On cloudy nights, light pollution turns the night sky of Delft a bright orange. Let’s start designing for darkness, Dr Taylor Stone proposes in his research.

Light pollution regularly turns the night sky of Delft orange. (Photo: Nina van Wijk)

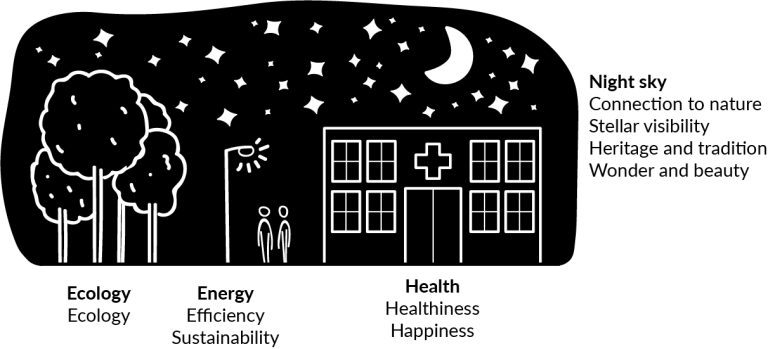

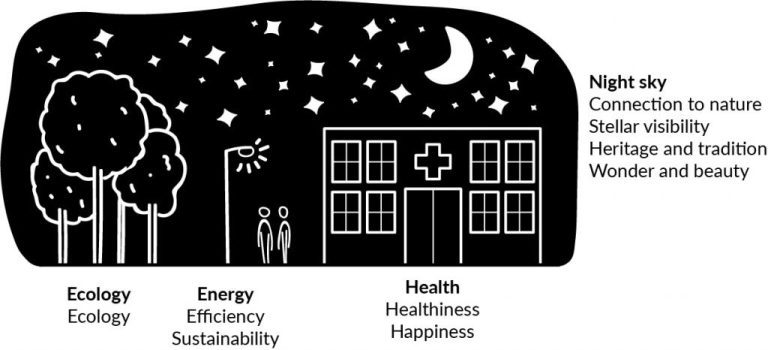

Stone proposes nine values of designing for darkness, which can be grouped under four main categories: ecology, energy, health and night sky. (Illustration: Nina van Wijk)

Stone proposes nine values of designing for darkness, which can be grouped under four main categories: ecology, energy, health and night sky. (Illustration: Nina van Wijk)“It wasn’t until halfway through my thesis that I started thinking more about darkness than about lighting,” Dr Taylor Stone admits, when asked what triggered him to focus on designing for darkness. Stone recently defended his PhD thesis at the Ethics and Philosophy of Technology section of the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management. In his thesis, Stone proposes to design for darkness by incorporating nine values of darkness. His starting point was quite the opposite, namely focusing on the negative effects of artificial lighting. Examples of these effects are energy wastage; harm to ecosystems and wildlife; detrimental effects on human health and well-being; and the hindered experience of the night sky.

Stone proposes nine values of designing for darkness, which can be grouped under four main categories: ecology, energy, health and night sky. (Illustration: Nina van Wijk)

Stone proposes nine values of designing for darkness, which can be grouped under four main categories: ecology, energy, health and night sky. (Illustration: Nina van Wijk)

Nine values of darkness

If you want to tackle the negative effects of lighting, Stone thought, why not focus on the positive effects of its opposite: darkness. By using his nine values (illustrated above), he aims to revalue what darkness is and can mean for us, for our health and for our environment. Sounds quite soothing, considering that the most easily accessible night sky is on Google rather than in our immediate surroundings. To make his philosophy more tangible, the doctor of darkness puts forward practical applications in which these values can be used.

The doctor of darkness puts forward practical applications

Adapting street lighting

One of these applications is street lighting. “Two things seem to be aligning right now: retrofits in LED street lighting around the world and rising environmental awareness about the negative effects of light pollution.” This alignment can be used to incorporate his perspective on darkness. Dark main roads with responsive lighting come to mind, but Stone stresses that the goal is not to eliminate artificial lighting altogether. “We want to create a better balance between lighting and darkness, and rethink the function of lighting.”

Dimming lights step by step

‘Incremental darkening’ is an example of rethinking this balance. People tend to get used to the way their surroundings look, including the level of brightness at night. Turning off all the lights in the city centre from one day to the next might not be such a great idea then. New LED lighting can be dimmed easily, which is one of the design solutions he proposes. “You can dim the street lighting slightly each year for example, so people can get used to it.” Over time, this would lead to less light pollution.

Dark parking

Street lighting is a starting point, but in his research Stone looks further. Together with two colleagues, he proposes autonomous vehicles as a possibility for designing for darkness. “Right now, autonomous vehicles are being designed and developed. This creates a window of opportunity to incorporate designing for darkness values into the design requirements.” Stone envisions a world where parking garages are kept dark. The passengers get out of the car, and it parks itself in the garage. “What is the purpose of lighting if there are no people?”

Implications for safety and education

Safety is one of the initial responses to his ideas, and he stresses that this is important. He views his values as a starting point but acknowledges that designing for darkness has social, institutional and legal implications which need further attention.

Proposing design values at a university that teaches designers and engineers creates an interesting intersection, but Stone has not thought yet about how to incorporate his design values in education. “That is certainly a good question. It would be good to promote these values in innovation.” As a pioneer in the field, it might take a while before the values trickle down to other areas. In the future, however, people might look back at the orange sky in horror, and starry nights will become ordinary once again.

- Taylor Stone, Designing for Darkness: Urban Nighttime Lighting and Environmental Values, PhD supervisors Prof. Jeroen van den Hoven and Dr Pieter Vermaas at the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management TU Delft, 21 January 2019.

Nina van Wijk / science editor trainee

Comments are closed.