After a few days of rain, the water level in Limburg suddenly shot up. What was going on? Were we well prepared? And was it due to climate change?

The village Steyl near Venlo was prepared for the worst (Photo: Collection Emma Dijkstra)

Main photo by Jenske via Flickr

This summer, TU Delft student Emma Dijkstra received alarming messages on her WhatsApp. Her family (father, mother and brother) in Maastricht had been ordered to leave their home. They live there in the beautiful Heugem neighbourhood with a view of the River Meuse. But that was exactly the problem. It was Thursday, 15 July 2021, and the river was expected to rise by between 0.8 and 5 metres. Neighbouring houses were evacuated as a precaution. “You really need to get out of here,” a law enforcement officer told her father. They moved things from the basement onto tables and left later that night to sleep at a friends’ house. “I wish I could have done something,” says Emma afterwards. But she was too far away in Delft, where she studies Industrial Design Engineering. “I felt useless. And we didn’t know how high the water would come.”

Household goods brought up from the cellar out of precaution (Photo: Collection Emma Dijkstra)

“It was an extreme event,” Prof. Pier Siebesma says looking back. He is Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences and also works as a researcher at KNMI. “A low-pressure area lingered over the border area between Belgium and Germany for days. Areas of low pressure draw air from the surrounding area. The air was extremely humid because it was warm and it had rained a lot in the previous weeks. The air gathers in the low-pressure area and is squeezed out like a sponge. Normally a low-pressure area moves with the flow in higher layers of air – the jet stream. This time, it stayed in place and on Tuesday and Wednesday there was up to 150 mm of rain locally. The Netherlands normally receives 800 mm in a whole year. The weather forecasts had predicted this correctly, by the way.”

“I went straight there on Friday,” says Emma. The train went no further than Sittard, but her mother was able to pick her up by car. Once at home, she saw that the water in the Meuse was higher than she had ever seen before. At the flooded campsite on the other side of the road, she saw caravan roofs sticking out of the water. The living room was still full of things from the cellar. In the cellar, the water had not risen above ankle height.

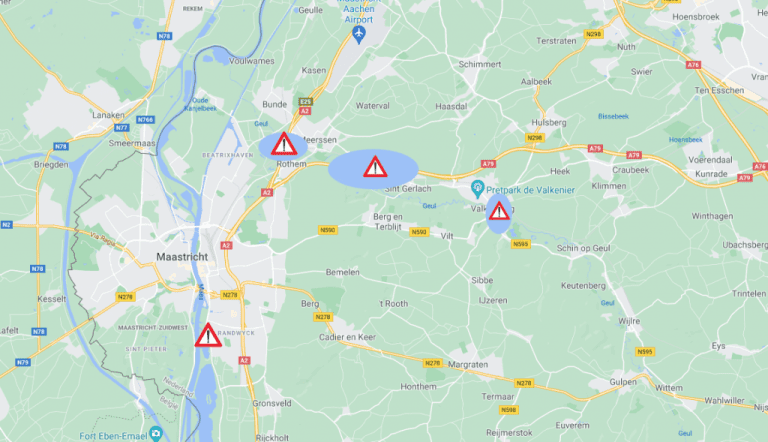

Flooded areas near Maastricht (Image: Google Maps, adaptation Jos Wassink)

Flooded areas near Maastricht (Image: Google Maps, adaptation Jos Wassink)

Smooth drainage

“The dikes along the Meuse held up well,” says Prof. Bas Jonkman. According to the Professor of Hydraulic Engineering (Faculty of CITG), the problem this time lay mainly with the tributaries. For example, the small Geul River burst its banks, causing a great deal of disruption in Valkenburg. The A2 and A79 motorways were also temporarily closed. “High water levels in the main river create problem at the entrance of the tributaries. The tributary cannot discharge its water into the main river and the water accumulates and rises, not only from the tributaries themselves but also from the rainfall in the entire catchment area. We need to take a closer look at that effect.”

A second point of attention for Jonkman is the role of water buffers. The De Dem water storage facility near Hoensbroek overflowed and the army had to be called in to reinforce its walls with sandbags. Residents of a lower lying residential area were worried. “They were fearful that the buffer was not solid enough, or insufficient account had been taken of the flood risk,” says Jonkman.

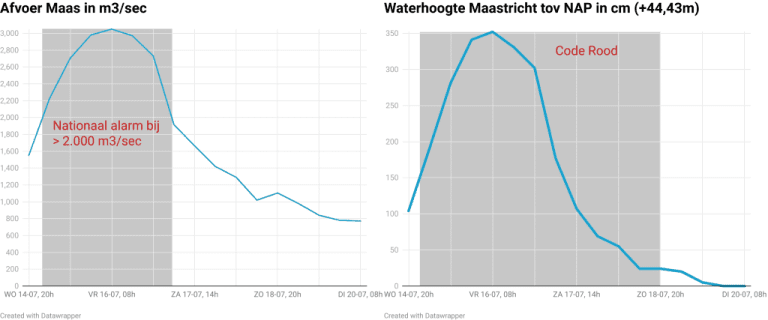

The high water levels didn’t last long. Left: the Meuse discharge, right: the water level. (Graphs: Jos Wassink with Datawrapper, data from Rijkswaterstaat)

After the floods of the Meuse in 1993 and 1995, many measures were taken to improve the discharge of the river water. Under the Room for the River programme, Rijkswaterstaat (the executive arm of the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment) created flood plains and dug secondary channels. Did that help? “Each project makes a difference of a few centimetres in the water level,” says Jonkman. “As a whole it worked well because even though the amount of water flowing through the Meuse was more than it was in the 1990s, the water level was lower.”

On Saturday, the water had already subsided considerably, including around the caravans. Swathes of brown mud covered the grass. The sun had broken through and the terraces in the city centre were open again. On her way there, Emma saw the water churning under the bridge: wild, brown and dirty. But it was a lot lower than before. “It’s very strange that the water goes away so quickly,” she says.

As he did with previous floods in New Orleans, Thailand and Houston, Jonkman has again set up a fact-finding mission, this time in collaboration with Deltares and KNMI. Data collected on rainfall, rivers, crisis response, damage and public health will form the basis for a report and a meeting, physical or otherwise, at the end of September. For the time being, Jonkman thinks that more attention will have to be paid to improving the discharge of small rivers, for example by constructing side channels, and to the safer construction of drainage basins.

Climate change precursor?

Many people see this flood as a consequence or even a precursor of climate change. How does Siebesma view this? “To some extent it is. In Europe, climate change has made it two degrees warmer on average, and for every degree warmer, the air contains 7% more water. So climate change brings more moisture into the atmosphere. But whether the standstill of a low-pressure area is a consequence of climate change, we do not know yet. A colleague of mine, Geert Jan van Oldenborgh at the KNMI, is going to research this.”

Mind you, there is something to be said for it. The jet stream, which carries high and low pressure areas, is driven by the temperature difference between the poles and the equator. As temperatures rise, especially in the Arctic, the drive of the jet stream, which meanders from west to east, weakens. Coincidentally, a study of quasi-stationary low pressure systems was published in early June in which the researchers write ‘Our simulations show that in Europe, systems with extreme rainfall move more slowly due to climate change, further increasing local exposure to extreme precipitation’. Intense rainfall could be 14 times stronger by the end of the century, they have calculated.

“The theory sounds plausible,” says Siebesma. “But we don’t know if the speed of the jet stream really did go down, or if its meanders have grown larger.” He would like to work with the KNMI to analyse weather data from the past 40 years to see if it reveals any of the predicted changes in the jet stream.

“We were very lucky,” says Emma afterwards. “I have friends whose house was completely flooded.” How do her parents look back on it? “They are going to prepare better. They are going to prepare sandbags just in case, and they are going to take valuables and important documents up to the attic. But moving? No, not really.”

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.