The zoekjaar offers international graduates a chance, but at a price: one year of relatively low professional wages.

Often after the completion of their MSc programmes, many international students want professional experience, seeking to work in the Netherlands.

But non-EU citizens are not automatically granted permission to work here without first possessing EU work permits. This is when the so-called ‘zoekjaar’ (or ‘search year’) comes into play.

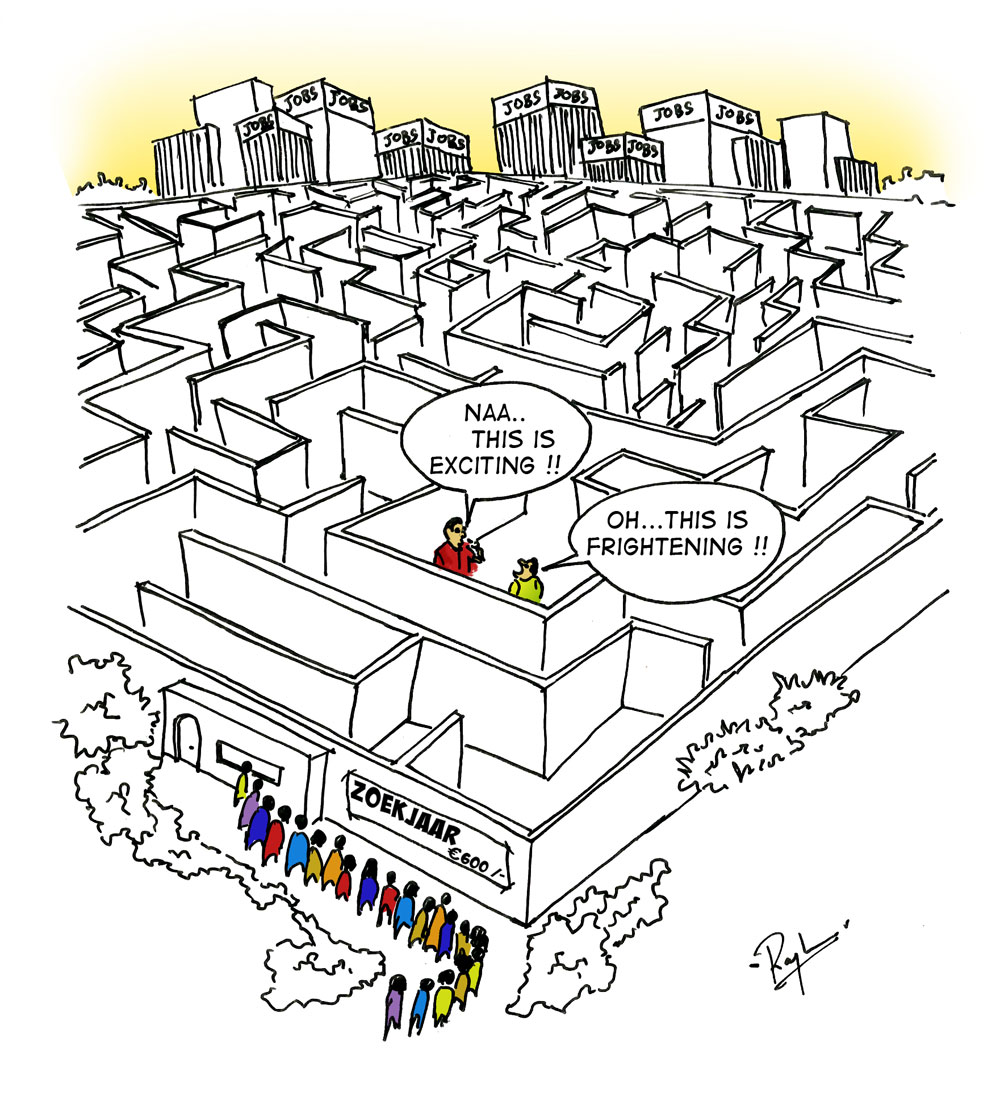

The Dutch government grants search year visas to non-EU international students who have completed higher education studies, allowing them to stay and search for jobs in Netherlands for one year after graduating. Many students apply for search years and then look for jobs or internships, with some finding the search year experience easy, while others struggle to land dream jobs.

Ajith Sridharan, an Indian and recent graduate of faculty of Aerospace Engineering, is currently in his search year, which he thinks is a win-win situation for students and employers, as students looking to acquire new skills benefit, as do employers looking to save money through cheap labour. Sridharan says he’s working to gain experience and build his skills, so he doesn’t care if employers take advantage of the situation, adding that if he continues working in the same firm, he will ask for a valid compensation accordingly.

For Chandra Pudiatje, a Industrial Design Engineering graduate, the search year experience was a mixture of worries and hopes, faith and support. The Dutch company she worked for during the search year helped her get her kennismigrant (foreign resident) visa from IND. Pudiatje was working as an independent consultant, which she enjoyed, and for which she was remunerated at a standard daily rate. When there was a vacancy in the company she applied, but before she could be officially hired her search year tenure ended. She was having trouble with the IND regarding her foreign resident visa, but fortunately her company came to the rescue and she was granted her foreign resident status.

Due to Dutch laws, it’s easier and more profitable for companies to hire international students with search year status than to hire international staff from outside Netherlands. Companies have to pay minimum of 26,000 euros annually when hiring students with search year status, but considerably more when hiring international staff from abroad.

Sumit Sachdeva, a biochemical engineer and now PhD candidate, says that even though the job application process takes time, search year provides enough time to find decent jobs. But at times companies do seem to exploit the search year status of the students. Companies try to hire students through consultancies instead of hiring directly, and these consultancies hire students for maximum one-year contracts.

Some students, like Novi Rehman, utilise the search year to gain higher ground. Rehman, a 2010 graduate from Indonesian, used her search year to bridge the gap between her graduation and waiting for her German work permit to be approved. Having a search year visa made her transition less complicated.

While some graduates have negative search year experiences, Rehman believes the search year still works as a “ticket” to stay and land work in Europe. It’s a choice to make: if you take search year, the possibility is 50-50, but if you don’t, it’s zero.

Comments are closed.