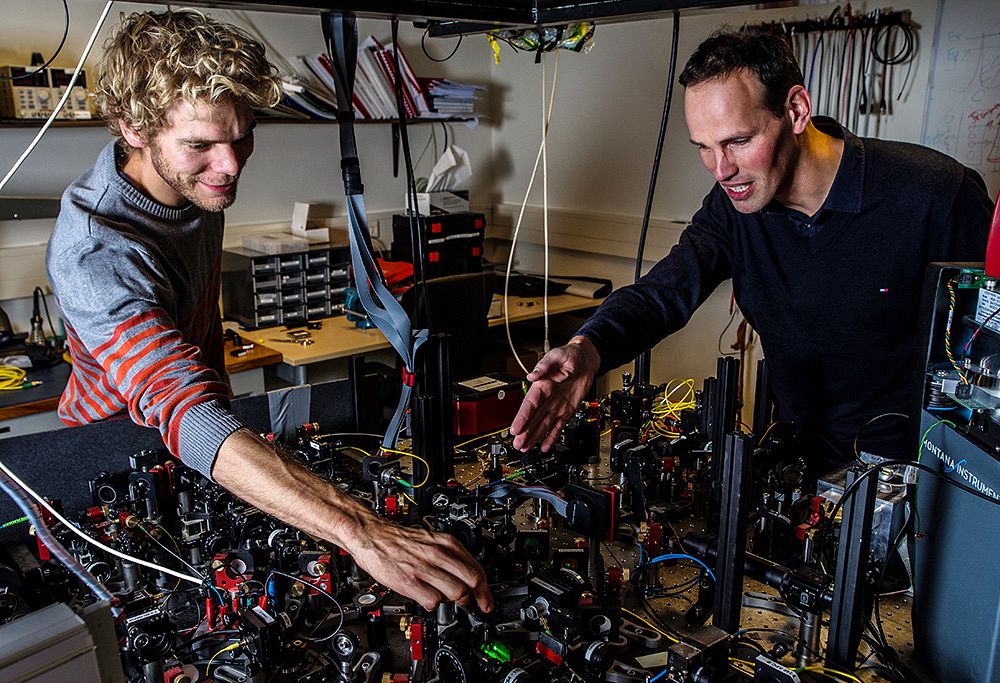

Surely, two distant objects cannot influence each other without communicating, right? Ronald Hanson and his team showed that this view of nature is outdated. Their publication in Nature asserts the reality of quantum weirdness.

Their experiment works with two electrons at a large (1.3 km) distance which are entangled with a clever trick. A partially transparent mirror entangles two photons that are themselves entangled with the distant electrons. Once the electrons are retroactively entangled, they can be used in a quiz-like experiment called the Bell-test. Due to the entanglement, the measurements of the photons coming from the distant electrons (as ‘answers to the quiz questions’) will be strongly correlated. In an earlier article, Delta covered the experiment in more detail.

The statistics of the measurements should reveal whether or not the electron spins show more coherence than could be anticipated by chance. Last year, Delta published an article to explain the experiment from the start.

In its latest publication in Nature, the team writes just a few entanglements happened every hour. So for their 245 measurements to occur, it was quite a wait.

The result means that entanglement at a distance is real. Or, as Hanson explained at the presentation of his experiment last year, “As soon as you perform a measurement, that determines the state of each particle. No communication is necessary to achieve this: the effect is instantaneous. You just have to dare to let go of the idea of locality.”

The result impresses colleagues from science, but it doesn’t surprise them. They are used to the quantum weirdness of nature, but so far no one has proven the point so concretely. The Australian physicist Howard Wiseman said in Science that the experiment is “a milestone in quantum physics”. The Austrian teleportation expert Anton Zeilinger called the experiment in Nature “ingenious and beautiful”.

The most probable application of firm and proven entanglement at a distance could be an unhackable internet. “Entangled particles sent over such a network would be protected against hackers; an eavesdropper could not tap into the information without making her presence known”.

Read this article: Einstein proved wrong

Comments are closed.