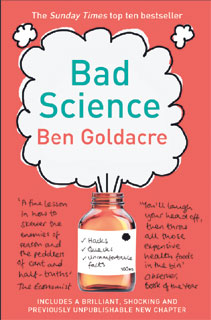

The media and advertising bombard us every day with so-called

scientific claims, most of which are just plain nonsense or ‘bad science’. Guardian columnist Ben Goldacre shines his light on some of the worst and most hilarious examples.

The world, especially in areas concerning health and nutrition, is teeming with scientific claims: there’s omega-3 in your butter to reduce the risk of having a heart attack, there’s the anti-oxidants in your fruit juice offering anti-aging benefits, there’s turmeric (or curry as the English call it) for reducing cancer risks, and so forth. While these are fairly well-known examples, some of the less well-known include Brain Gyms to improve blood circulation to the brain, fish-oil capsules to improve intelligence, and Aqua Detox to remove toxins from the body.

These supposedly sciency sounding claims are some of the hilarious examples of bad science cited in ‘Bad Science’, a popular science book written by science writer Ben Goldacre, who also pens a weekly science column called ‘Bad

Science’ in the UK’s Guardian newspaper and maintains the website

badscience.net.

Scientific claims, like the ones mentioned above, are easy to spot. They often begin with ‘Research has shown that…’ or ‘Eating X increases the risk of getting Y disease’. In his weekly columns, Goldacre evaluates the scientific evidence supporting these claims to see if it stacks up, and whether such conclusions are warranted. Those that don’t stack up earn the moniker bad science, or pseudoscience.

The book draws on Goldacre’s newspaper columns, but also goes further, enlightening the reader through illustrative and hilarious examples of bad science – the book is full of them, and they range from the dieting world and homeopathy to kinesiology and bad statistics – to expose these sciency claims, while also encouraging the reader to be critical and demanding of the evidence used to support such claims.

Amidst the debunking of the supposed health benefits of antioxidants, the quackery called homeopathy and the nonsense called Brain Gyms, the book also sends a serious message: ‘Bad science’ has a cost to society.

One such cost is illustrated with an example from the Netherlands. The book’s bad statistics section highlights the case of Lucia de Berk, a Dutch nurse convicted of murder using statistical evidence that later turned out to be dodgy math – a case of prosecutor’s fallacy.

Living in societies where most of our science information, or rather disinformation, is obtained through media channels, there is an implicit trust in the media that they have done their job of verifying the evidence. It is a sobering thought to think about the amount of bad science being peddled in the media. In such an environment, Goldacre’s book is timely and empowering. Yes, empowering!

‘Bad Science’ is a wonderfully well-written book that will change the way you regard and evaluate sciency sounding stories in the media. More importantly, in the long run, the book will also save you money, as you will avoid paying what Goldacre calls a ‘voluntary self-administered tax on scientific ignorance’. Now, who would want to be in that tax bracket?

Ben Goldacre – ‘Bad Science’, HarperCollins Publishers, April 2009, 288 pages, € 12.99.

“Met een tekort van acht miljoen euro op een begroting van 31 miljoen, kan men zelf de conclusie wel trekken: er moeten straks mensen weg”, aldus prof.dr.ir. Joost Walraven van de afdeling gebouwen en civieltechnische constructies. Ook prof.dr.ing. Ingo Hansen (transport & planning) constateert ‘grote onrust’, maar afdelingscollega prof.ir. Frank Sanders niet. “Het is niet het gesprek van de dag aan de koffietafel.” Toch kan ook hij zich voorstellen dat werknemers bezorgd zijn.

Het personeel is het niet altijd eens met de conclusies van de commissies. Zo kan het advies van de commissie Stuip om onderzoek misschien niet in het grote bouwlab te doen, op weinig sympathie rekenen. Walraven: “Dan kom je in een neerwaartse spiraal. Er komt dan geen hoogleraar met kwaliteit hier naartoe. Goed onderzoek is zonder groot lab onmogelijk.” De door de commissie Rots voorgestelde samenwerking van de onderzoeksafdeling gebouwen en civieltechnische constructies met de afdeling bouwtechnieken bij Bouwkunde, kan wel op voorzichtige goedkeuring rekenen. “We vullen elkaar netjes aan”, vertelt Walraven, “maar het risico is dat je moet afslanken. Je moet erg oppassen dat de kwaliteit van de opleiding niet vermindert.”

Verder kan de bevinding dat er bij transport & planning onvoldoende wordt samengewerkt (rapport commissie van Binsbergen), rekenen op instemming van Hansen. Sanders ziet dat echter anders. “Ik kan me niet vinden in het woord ‘onvoldoende’. Maar het zou wel beter kunnen.”

Meer aandacht voor communicatie en managementvakken, zoals de commissie Stuip aanbeveelt, ziet Sanders (tevens opleidingsdirecteur) niet zitten. “Studenten hebben in ons vernieuwde onderwijsprogramma – dat 1 september wordt ingevoerd – al voldoende mogelijkheden tot verbreding. Ik denk ook dat er uiteindelijk juist meer behoefte is aan inhoudelijke kennis, ook vanuit de beroepspraktijk.”

Hansen gaat nog een stapje verder: “Aandacht voor nog meer projectmatig onderwijs en softe vakken, lijkt mij niet juist. We zijn door het college van bestuur nu al gedwongen om de minor in te voeren. Wij moeten daardoor vakken uit de bachelor naar de master verplaatsen. Dat doet de kwaliteit van de opleiding geen goed.”

Tot slot vond Walraven de opmerking van decaan De Quelerij in Delta 07 opmerkelijk dat het ‘nog een geluk bij een ongeluk is dat ik veel 58-plussers in huis heb’. “Met die mensen gaat straks een hele berg ervaring weg en hun taken blijven gewoon liggen. Moeten studenten straks soms elkaars werk nakijken?”

Binnenkort horen de wetenschappers meer. Hansen: “We verwachten eind van deze week meer informatie van de decaan.”

Comments are closed.