Outgoing State Secretary Vijlbrief’s draft decision about a borehole in a deep clay layer and seismic risks to the research reactor requires additional information from Geothermie Delft. The geothermal consortium is trying to meet this demand.

Phil Vardon, chief scientis of the Delft Geothermie project, was closely involved with the drillings. (Photo: Thijs van Reeuwijk)

“There have been some setbacks while drilling the injection well,” says geothermal research leader Professor Phil Vardon (Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences). Delta wrote about this last month. “The first time the production well (where the hot water rises, Eds.) was drilled, it went smoothly. Complications only occurred during the second time, which, incidentally, are not uncommon in drilling.”

But the extra information requested by the Secretary of State for licensing is largely separate from the technical problems in drilling. The extra information needed is related to a revision of the Mining Act that took effect on 1 July 2023. The TU Delft wells were drilled during the same period (June to October 2023), but there was no causal link between the – what turned out to be disappointing – operations and the extra information required on seismic risks.

Geothermie Delft (GTD) project developer Marc Pijnenborg explains it as follows. “Geothermal energy in the Netherlands started with a few greenhouses, but there are now more than 20 geothermal projects. This led to the Mining Act being amended to better cover geothermal heat extraction.”

For the TU Delft geothermal project, which is a consortium of TU Delft, contractor Aardyn, Energie Beheer Nederland (EBN) and Shell, the additional information required revolves around two issues.

- The effects of a drilled clay layer between two layers of water some two kilometres deep. And:

- The potential effects of seismic changes caused by geothermal extraction on the research reactor.

Insufficiently sealed mother hole

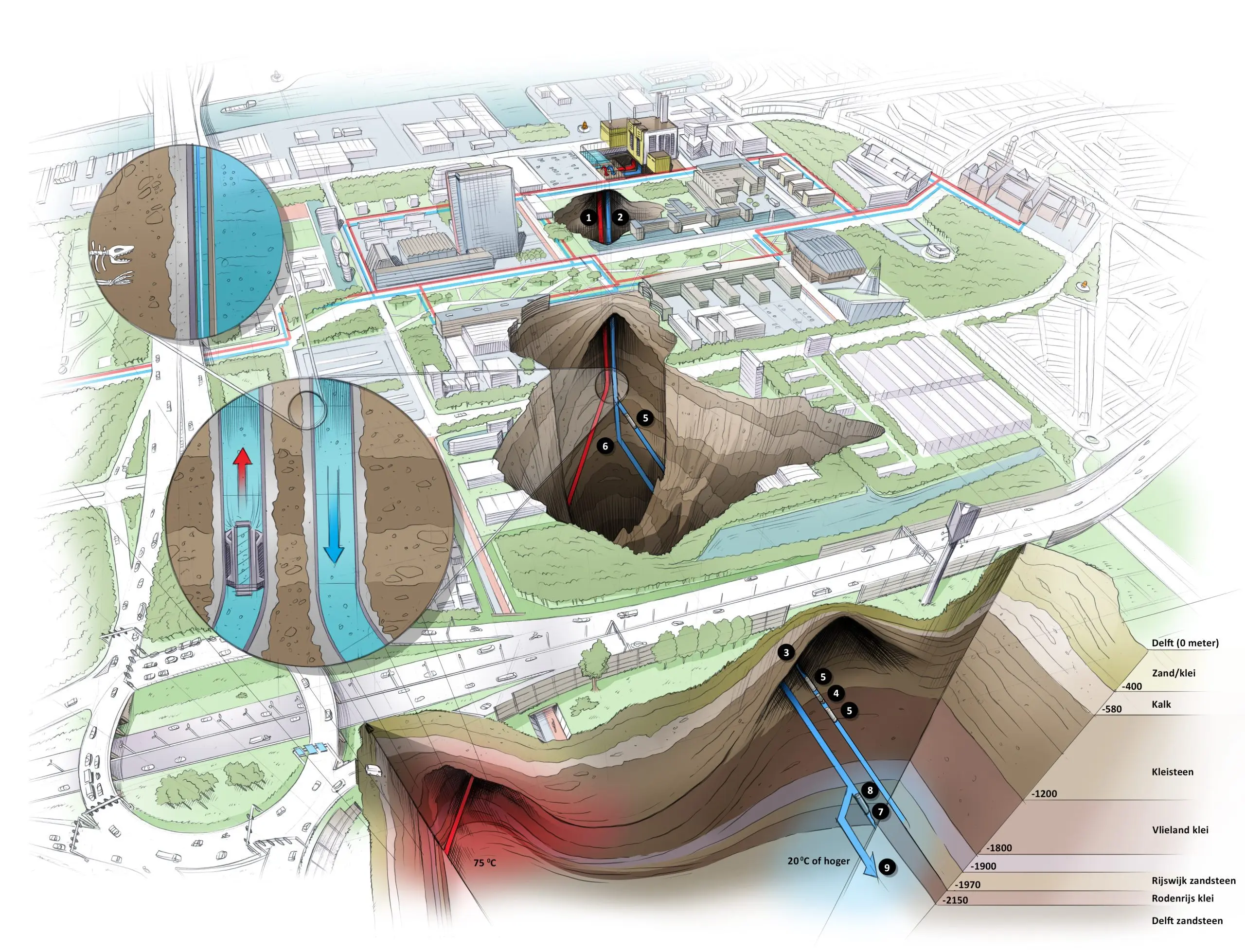

Towards the end of the drilling of the injection well, the contractor observed that halfway down, at a depth of about 1,200 metres, the wall of the 30-centimetre-wide borehole was beginning to collapse (position 3 in drawing). This could be seen through the coarse material emerging in the flushing water. There are several techniques to remedy a collapse, but shortly afterwards the drill head also got stuck immovably (4). However, the drilling team did manage to place three cement plugs (5) and plug the unused drill hole (the ‘mother hole’). However, the hole in the lower clay layer could not be closed. The contractor made a ‘side-track’, a process in which the drill bit is first sent straight down the hole and then goes parallel to the original drilling. This is a common technique when a borehole fails.

Towards the end, at over 2,000 metres depth, a second instability (7) occurred. This occurred slightly below the 70 metre thick clay layer between the water-bearing layers of Rijswijk sandstone and Delft sandstone – the production reservoir. As a result, the borehole became unusable at the last moment. Again, a 100 metre cement plug was installed and a second side-track (8) was drilled.

“What the State Supervision of Mines (SodM) does not like, and neither do we, is that the clay layer, which is the sealing rock of the hot water reservoir, was not sealed as it should have been,” Vardon explains.

In a letter to the State Secretary, SodM also writes that ‘Because the mother hole punctured all layers and was not properly sealed, the integrity of the sealing layer is not guaranteed, and this may put the reservoir in contact with permeable, shallower formations.’

Compress slowly

According to the contractor and Vardon, the hole in the clay layer will slowly compress. They demonstrated this to the regulator using models and calculations. But the regulator states that ‘SodM cannot follow the reasoning because there are no references, and the models are not substantiated. A flow to shallower layers is not permitted and the analysis cannot exclude whether this flow may occur.’ The regulator advised the State Secretary that ‘the executor must demonstrate that the integrity of the sealing layer is sufficiently secured’ before any heat extraction takes place.

‘Of course SodM continues to ask questions. That is their job’

“We calculated the worst-case scenario for SodM should the hole remain open,” Vardon says. “And of course SodM continues to ask questions. That is their job, and we will try to answer them by sharing all the knowledge and models we have. By the way, cement plugs protect shallower water layers down to about 1,150 metres.”

Vardon expects that in the worst-case scenario – an open connection between two aquifers – more pressure will be needed to access hot water. This would make the well less efficient in the sense that more electricity would be needed to pump up the same amount of underground heat.

Seismicity and research reactor

“The new Mining Act has added a major component,” says Marc Pijnenborg. He is GTD’s project developer and is employed by a geothermal energy developer called Aardyn. “And that is seismicity , and how to deal with it. Using conservative assumptions, we have to calculate the maximum earthquake that geothermal extraction could trigger here for the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate.”

Unlike Geothermie Delft, SodM believes the project is a medium-risk venture and this is the reason that the regulator is asking for data and models on the potential seismic effects of heat extraction. Of particular interest is the risk to the research reactor because it contains valuable infrastructure that could be vulnerable to earthquakes. What then would be the costs?

‘Shrinkage in the subsurface would create stress’

“Reinjecting cooled water of say 20 degrees, may cause shrinkage in the subsurface,” Vardon explains. “This would create stress, and the question is then how that would discharge. If all stress is released at once, it could cause an earthquake of magnitude three on the Richter scale.” That may sound hefty, but geophysicists say that these magnitude earthquakes are hardly felt. “Given the composition of the soil, it is much more likely that the stress discharges in a series of smaller slips,” Vardon stresses. “These have a magnitude of zero on the Richter scale.”

Pijnenborg is also aware that “A magnitude three earthquake sounds dramatic,” but he stresses that, according to TNO, a sudden discharge is very unlikely in a water-bearing sandstone layer. A geothermal project has only been shut down once in the Netherlands because of seismic risks, and that was near Venlo on a limestone subsoil with fault lines.

Despite the unlikelihood, a magnitude three earthquake is still the starting point for a study into the cost of a similar event on the research reactor. “We got in touch with the TU Delft Reactor Institute to find out what the consequences of a magnitude three earthquake could be on the building and research facilities,” says Pijnenborg. For objectivity, GTD wants to outsource that seismic survey to external experts. The TU Delft Reactor Institute refers to GTD as a spokesperson in the seismic survey.

What consequences could an investigation have? According to Vardon, the regulator may choose to keep the temperature of the return water higher. That would mean less stress build-up in the subsurface, but also less heat extraction for the project. A restriction on heat extraction, like a hole in the capping layer, would further reduce the efficiency of geothermal extraction.

Delay?

Will these additional studies also mean delays in completion, and the supply of heat to the campus and 5,000 Delft households? Vardon expects not. Building up the above-ground installations will take at least another year, so geothermal heat extraction would not start earlier than spring 2025 anyway. That, in his estimation, is enough time to supply all the requested data. Much of that data, by the way, is already being transmitted continuously even now.

Pijnenborg estimates that it will be the end of 2025 before all the preparations have been done, contracts signed and the heat network constructed. By then, he also expects the additional studies requested by SodM to have been completed.

In the meantime, Vardon wants to construct a shallow heat buffer at a depth of about 200 metres. It will involve a buffer of 500,000 cubic metres where hot water from deep underground will be stored in summer for use in winter. Exploratory drilling will start next spring and the shallow heat storage should make the heat network more efficient.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.