With his single photon detector, Dr Sander Dorenbos believes he can make communication more energy efficient and safer.

“Recently thousands of usernames and passwords for Hotmail, Google and Yahoo accounts have been illegally posted to the internet.

That should never have to happen again, thanks to the nano spiral photon detector.”

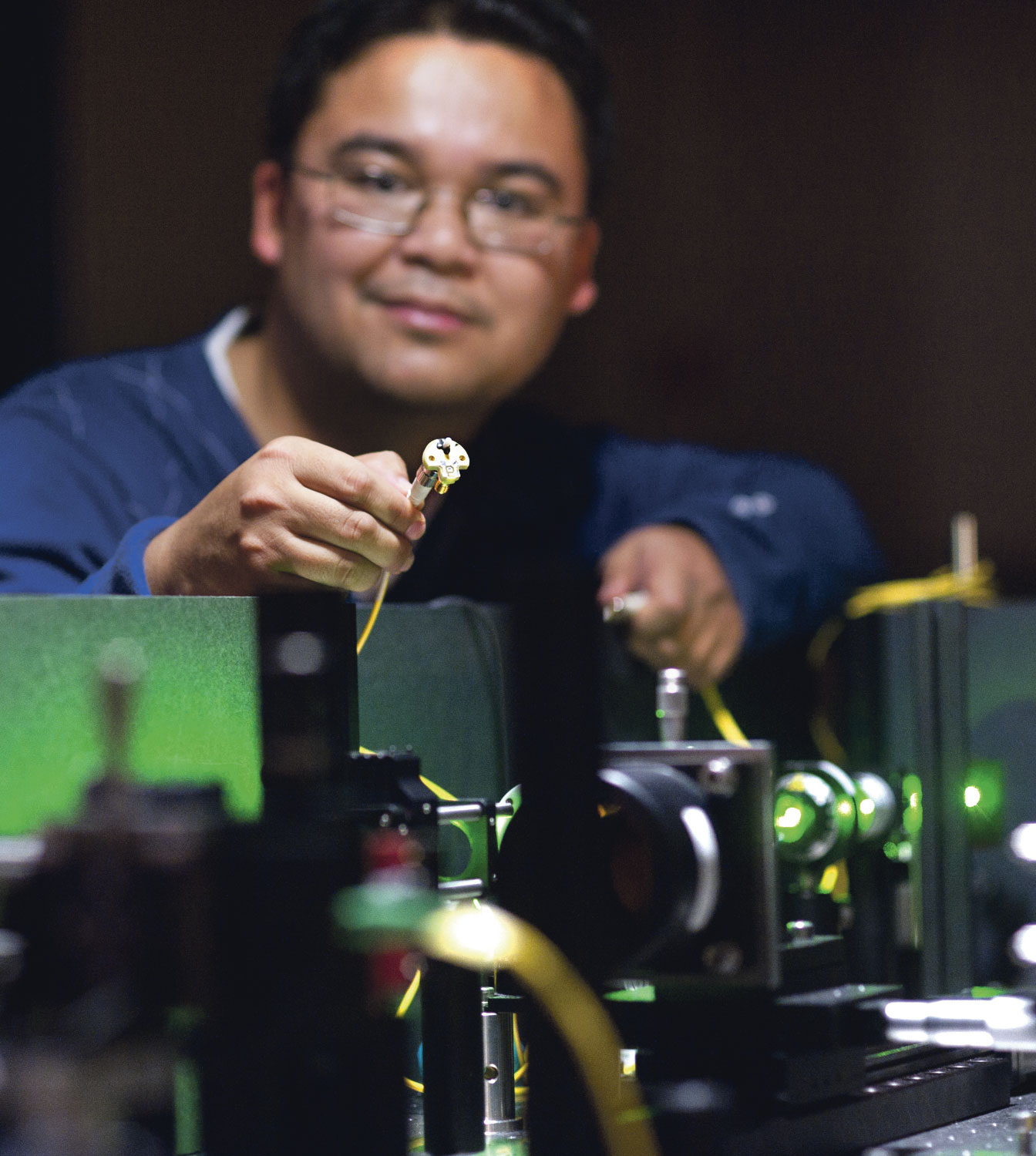

Sander Dorenbos knows how to promote his findings, or so the poster about his detector, posted next to his office door, illustrates. Last week at the faculty of Applied Sciences, the young researcher defended his PhD thesis about a sensor that can detect a single photon.

Nowadays we communicate with each other by sending huge amounts of photons through fibres. The internet would be much more energy efficient however if we were to use only one photon for each bit of information, according to Dorenbos. Besides, it’s also impossible for hackers to read out the information encrypted in a single photon without disturbing the flow of information.

In order for this quantumcryptography to work, very sensitive sensors are required. Single photon detectors already exist, but these detect photons in the visible light spectrum. What is new about the work of Dorenbos and his colleague Val Zwiller (who was one of Dorenbos’ PhD promoters) is that they ameliorated a sensor – first developed by Russian researchers – which detects single photons in the infrared and near infrared spectra, the spectra used for communication.

“These photons contain very little energy, making them even more difficult to detect,” Dorenbos explains. “The sensor consists of a spiral made of niobium titanium nitride, which is superconducting at 4 Kelvin and carries current. If it is hit by a photon, it is no longer superconducting and we register a little peak in the voltage.”

Since the photons have little energy, many of them pass by unnoticed. Dorenbos placed a small mirror behind the spiral to bounce them back, giving them a second chance to hit the spiral.

“When I visited the website of my nephew, the artist Rob Thijssen, I was struck by how well his painting suited my PhD research,” says Hugo Hellebrand (37), who is with the hydrology group and will defend his dissertation on the 23 November. “There’s a curve in the painting that reminded me of water flowing under the pier of a bridge. It also made me think about the horizons one makes of the soil. Lastly, I like that it’s called ‘Landscape’, because that plays an important role in my research.”

Hellebrand wrote his dissertation on the influence of precipitation. He focused on how rain water enters into rivers in hilly landscapes. “There are very complex models for these processes. They need a lot of parameters, but all the information isn’t always around. I therefore made simpler tools, which do not need a lot of parameters. With these tools one could use geological information, of land use, like how many trees there are in the neighbourhood, and soil property images, to predict the influence of precipitation.”

Comments are closed.