The remarkable combination of silicon chips with beating heart muscle cells promises interesting applications, ranging from drug toxicity tests to self-powered implants, says professor Ronald Dekker.

‘Athlete drops dead at athletics meet’. Headlines like this are illustrative of what may well be the rare side-effects of apparently harmless pharmaceuticals, which can often be purchased prescription-free at drug stores. An infamous example is the first generation of histamine inhibitors, which are used to alleviate hay fever. As recently as last month, the Dutch physician’s magazine, Geneesmiddelenbulletin, cited the hay fever drug fexofenidine as having a disturbing influence on heart rhythm. The drug can make the heart beat dangerously slow. Nonetheless, this drug can still be purchased off the shelf as ‘STP-free’ or ‘Telfast’ in the Netherlands, although not in the United States.

Occurrences of lethal side-effects may be rare, but a drug that shows serious side-effects at some stage and then subsequently retreats off the market certainly isn’t. Dr. Stefan Braam, of the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), says that over the last 30 years some 28 percent of the drugs taken off the market had caused serious side-effects for the heart, including rhythm disturbances. “The pharmaceutical industry has set up special safety pharmacology labs where each new drug is extensively tested for cardiac by-effects”, Braam says.

These labs may soon profit from a new device, in which their products can be tested on actual living human heart cells. This device is currently under development at Pluriomics, a techno-starter, which has won the 2009 Netherlands Genomic Initiative Venture Challenge. Pluriomics is a joint initiative of the LUMC, a pharmaceutical industry partner, and professor Ronald Dekker, of the Dimes lab at the faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science (microelectronics & computer engineering).

Professor Dekker is mainly involved with the design of this device. The first prototype consists of a small array of contacts on the glass bottom of a tiny dish in which heart muscle cells are kept alive and kicking in a nutritious solution. Outside the dish, a selection of the contacts may be read out to record the electrical activity of the heart muscle cells. Add some drug with known a side-effect and one can actually see the repolarisation of the heart muscle cells slow down, which in a real heart manifests itself as disturbances of the heart rhythm. “The principles works”, says Dekker, who is quick to point out that selecting and growing the right heart cells is crucial for the device’s success.

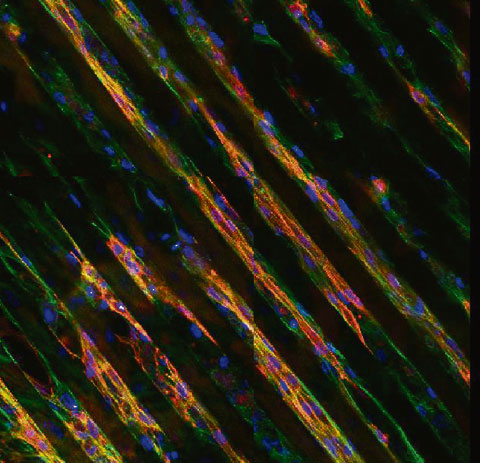

Braam, who completed his PhD under the supervision of stem cell expert professor Christine Mummery in Leiden, is responsible for the cell cultures. He explains that skin cells can be reprogrammed into stem cells by adding three genes crucial in early foetal development. Stem cells can be persuaded under the right conditions to grow out into contracting lumps of heart muscle cells, which must then be eased apart in order to line them up on the test chip.

Being able to make stem cells from adult specialised cells is an important step. By taking tissue from someone who is known to have suffered the cardiac side-effects, the researchers are confident that the cultured tissue will be sensitive to the side-effects.

Dekker and Braam estimate that they will need another three to four months before they can present their prototype drug tester. Meanwhile the design is being improved to best accommodate the heart cells. “The cells get stressed when they are mounted on rigid glass”, Braam explains. So now the researchers are experimenting with a softer and more flexible substrate, which can be stretched periodically (by air pressure) to mimic the beating heart tissue.

For Dekker, the fun has only just begun. He likes to fantasise about the possible combination of micro electrical or mechanical devices and living cells. One of his favourites is a dynamo driven by one’s own heart muscle cells. Such a bio-battery could be used to power implants, like drug pumps or pacemakers. And it would never need to be replaced. A lifetime guarantee.

De War on Terrorism in de Verenigde Staten is anno 2009 wereldwijd bekend. In de film ‘Public Enemies’ zien we een War on Crime die ruim tachtig jaar eerder plaatsvond. Deze oorlog werd gevoerd tegen de gang van John Herbert Dillinger. Deze beheerste in 1933 en 1934 de media in Amerika. De film is gebaseerd op het non-fictie boek van Bryan Burrough en geeft een mooi tijdsbeeld van de dertiger jaren in de Verenigde Staten.

Tijdens de depressie schrikt Amerika op door de opvallende bankovervallen van John Dillinger. Door zijn charisma en ogenschijnlijk gemakkelijke ontsnappingen uit iedere gevangenis groeit hij al snel uit tot een volksheld. Het onschadelijk maken van Dillinger wordt de prioriteit van Edgar Hoover en Melvin Purvis, twee topagenten van de net opgerichte FBI. Zij roepen Dillinger uit tot Public Enemy Number One. Door zijn gevangenneming hopen Hoover en Purvis dat de FBI zal uitgroeien tot de nationale politiekracht die het nu inmiddels is. Er wordt een gigantische politiemacht op de zaak gezet, maar Dillinger laat zich niet zonder slag of stoot gevangen zetten.

Regisseur Michael Mann kon rekenen op een bezetting met grote namen, waaronder Johnny Depp (‘Pirates of the Caribbean’), Christian Bale (‘The Dark Knight’) en Marion Cotillard (Acedamy Award voor haar rol in ‘La Vie en Rose’). Dit geluk had hij voornamelijk doordat andere projecten van deze acteurs tijdens de schrijversstakingen in Hollywood stil lagen. Met deze ijzersterke crew weet Mann een overtuigend tijdsbeeld te schetsen van de crisisjaren in de Verenigde Staten. De acteurs, kleding, het decor en de aankleding zorgen dan ook dat de film, naast actiethriller, een sfeervol historisch verhaal is. Public Enemies ging op 2 juli in première en draait in Delft in Mustsee. Kijk voor aanvangstijden op de website van de bioscoop.

Comments are closed.