The shipping industry needs to be less polluting and even become emission free. How can this be achieved at a time where everyone orders everything from Temu? By falling back on the wind. Researchers are testing the aerodynamics of a cargo ship in a wind tunnel to determine the best place to position rotor sails.

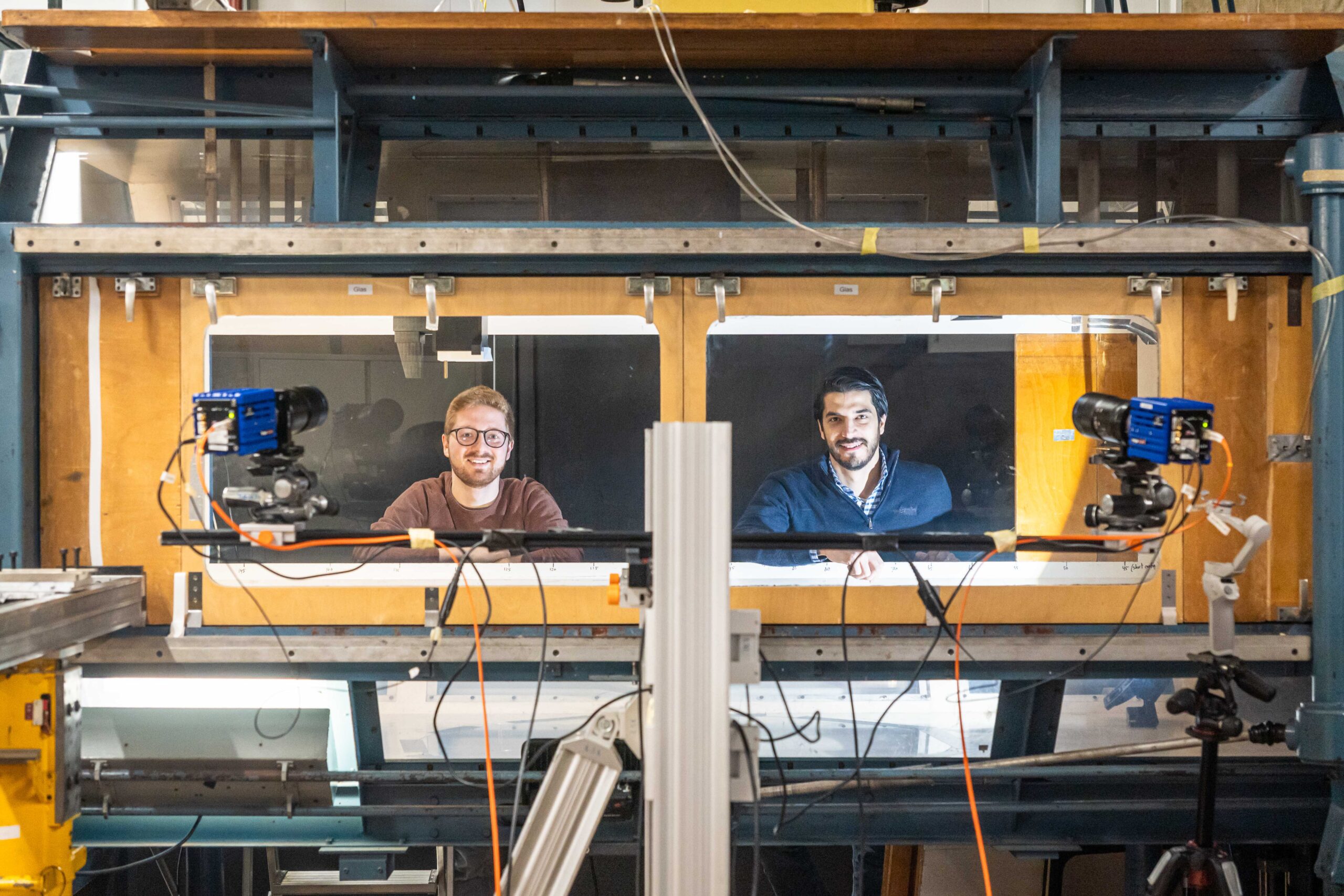

Hendrik Fischer (left) and Alberto Felipe Rius-Vidales at the wind tunnel. (Photo: Thijs van Reeuwijk)

This article in 1 minute

- Maritime shipping must become far more sustainable; sailing at lower speeds and making use of wind can significantly reduce emissions.

-

Delta was there when TU Delft researchers tested how air flows around cargo ships in a special wind tunnel, with the aim of optimizing wind propulsion.

-

Using mist particles, lasers, and cameras, they precisely measure the aerodynamics of a ship model and determine where mechanical sails can be placed most effectively.

-

Their research focuses in particular on rotor sails: rotating columns that generate additional thrust through the Magnus effect.

-

In addition to rotor sails, there are also rigid wings, suction sails, and kites, each with its own advantages and disadvantages depending on the vessel and its route.

-

In the future, ships and shipping routes will be designed more around wind conditions; wind can already save about 15% in fuel consumption and could potentially increase to 50%. Provided that longer travel times are acceptable, fully wind-powered shipping is of course also possible.

“Nothing is as green as decreasing the knots”, says Albert Rijkens (Mechanical Engineering), a maritime researcher. For those who know nothing about sailing, this means sailing slower as the speed on water is expressed in knots. And sailing more slowly means less emission, explains Dr Albert Rijkens. His WASP research falls under both Mechanical Engineering and Aerospace Engineering.

This may sound odd as you probably do not immediately make the link between shipping and aviation and aerospace technology, yet this is precisely what is being researched on this December day in the wind tunnel at TU Delft – the role of air flows on cargo vessels. This is because wind can make shipping more environmentally friendly by using sails, as has been done for centuries. However, these would be a special type of sail: mechanical sails.

The wind tunnel takes up several floors

We are at TU Delft’s Low-Speed Laboratory. Rijkens says that it is a unique facility as the entire building was designed around the Low Turbulence Tunnel (LTT). The wind tunnel takes up several floors and is made of concrete.

Dr Alberto Felipe Rius-Vidales, Aerodynamics Research Lead at the Wind Thrust Research Program explains that “Its construction makes the tunnel’s air flow quality highly suitable for aerodynamic research and we are happy that we have this facility in house at TU Delft.” He points around. “The ventilator is on the ground floor. The air flows three floors up, passes a few anti-turbulence screens, then passes through a narrower channel and enters the test area. This creates a uniform air flow where we can test things like the aerodynamics of cargo ships or a sail system.”

Droplets of mist measure the air flow

A cargo ship is on the programme today. Hendrik Fischer, a doctoral candidate, turns a screw and the set-up to test the aerodynamics of the cargo vessel model is ready for use. “Activate airflow seeding system,” says Fischer. He presses a button and mist blows into the wind tunnel. Rijkens makes a comparison: “It’s just like the smoke from a smoke machine in a disco.”

Lights out, safety glasses on, laser on. The laser gives two short consecutive pulses that light up the droplets of mist in a vertical plane. Two cameras take photos. “This allows us to identify the average movement of the droplets,” explains Rius-Vidales. “And because the small microscopic droplets move with the air flow, we can assess the velocity of the air flow very accurately.”

‘Measuring with rotor sails. That brings all sorts of challenges’

The data flows onto the computer screens. The left screen shows the pressure on the side walls of the wind tunnel. They need to correct for this since there are actually no side walls. The right screen shows an image with the ‘velocity field’. The particles are not affected in the red area and can flow without disruption. Blue means a lower or even negative velocity – movement against the flow. “Not bad,” says Fischer when he has a first look at the data. “It’s going very smoothly so far.”

Modern version of sailing

The purpose of the test is to clearly understand the aerodynamics of the ship so that they know where the rotors should be placed. The rotor sails are high rotating pillars that spin in the wind and generate aerodynamic power according to the Magnus effect. This effect gives the ship greater momentum. It is the modern version of the usual sails of a sailing boat. Why not just add normal sails? “These are such heavy ships that you would need enormous sails,” explains Rijkens. “It would be very cumbersome to sail.”

The first round of measuring 50 velocity fields is done. Given the measurements, can Fischer say anything about where the rotors should be fixed on the deck? “We need a lot of measurements. In the end, we will have a map with the best position. I cannot say much about it now, except that you want to stay away from the places where the air flow seperates.” He points to the white and blue areas in the image.

Scaling velocities

What are the next steps? “Measuring with rotor sails. That brings all sorts of challenges”, says Fischer. He gives a mini-lecture about velocity scales. The rotors on the ship need to spin, about 200 revolutions per minute, but in this miniature version that becomes 8,000. “When the velocity heads towards the speed of sound, the air is somewhat compressed which can lead to all sorts of undesirable effects.” To handle this well, the researchers will have to move to a different kind of wind tunnel where they can control the air pressure to carry out their measurements.

Once the cargo vessels with rotor sails are tested, it is time for a new round of measurements. “We are currently working with existing ships, which are like huge blocks where the aerodynamics were absolutely not taken into account,” says Rius-Vidales. “We will soon test aerodynamic ships that are specially designed to have rotors added. I’m looking forward to this. There will definitely be surprises.”

Different types of mechanical sails

There are currently about 80 ships in the world with wind propulsion. “My estimate is that 40% of them have rotors, 40% use suction sails and the remaining 20% sail with other kinds of sail systems,” says Rijkens. This calls for some explanation:

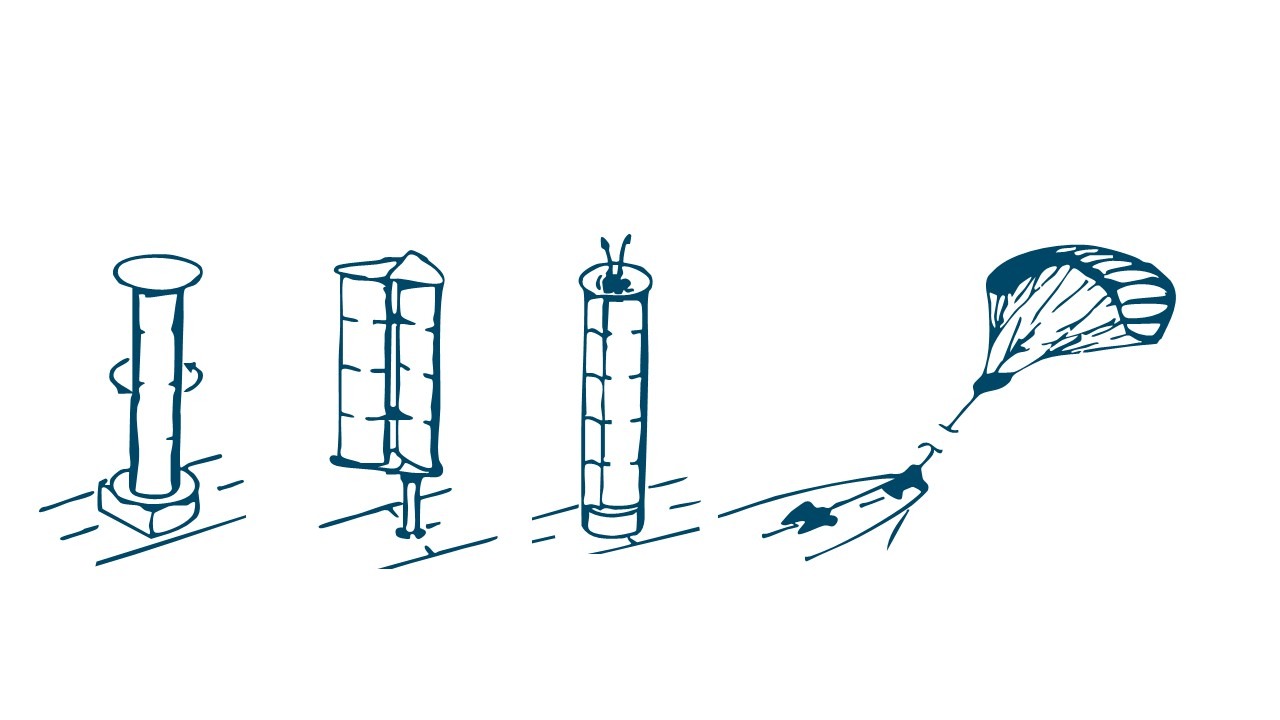

- Rotor sails. Upright pillars that rotate. If the wind flows around the rotors, the rotation creates a difference in pressure on both sides of the rotor. This generates aerodynamic power that moves the vessel forward. “The rotors that we work with are often 28 metres tall and have a diameter of five metres.”

- Rigid wings. Fixed wings comparable to aeroplane wings. In this case the shape of the cross-section of the wing – the wing profile – creates pressure differences which moves the vessel forward. Disadvantage: the wings are huge, even a lot higher than a rotor sail, and are very much bigger in terms of area. “This creates additional challenges during operation.”

- Suction sails. Ventilated wings. These involve thick wing profiles to generate major aerodynamic power. Given the thicker profile, ventilators need to be installed in the wings that suck air from the passing air flow on the surface of the wing so that the boundary layer does not get released. This combination means that more power can be generated according to the surface area of the wing than with the conventional rigid wing.

- Enormous kites that need to be opened and closed under control. Advantage: flexible and fewer material costs. Disadvantage: if the kite falls into the water it cannot be used anymore. This makes it somewhat more vulnerable. Furthermore, kites are only useful if the wind blows from the rear which is rare as ships have their own forward moving momentum.

The future of the maritime industry

What will shipping be like in the future if wind plays a bigger role? “Not only the shape of ships will change, but also the shipping lanes,” says Rijkens. “They now go for the shortest route, but later will go for the most advantageous route in terms of wind. This is continually changing. Better weather models are allowing them to predict this better.”

‘They now go for the shortest route, but later will go for the most advantageous route in terms of wind’

And this is not the only aspect. Rijkens explains that the performance of different types of sails depend on the angle that the wind comes from. “The poles have different prevailing winds than the equator. Ships often sail a set route. So depending on the route that a ship takes, different sail systems will be used.”

“We now achieve about a 15% saving when using sails. If we improve all the associated systems, we will achieve up to 50% and maybe even more. One hundred percent may of course be possible,” says Rijkens cautiously. “But this will mean that it will take longer before you receive your order.”

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

E.Heinsman@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.