Doctors have been repairing a congenital heart defect in children with GORE-TEX tubes for 20 years. Now that these patients are adults, the passage appears to be too tight, Delft flow calculations show.

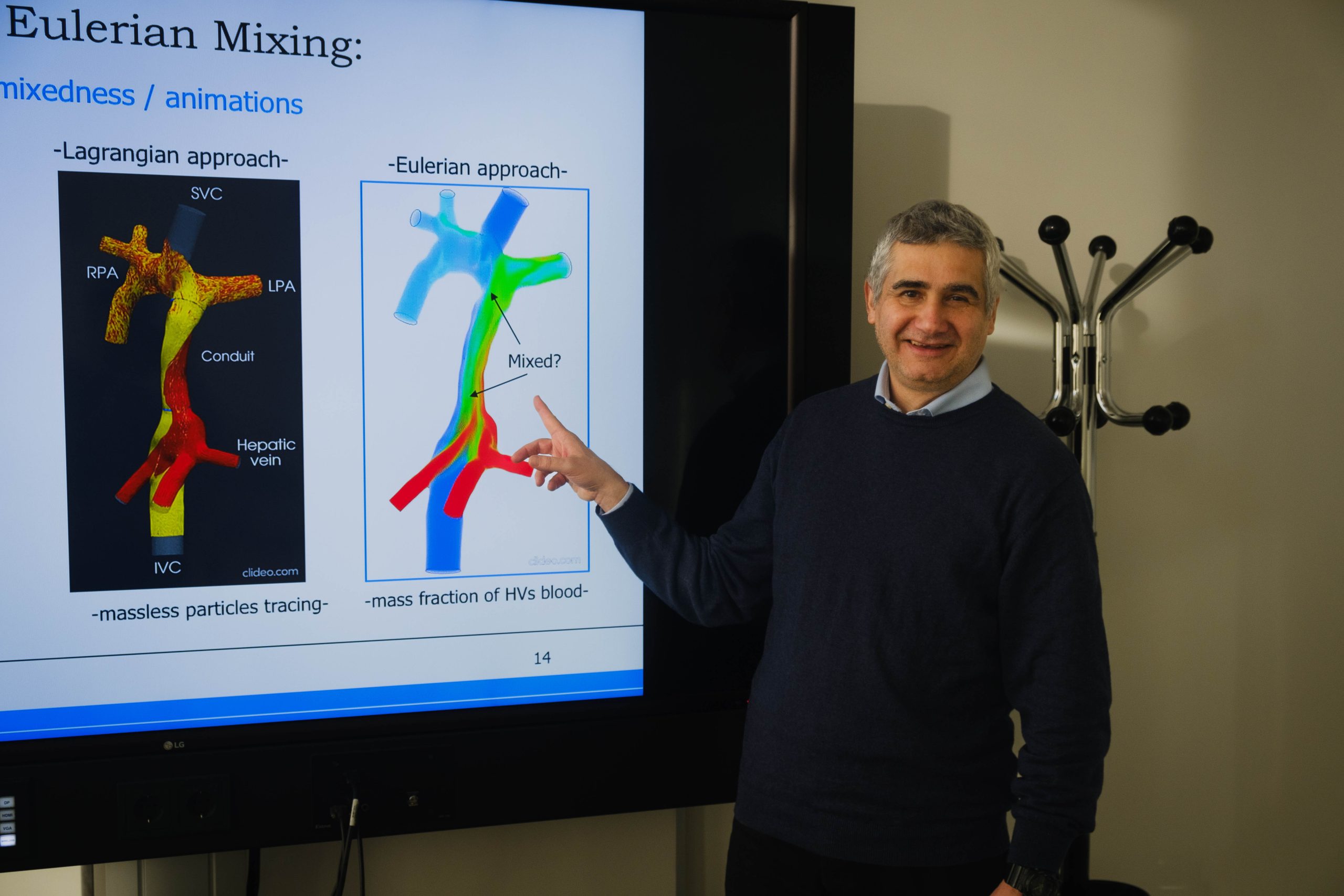

Dr Sasa Kenjeres (Applied Sciences) calculated the effect of the direct close connection between the body's arteries and the pulmonary arteries. Oxygen-poor blood is shown in blue, oxygen-rich with red. (Photo: Jaden Accord)

Sometimes a child comes into the world with a heart so deformed that only half of it actually functions. For the last 20 years or so, paediatric heart surgeons have fitted it with a GORE-TEX tube: a 16 millimetre wide implant directly connecting the lower vena cava and hepatic veins to the pulmonary artery, bypassing the heart.

Paediatric heart surgeons know that bypass or shunt as the Fontan procedure, named after the French surgeon who first performed the procedure back in 1968. Western countries currently have an average of about 70 patients per million population who have undergone that procedure.

The Fontan shunt allows deoxygenated blood to flow directly to the lungs, bypassing the heart. The only remaining ventricle pumps oxygenated blood from the lungs out into the body. This prevents oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood from mixing in the heart, which deteriorates the oxygen supply to the body. This is illustrated by the fact that after the Fontan procedure, usually at the age of two to four years, the child no longer looks blueish from bad perfusion.

Double circulation

A normal heart has two atria and two chambers or ventricles. The right half of that double circulation system pumps oxygen-poor blood from the body through the lungs. The more powerful left half of the heart pumps blood coming from the lungs out into the body.

Children who underwent a Fontan procedure, although saved from an early dead, are prone to complications and the consequences of weak circulation later in life, such as liver disease. Would they suffer fewer complications with a larger tube diameter, a team of (paediatric) heart surgeons from Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC) wondered.

Virtual surgery

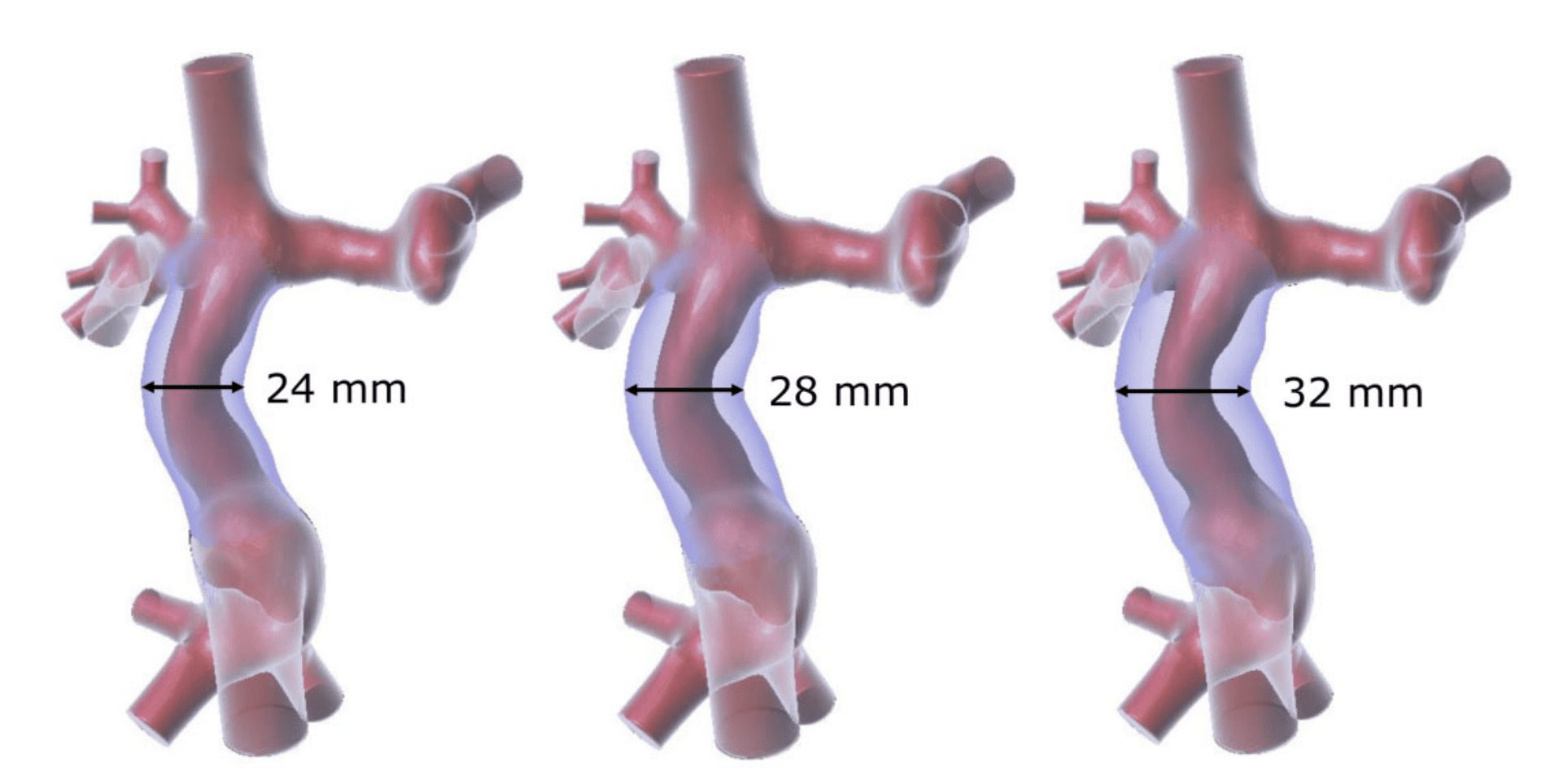

With this question in mind, flow expert Dr Sasa Kenjeres (Faculty of Applied Sciences) set to work with co-author Dr Friso Rijnberg and other cardiologists and paediatric cardiologists from LUMC. They decided on ‘virtual surgery’. What would happen if a 16 millimetre tube were replaced by one of 24 to 32 mm?

They tested this on the MRI images of five patients. In the computer, and not in the patient, they replaced a narrow tube with a wider one. Flow calculations showed a 40% to 65% improvement in flow, they write in Interdisciplinary CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery , a journal for cardiac surgeons.

Practical consequences

So, wouldn’t it be better to give these little children wider implants from the start? Paediatric heart surgeons are reluctant to to do so, says Dr Rijnberg. “Not only doesn’t a wider tube fit the anatomy of a child heart, but also the risk of formation of thrombosis (blood clots) increases in places where blood flow comes to a standstill.” Remember: a wider tube means a slower flow.

“For adults, the flow calculations are reassuring in that respect”, says Rijnberg. “Even when at rest and in the widest vessel, there is never more than 1.5% of the volume where stagnation occurs.” Which means little risk for thrombosis in adults.

Misjudgement

‘The Leiden team has demonstrated the unsuitability of narrow connections’ responds a team of paediatric heart surgeons from Washington in the journal. Dr Yves d’Udekem and colleages reveal that they reoperated on four Fontan patients last year to replace the narrow GORE-TEX tubes. They expect that eventually all of the patients with 14 or 16 millimetre implants will have top undergo an operation. They’re still in doubt what to do with patients who have received a 18 or 20 millimetre tube.

‘We misjudged the benefits of the Extracardiac Fontan procedure’ is their conclusion.

D’Udekem and colleagues are now considering other solutions such as a different surgical shunt (Lateral Tunnel Fontan) which has been known to grow along. Or using stretchable material so that the vessel can be dilated with a balloon over time.

- Delta has previously written about Kenjeres’ research on carotid artery flow in collaboration with the UMC Amsterdam.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.