The Netherlands started relaxing the corona measures on 1 July. Great news, but risky too. By screening all sewage installations the government keeps an eye on the virus.

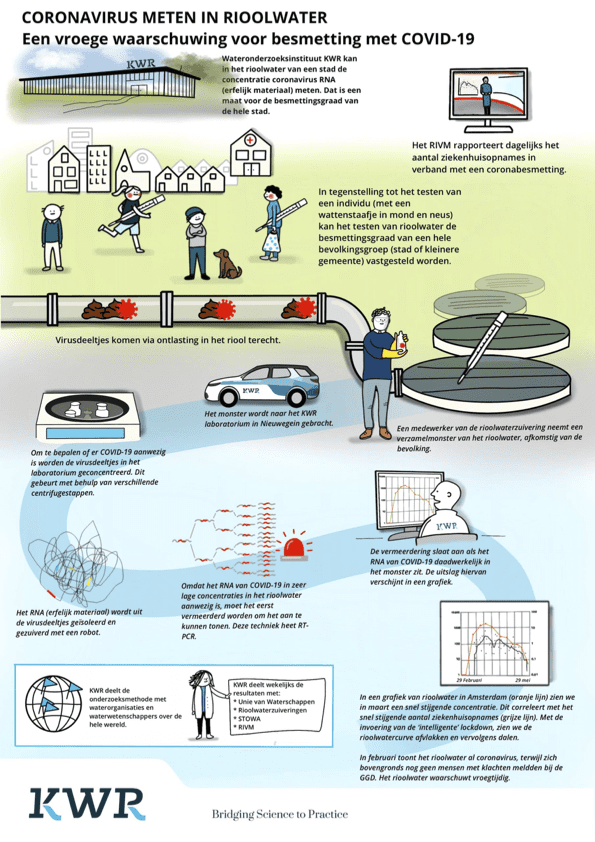

Sewage systems are a good reflection of society. (Photo: KWR)

Sports, the sauna and paid sex – these can all be enjoyed again. One reason why almost all activities are open again is that the Government is keeping tabs on your and my health by checking our poo. Your poo, my poo and everyone else’s in the Netherlands. Last week, Minister of Health Hugo de Jonge asked (in Dutch) the RIVM (Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment) to monitor the presence of the coronavirus in all 352 sewage treatment plants in the Netherlands.

Spokesperson Coen Berends (RIVM) says that 10 million people will covered by 79 test locations by mid July. But to cover the whole country, a disproportionately large number of up to 352 test points need to be added. The RIVM is now working on extending the national sewage water surveillance.

Diahorrea

“Sewage systems are a good reflection of society,” says part-time Professor of Water and Health at TU Delft, Prof. Gertjan Medema. Through the KWR water research institute in Nieuwegein, he is leading the research into traces of the coronavirus.

Over the telephone, KWR researcher Dr Frederic Beén said that “Analysing sewage water is very relevant for research into the health and behaviour of society. Ten years ago we already examined traces of drugs in waste water, and the RIVM has tested the incidence of diseases such as polio and hepatitis for even longer.”

From previous publications (December 2019) Medema had understood that many corona patients also got diarrhoea and that viral RNA and the virus itself were found in excrement. Medema thus decided to screen the sewage water for viral RNA for two reasons. One, he wanted to know if the virus spread through waste water; and two, to see if the screening of sewage sludge could be used as a means to monitor infections in a given area.

The first screenings started in February in the sewage treatment plants of Amsterdam, The Hague, Utrecht, Utrecht Overvecht, Apeldoorn, Amersfoort, Schiphol and, later on, in Tilburg. This was three weeks before the first coronavirus cases were confirmed.

Half a litre from a composite sample is enough for a laboratory analysis. (Photo: KWR)

The way things work, explains Beén, is that most sewage treatment plants have a unit that takes ‘composite samples’ over a 24 hour period. The unit takes a small amount of the impurified inflow every 5-10 minutes. The amount tapped is proportionate to the discharge (volume per second) at that point in time. This is thus a representative sample over one 24 hour period. KWR staff then took a little less than half a litre of the sludge and brought it – on melting ice – to the lab for further processing and analysis. To show the path taken from sewer to graphics, the KWR made a clear and practical poster.

Early and sensitive

“Initially, we didn’t find anything,” remembers Beén, “but on 5 March we spotted the first traces of Covid-19 in the sewage sludge of Amersfoort. That was a few days before the first group of people reported health complaints.”

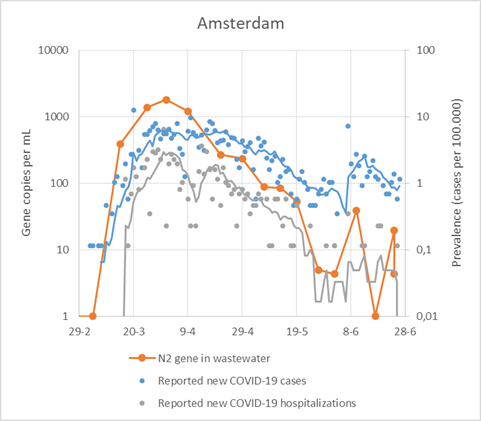

Later comparisons with the figures of the GGD (Community Health Services) led to the estimate that the virus was observable in sewage sludge from as few as 1-10 infections among 100,000 inhabitants. Viral RNA in the sewage water is thus not only an early indicator, but is also a very sensitive indicator of the presence of Covid-19 in an area.

This was big news. On 30 March, Medema and his colleagues published their article, Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 in sewage. A few days later, Nature followed with How sewage could reveal true scale of coronavirus outbreak and after that, followed just about every website and dailies including The Times (12 April) and the New York Times (1 May).

Scaling up

Encouraged by this success, and driven by the continuing increase in the number of cases in the Netherlands, the KWR extended the number of sewage treatment plants where they took samples to nine. Apart from this, the RIVM started screening at Schiphol mid February. In the same period, the virus was found in the sewage system of Tilburg and Kaatsheuvel, nearby the first Covid-patient admitted to the hospital and his family in quarantine. On the basis of this result, the RIVM has monitored 29 locations on commission of the Government from 1 April. That number will be extended to 79 by mid July, and later to the complete coverage of 352 plants on 1 September.

The concentration of gene particles in the sewage (red), the number of reported infections at the GGD (blue), and the number of hospital admittances (grey) in Amsterdam. Date: 24 June 2020. (Plot: KWR)

Prof. Ana Maria de Roda Husman (Head of the Department of the Environment at the RIVM’s Centre for Infectious Diseases) is responsible for the scaling up. To do this, she relies on the cooperation of the water boards. She is currently working on weekly screening while the Minister wants the sewers to be tested every day. In a telephone interview, De Roda Husman explained that “this is not always necessary. If the spread (of the virus, ed.) is slow, you do not need to sample that often. As the spread speeds up, so you need to take samples more often.”

Dashboard

Is the Netherlands unique in using this method of tracing? Yes and no. Testing waste water for the coronavirus is now being done across the world. “What is unique in the Dutch situation is that the screening will cover the whole country and all its inhabitants. It is also the only place where all the details will be collated centrally at one government agency, in this case the RIVM, where they will be combined with other surveillance systems such as hospitals and GGDs,” explains De Roda Husman. This makes the sewage treatment plant research programme an important part of the corona dashboard through which the Government is keeping tabs on the situation in society while easing the lockdown.

“We will see if the concentration (of the viral RNA, eds.) stays low or if it will start circulating again,” says Medema. He is no longer concerned whether sewage water is a source of contagion. “The sewage system is not a transmission route for Covid-19,” he concludes. The sewage system may contain viral RNA, but not the intact virus.

“The more infections, the higher the concentration of viral RNA,” says Medema. Does any one region stand out in the tested concentration of the number of infections? “The model is not yet quantitative,” says De Roda Husman. “We need to do further calculations and modelling for this.” At the KWR, in answer to this issue, Beén says that “this is being explored. To determine this you need to set up a mathematical model of the sewage system and of the quantity of waste matter. We are working on this, but it is still a work in progress.”

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.