Universities do not really know what their patents are worth, a Groningen emeritus argued in the FD. TU Delft is a leader in patents, but what is the value?

Ronald Gelderblom (director Delft Enterprises) speaking with Adriaan van Noord, head of IP with I&IC. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

The Dutch FD newspaper published an article by Gerard van Beynum, Emeritus Professor of Biotechnology, who wrote that universities often dispose of their patents too cheaply and lose money as a result. What do TU Delft experts think of this statement?

Delta asked the two TU Delft patent guardians, Adriaan van Noord, Head of Intellectual Property (IP) at the Innovation & Impact Centre (I&IC, formerly the Valorisation Centre) and Ronald Gelderblom, Director at Delft Enterprises, the TU Delft company that helps TU Delft spin-offs get started. Spin-offs are start-ups related to university patents.

‘People are quick to think of profit maximisation, but that is not the goal of universities’

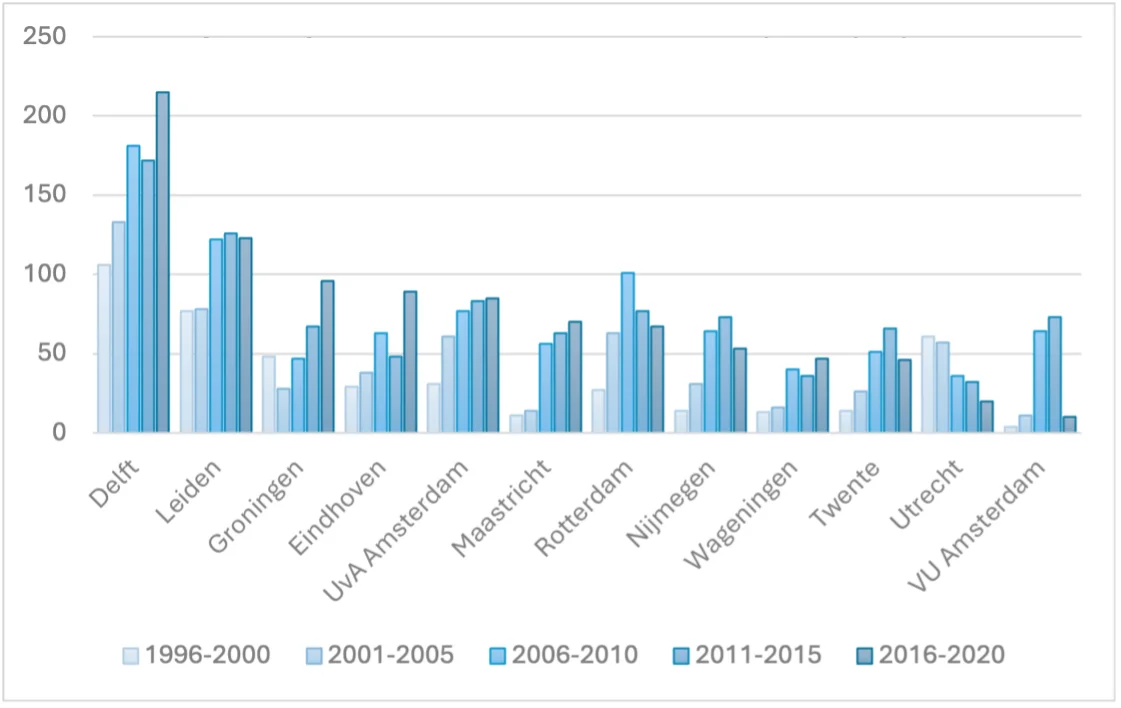

Number of patent applications per university

Million euro business

First some figures. TU Delft leads the patent field among Dutch universities with more than 50 applications a year.

With eight staff members, I&IC manages some 300 patents worldwide. According to the Annual Report 2023 (only in Dutch at the moment) revenues on patents and licences amounted to just under EUR 1 million .

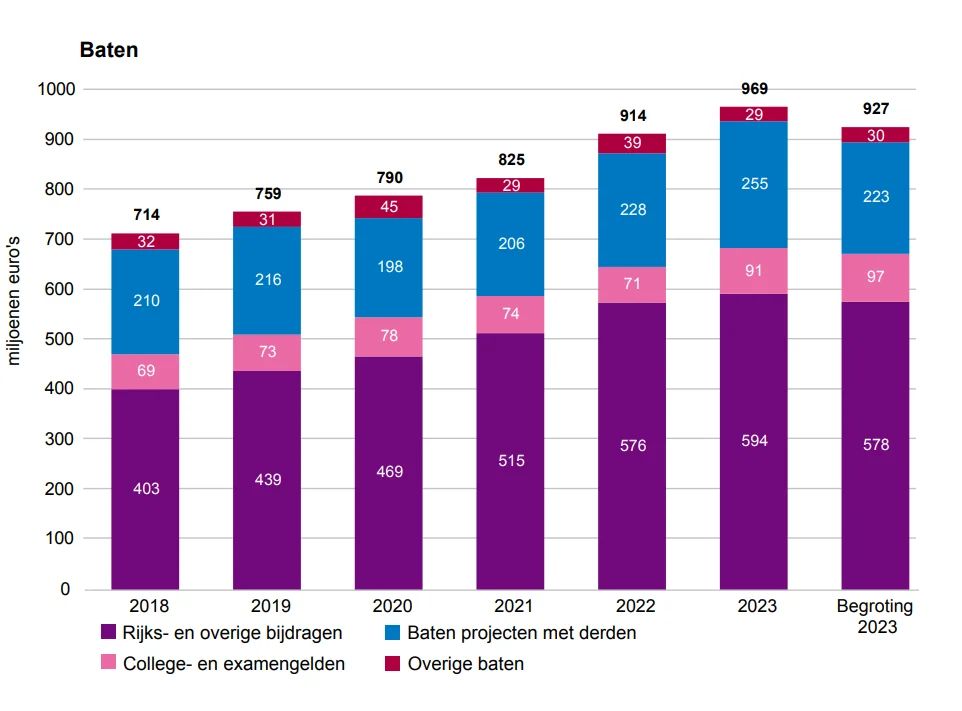

Delft Enterprises employs 13 people and has stakes in about 70 TU Delft spin-offs. The private equity firm’s income consists of increasing share values. in spin-offs and from acquisitions by businesses. The amount this generates is not clear, partly because the amounts involved in takeovers are often confidential, and partly because revenues vary quite a bit from year to year. Delft Enterprises’ revenues are not listed separately in the annual report, but are included in the ‘companies’ item under ‘income from projects with third parties’. That item amounted to EUR 57.4 million in 2023, but only part of it came from Delft Enterprises.

Income TU Delft 2023

What do you think about the assumption that universities do not have a good idea of the value of a patent?

Adriaan van Noord: “Well, I think we do have a good idea of the value. But what is value? People quickly think of profit maximisation, but that is not the goal of universities. TU Delft strives to create social impact. Patents are not an end in themselves, but a means to achieve impact. The highest bidder is sometimes a company that wants to keep a disruptive new technology off the market to safeguard its own interests. If you choose to do that, profit maximisation comes at the expense of impact.”

Creating impact often runs through companies. Is that the course of action?

Ronald Gelderblom: “There are two routes. You can either make the IP available to existing companies, or you can introduce it to the market through a new company. I&IC provides the route to existing companies. Delft Enterprises guides spin-offs. Historically, there are eight to 10 spin-offs a year.”

Are there any familiar names among them?

Gelderblom: “We have had a few profitable exits in recent years – spin-offs that were bought up by other companies. Mayht, which was sold to Sonos for EUR 92 million, is a great example. MILabs was acquired by a Japanese industry peer. And the Blue Phoenix Group, with a patent from Recycling Professor Peter Rem, extracts metals and minerals from the ashes of waste incinerators. The income from these acquisitions is shared equally between the inventors, their departments and us.”

‘TU Delft sees a patent as a means of ensuring that university knowledge is applied in practice’

Van Beynum thinks that universities should set up a company to determine the value of patents. What is your view on that?

Van Noord: “The things that are developed at universities are often no more than inventions with potential that still need a lot of work. How do you value these? The costs play a role, but also what the patent may deliver and how much it still costs to get there. TU Delft sees patents as a means of applying university knowledge in practice. Sometimes, the best route is for an existing company to apply for the patent directly; at other times, if we have a disruption to facilitate, we will go to Delft Enterprises to see if a spin-off wants to get involved.”

Gelderblom: “There are three ways to earn from a patent. You can sell it for a one-off fee. Or you can licence it – the company then pays royalties. You can also place the IP in a start-up where TU Delft takes shares in the company. This is often TU Delft’s preference, especially if it remains involved in the technical developments.”

‘The number of assumptions increases when the so-called technology readiness level is lower’

Van Noord: “With sound business and legal agreements, we ensure that TU Delft shares in the success. An immediate valuation is only necessary for a one-off sale. With spin-offs, it’s about royalty or equity deals.”

How does a one-off valuation come about?

Van Noord: “The valuation of intellectual property is not an exact science, but an estimate. There are three common approaches based on cost, market or revenue. In the first method, you look at the costs incurred to generate the IP. For this, we use the internal TU Delft Guide to Intellectual Property. This is particularly useful when making agreements before the IP is created, such as for research contracts. The second method, market-based, draws on industry standards and comparable transactions. Organisations such as the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) give ranges of royalties that are common in a given industry. The third method relies on cashing in on expected future revenues. The number of assumptions involved increases when the so-called technology readiness level is lower. And because university patents are often far from the actual application of the item, universities rarely base valuation on expected revenues. Instead, TU Delft prefers to become a shareholder through Delft Enterprises. In short, we work within frameworks that take the specifics of university IP into account.”

How many shares does TU Delft take in companies?

Gelderblom: “That varies from 10% for software that has a temporary competitive advantage to 25% for a rock-solid indispensable patent. We laid down the rules for this in so-called ‘deal terms’ that became the standard for all universities last year. So cooperation between universities is already there, just not in the form of a company, but under the banner of Universiteiten van Nederland (UNL, Universities of the Netherlands).”

Help, I made an invention

In their employment contracts, employees of TU Delft, including PhD students, have a duty to disclose their intellectual property when a patent is published. An ‘invention disclosure form’ (IDF) records who is involved in the patent. Any income from the patent, after deduction of costs, is divided in three equal parts among the patent holder/holders, their department and I&IC.

Students are not employed by TU Delft and therefore own their own IP. If they want to set up a company and use it, they can find advice on IP and entrepreneurship on TU Delft’s website.

- Read more: TU Delft’s patent portfolio with more than 3,000 inventions

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.