The mathematical achievements of Dutch secondary school pupils never dropped as strongly as between 2018 and 2022. TU Delft mathematics teacher, Tom Vroegrijk, believes that universities should take measures to still give them a chance.

(Photo: Justyna Botor)

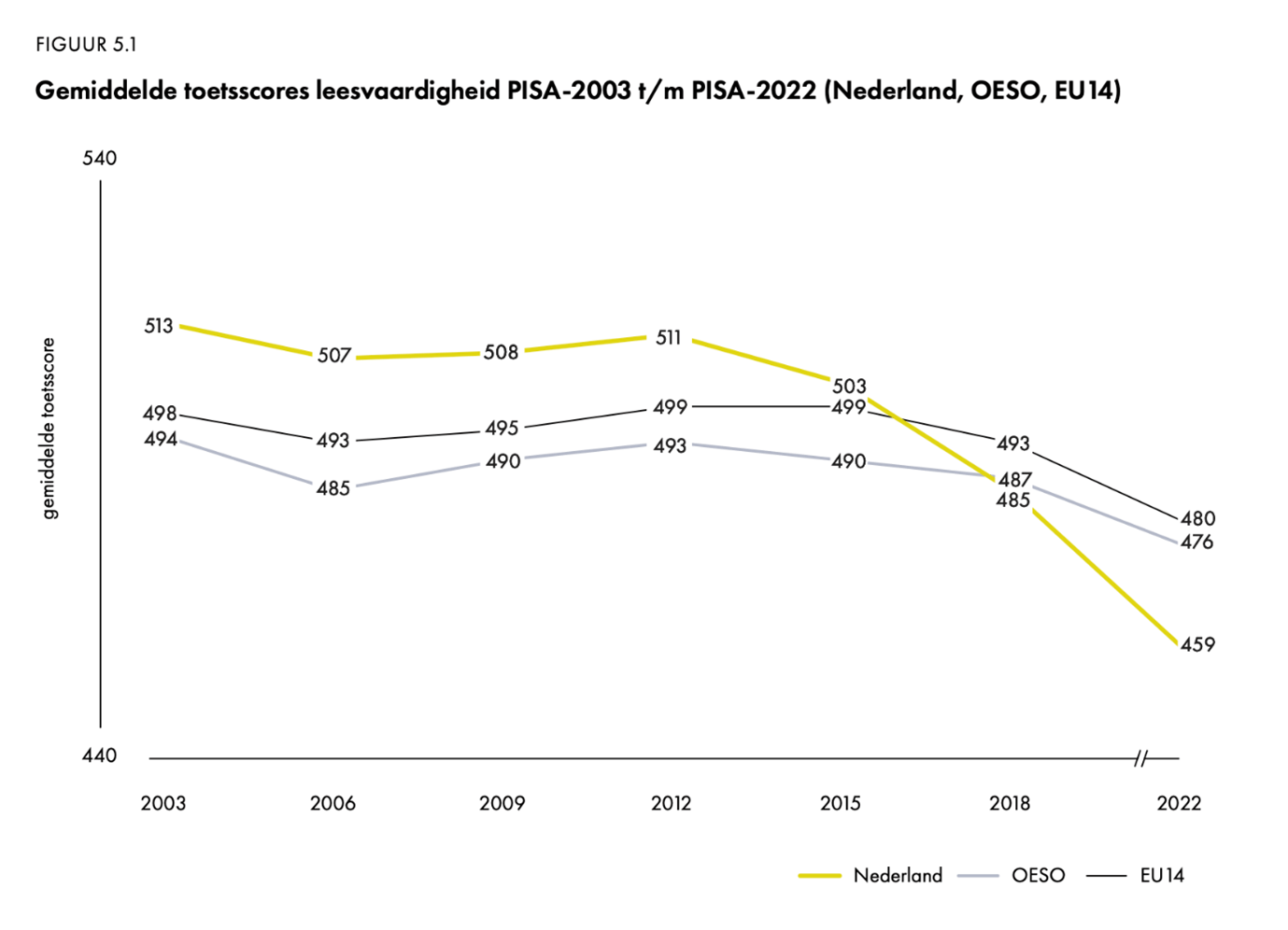

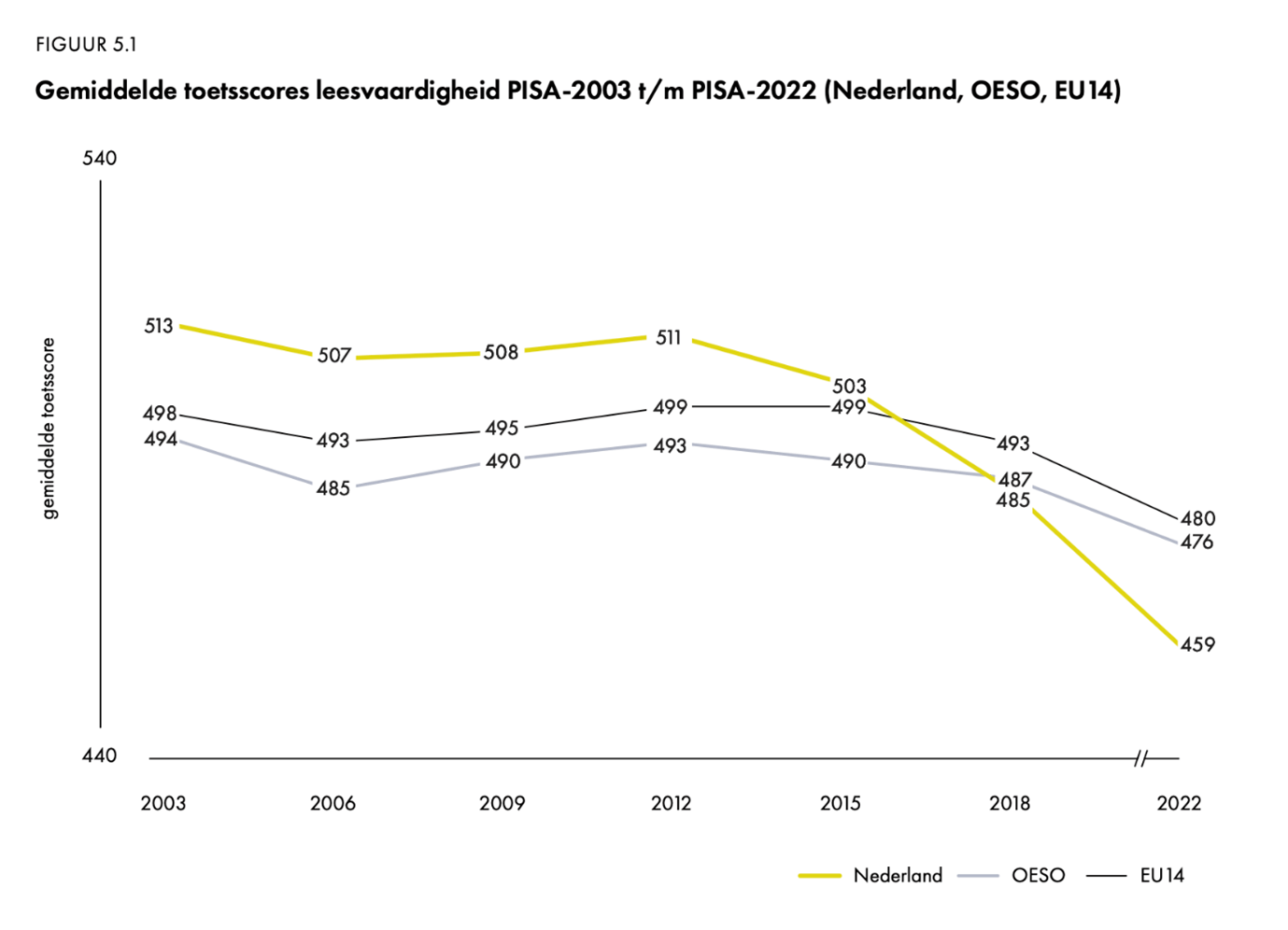

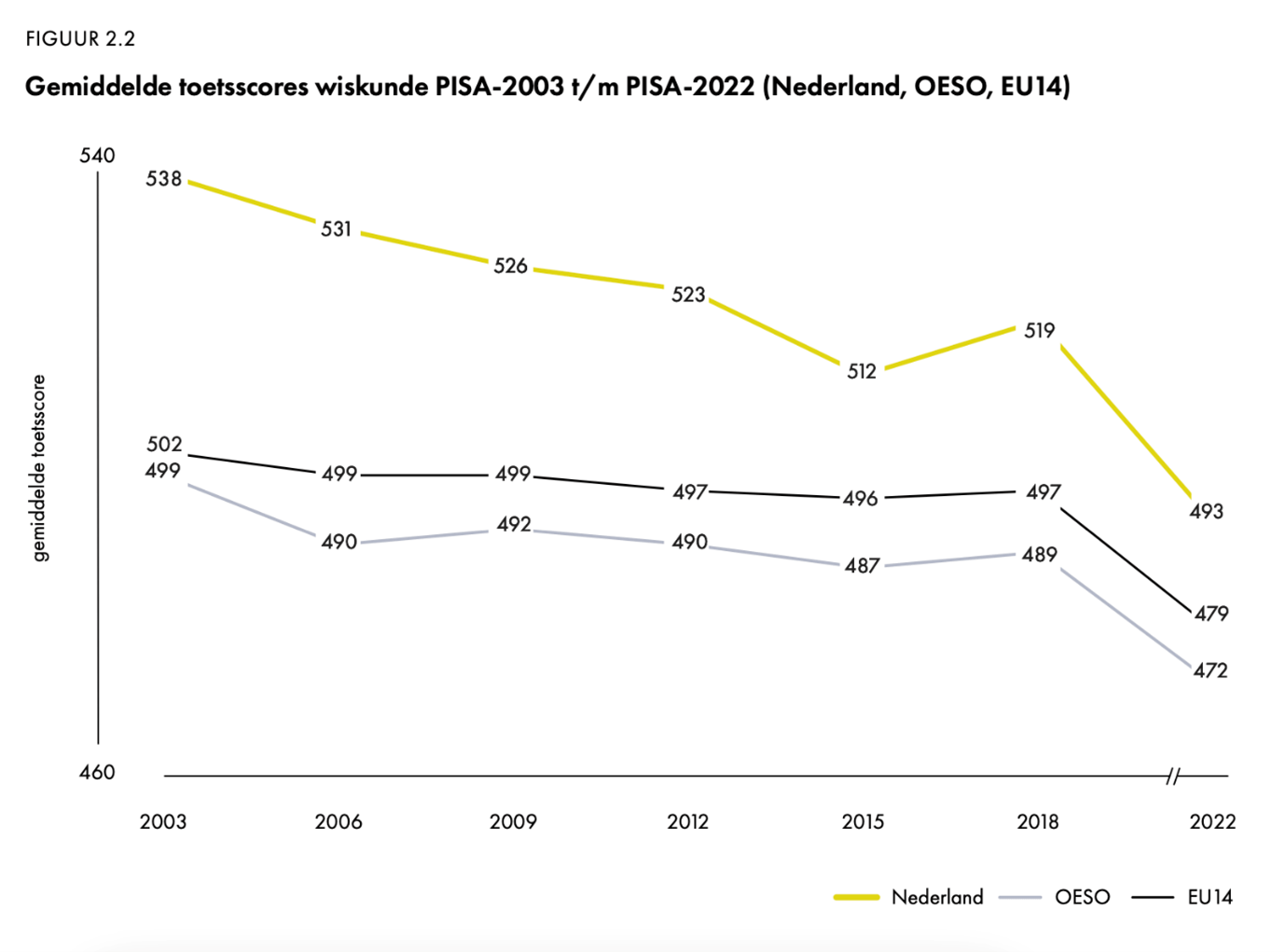

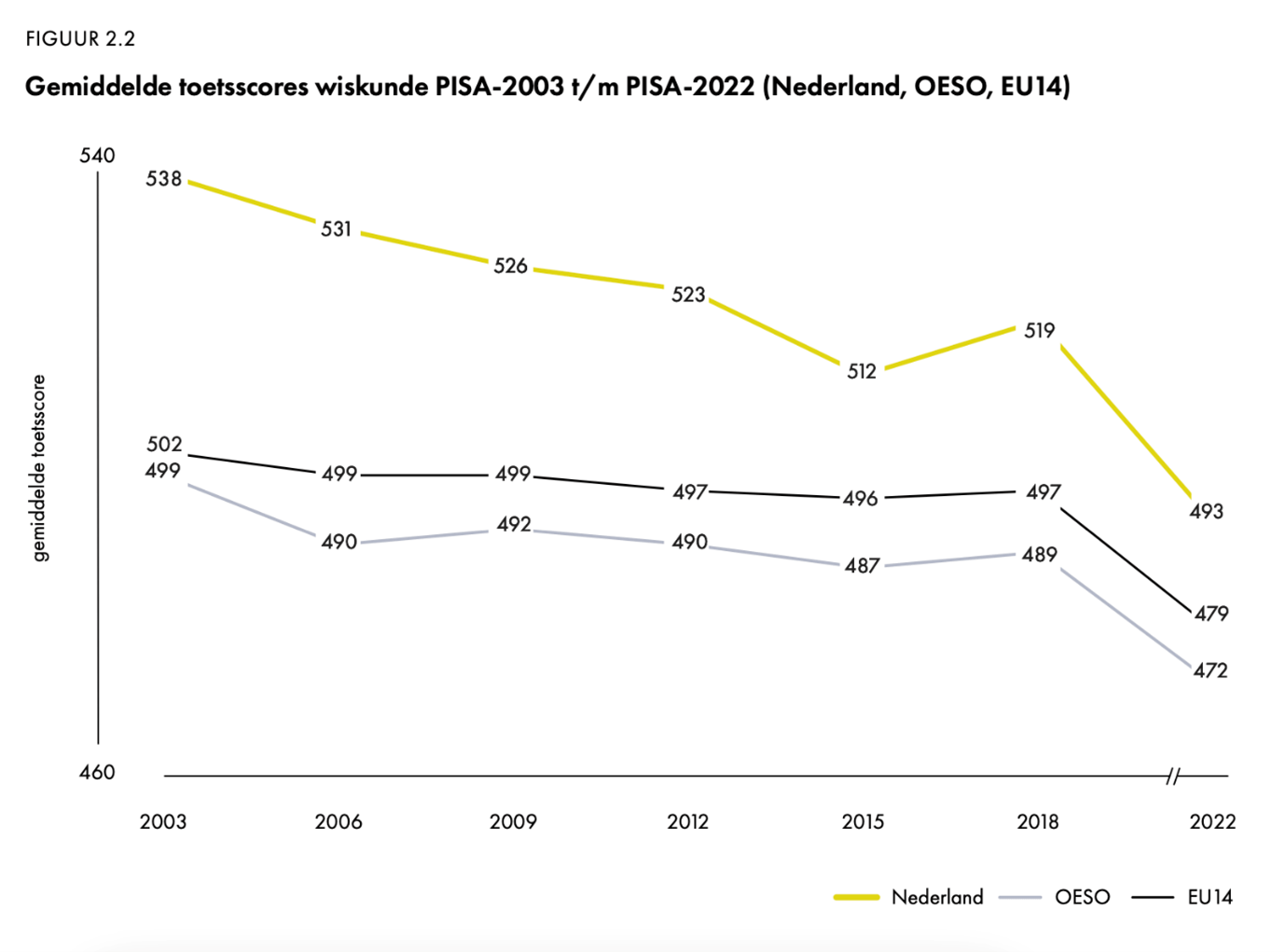

Every three years the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) runs a major international survey of the reading skills and mathematical and natural sciences knowledge of 15 year olds. In 2022, the focus of this research was on the field of mathematics. The results of this Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) were published recently.

The outcomes of the PISA-2022 show that the performance of pupils in the Netherlands and Flanders in mathematics are dropping radically. The Netherlands even saw the largest drop in scores for mathematical literacy ever.

In Flanders, the average achievement for mathematics between 2003 and 2022 dropped by 52 points. In this same period, the OECD average dropped by 22 points.

Literacy skills are even worse. In Flanders, 24% of 15 year olds do not have the skills that PISA believes pupils should have to be able to do well at school and in society. In the Netherlands this is even 33%. The literacy skills score of Dutch pupils in PISA-2022 is even lower than the OECD average.

After the PISA report was published, there was no lack of reactions to the state of secondary education and the problems that it is facing – just think about the shortage of teachers. However, noticeably absent in the discussion were the universities of applied sciences and universities.

Academic voices

I argue that this issue really does affect us, and that academics should have their voices heard much more strongly. The pupils described in the PISA report are, after all, the young people who will enter our academic institutions as new students in a few years’ time.

Large groups of students with an inadequate prior education are likely to take a seat in our lecture halls in the years to come. If we do not keep this in mind, we both risk an increase in the dropout rate and we ignore huge talent potential.

‘First years should be given more leeway in failing’

The three proposals below may help give future talent the opportunities they need to develop themselves to their full potential despite their inadequate prior education.

Quality of education

One, even more attention needs to be paid to the quality of education. My initial thoughts are for a more intensive supervision of new teachers. Much is now known about teaching practices that have a positive learning effect. One example is Rosenshine’s Ten Principles of Instruction.

So let’s make sure that new teachers are fully versed in these didactic principles and let’s support them where necessary.

Furthermore, we should do even more to facilitate the sharing of experiences between faculties. In doing so, we will create a lively and blossoming teaching community at TU Delft.

Remediation

My second proposal is that we make remediation compulsory for first year students that are not making the grade. I see plenty of good initiatives such as summer schools and extra lessons, though they are mostly optional and not compulsory. The students who most need extra help thus do not take the opportunity they provide.

A number of degree programmes in the Flemish higher education system use a positioning test. Students do the test before the start of the new academic year. Anyone not achieving the required score may be obliged to take remedial classes.

BSA

And finally, my third proposal is that I believe that first years should be given more leeway in failing. I think the current BSA (binding recommendation on continuation of studies) ruling is too strict. At the start of the academic year, new students regularly fail tests as they are still getting used to the academic level and the speed of teaching at universities. Once they fall behind, they are often unable to catch up.

Given the trend of the worsening performance in maths among pupils in the Netherlands and in a lot of other European countries, it is highly conceivable that the divide between secondary and higher education will only get wider in the next few years. Given these circumstances, should we continue forcing students who do not get the required 45 credits to stop their degree programme?

Tom Vroegrijk is a mathematics teacher and Programme Manager for the Programme for Innovation in Mathematics Education (PRIME). Before that he worked as a teacher at the University of Antwerp. In his free time, Tom mostly works on his Lego Ninjago collection and occasionally plays Dungeons and Dragons.

Comments are closed.