their regime have had no prospects for over 20 years. The academic world as we used to know it in Russia is dead. You can stay and try to help others, or you can flee. But if I flee, I don’t know whether anyone will be able to take over my work at the union.”

HOP, Peer van Tetterode

Translation: Taalcentrum-VU

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

redactie@hogeronderwijspersbureau.nl

Comments are closed.