TU Delft’s first satellite lasted an unexpectedly long time in space. But after 15 years, increased solar activity proved fatal to Delfi-C3 on Monday 13 November.

View on earth from the edge of space. (Photo: Pxhere.com)

“The last signals with our ground station I heard was on Monday 13 November at 07:23,” says engineer Chris Verhoeven, who led the building of the satellite 17 years ago. “Later that day, Delfi-C3 was observed over the Gulf of Mexico at 14:25 our time.”

In his laboratory, Chris Verhoeven keeps a double of Delfi-C3. (Photo: Jaden Accord)

“After that there were no more messages, so that must be where it came down. Not far from where the meteorite that ended the dinosaurs struck 66 million years ago.” Dr Verhoeven works at the Faculties of Aerospace Engineering and Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science.

During its last orbits around Earth, the satellite’s behaviour changed. The radio signals showed that Delfi-C3 tumbled much more than before. This could also be seen in the signals from the photodiodes on the side of the satellite, which registered more and shorter flashes of sunlight.

Less and less remained of the original altitude of 700 kilometres. As the satellite descended, the periods during which the signal could be received became shorter and shorter. They dropped from originally 10 to about five minutes before the satellite disappeared behind the horizon again.

The signal had also changed, writes Nils von Storch who manages the ground station. ‘The beeps you hear is the carrier signal of Delfi-C3 that goes on and off regularly. We had not observed a signal without data in previous years, that really only happened in the last few days.’

Recording of Delfi-C3’s last passage.

The announced end

Stefano Speretta manages the Delft satellites in space. He would like to see some more continuity. (Photo: Jaden Accord)

“It started in September last year,” says Dr Stefano Speretta, who is responsible for the TU Delft satellites at the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering. “The solar activity increased, warming and expanding the atmosphere. The air density at high altitude increased which caused the satellite to slow down and lose altitude.”

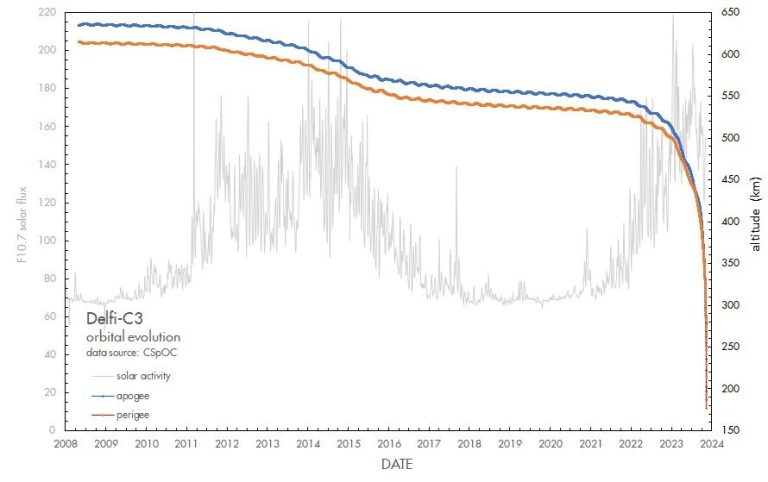

Satellite tracker Marco Langbroek published a graph on his website showing that peaks in solar activity coincided with Delfi-C3’s altitude loss.

‘The cubesat came down faster and faster (…) The orbit dropped by almost 100 km per day in the middle of its last day’, Langbroek wrote. Eventually the friction with the atmosphere became so intense that the satellite burned up in the atmosphere.

(Graph: Marco Langbroek)

Tough lady

Ten years ago, Verhoeven and his team celebrated Delfi-C3’s first anniversary. Amazed at the longevity of the homemade nanosatellite, he spoke of a ‘tough lady’. Experts estimate that had the sun not been so raging, Delfi-C3 would have lasted another two to three years.

“I was not that emotionally attached to it,” said Speretta, who became involved in the Delfi-C3 project eight years after its launch. “The scientific experiment was done after a few months, though.” The goal was to test a new type of solar panel in space. “The satellite lasted much longer than the six months expected. At one point the orbit was such that the satellite flew in sunlight for months. The satellite was never built to do this, but after three months in the sun it rebooted and emitted signals again. With the scientific goal long since completed, the new goal became to see how long it would last.”

No eternal life

Speretta favours a limited lifespan of about three years. A limited lifetime saves insurance costs for each satellite, it does not add that much to the swarm of satellites outside the atmosphere, and it fits better in the rhythm of education.

‘After Delfi-C3, things were too quiet for too long’

Building a new and better satellite every two or three years fits well with the length of a master’s programme. Moreover, the regularity in construction allows for incremental improvement. “You keep what works well and focus on new functionality. That’s how companies work, too. After Delfi-C3, things were too quiet for too long. Most of the people involved have left. This does not create continuity,” Speretta adds.

Speretta is certain that the Delfi-PQ mini satellite will also soon succumb to increased solar activity. Calculations show that the satellite will dive back into the atmosphere by the end of January 2024.

That only leaves Delfi-n3Xt (‘Delfi next’), which, after a miraculous resurrection in 2021, is now ‘non-operational’. In other words, there’s not much going on there. Delfi-n3Xt is expected to stay in space as a zombie for about 15 more years before it too breaks up and burns.

New generation

Speretta is looking forward to the launch of the anniversary satellite of the VSV Leonardo da Vinci study association and to the provisionally unnamed pair of Delfi-PQ satellites that will independently share the same orbit at a fixed distance from each other. He cites late 2025 as the launch date.

“Then we will have something to play with again. I mean, we want to continue building and flying satellites,” Speretta says. “Students tell me they came to TU Delft specifically to build a satellite. Surely that is the heritage of Delfi-C3.”

Delfi-C3 in figures:

- Launch: 28 April 2008

- Return: 13 November 2023

- Number of orbits around the earth: 85,059

- Speed: 7.5 kilometres per second

- Altitude: 600 – 700 kilometres

- Weight: 2.5 kilograms

- Power: 2.5 watts

- Experiments: solar panels, TNO solar sensor, radio transmitter and receiver

- Its own Wikipedia page

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.