Sprinter Sebastiaan Bowier haalde donderdagnacht in de woestijn van Nevada (VS) op de Velox ligfiets van het Human Power Team de ongelofelijke snelheid van 129,61 km/u. Helaas ligt het wereldrecord net iets hoger (133,27 km/u).

Wel was de snelheid van Bowier genoeg voor het verbreken van het Europese record, het Nederlandse record (117 km/uur), het studentenrecord en ongetwijfeld ook zijn persoonlijke record.

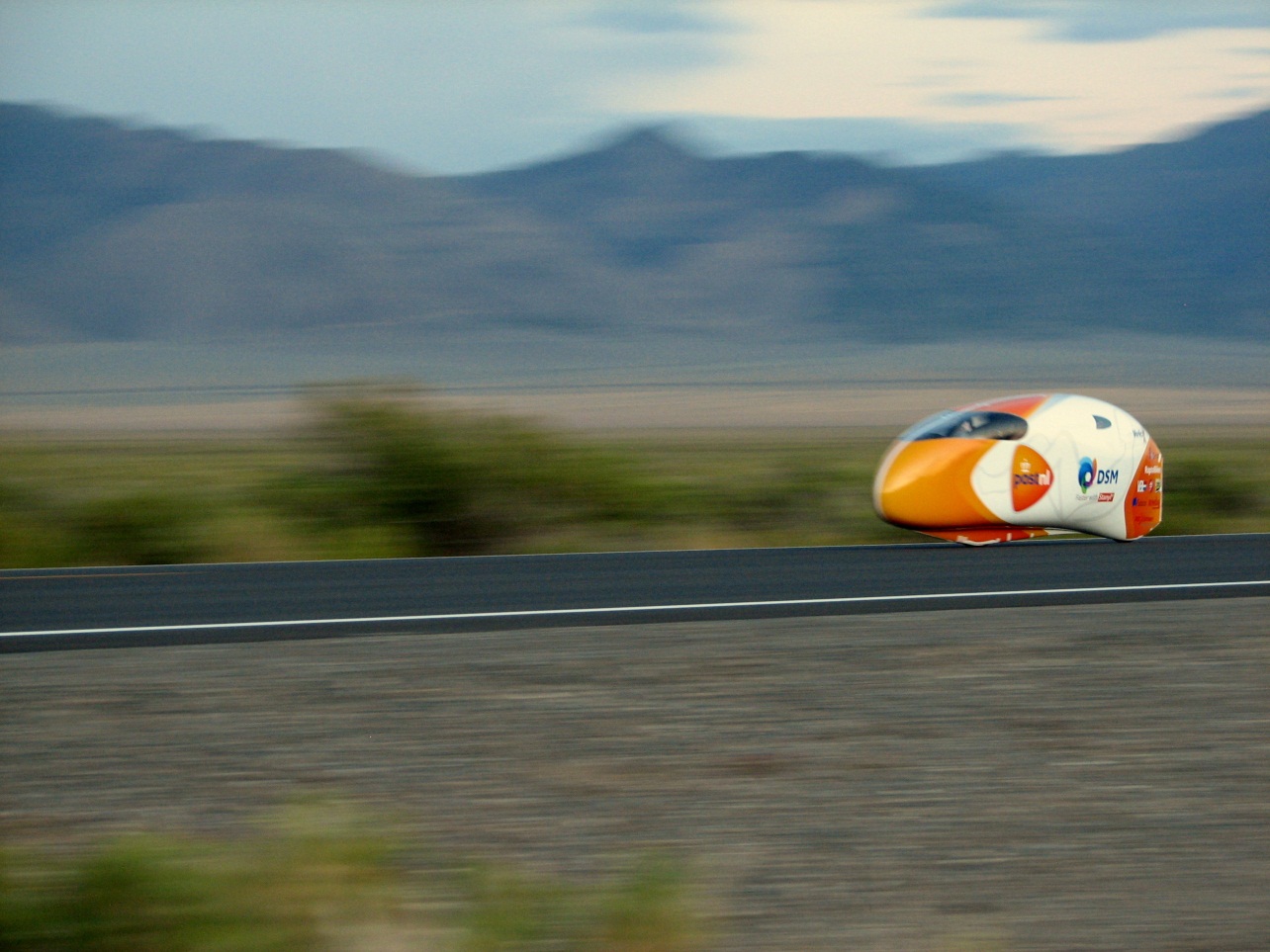

De snelheid werd officieel geklokt op een meettraject van 200 m, na een aanloop van 8 km over een kaarsrechte weg in de woestijn van Nevada (VS). Teamleider en student Werktuigbouw Hajo Pereboom: “Het is op zich al mooi om zoveel technologische disciplines, kennis en sportprestaties bij elkaar te mogen brengen, Velox te kunnen bouwen en ermee te mogen racen. Als je er dan records mee rijdt voelt dat fantastisch”.

Sebastiaan Bowier klokte ook de snelste tijd tot nu toe van de 15 aanwezige teams bij de recordweek. Hij bleef deze week Sam Whittingham voor, de heersend wereldrecordhouder, en bleef slecht 3,66 km/u verwijderd van het wereldrecord (133,27 km/u) van de Canadese oud-profwielrenner.

Verreweg de belangrijkste succesfactor is de aerodynamica van Velox. De Delftse studenten ontwikkelen de fiets volledig zelf, met behulp van windtunnels, computersimulaties en testopstellingen. De selectie van de beste fietser en de optimale racevoorbereiding en –strategie was in handen van studenten Bewegingswetenschappen van de Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam.

Het Delftse team koos voor een liggende houding en een kap die extreem weinig luchtweerstand heeft. “Vergeleken met een normale fietser, heeft ons ontwerp maar één tiende van de weerstand. Daarnaast weegt het geheel slechts 20 kg, vergelijkbaar met een stadsfiets. De ketting moet enorme krachten verwerken en daarbij minimale weerstand geven. DSM heeft speciaal voor ons een fietsketting ontwikkeld”, aldus Pereboom.

Sebastiaan Bowier, een ervaren ligfietser, werd samen met collega Gert-Jan Weijers geselecteerd uit een twintigtal kandidaten na een uitgebreide test bij de VU in Amsterdam. In juli had ligfieter Pieter Hollebrandse in de Velox op een kombaan in Duitsland het Nederlandse uurrecord al aangescherpt tot 88,3 km.

Volg de site van het Human Power Team Delft

Lees ook: World’s fastest bike (Delta, 17 maart 2011)

Delft outlook, June 2008

Hundreds of amateur radio enthusiasts all over the world have already been in contact with the satellite Delfi C3, helping TU Delft to collect data.

The milk carton-sized satellite, Delfi C3, designed and built by students and launched from India on 28 April 2008, should have had a little brother to circle around the world with by now.

More than two years ago, Delfi C3 project supervisor, Rob Hamann, of the faculty of Aerospace Engineering, told Delft Outlook that his team would launch Delfi-n3Xt by the year 2010.

“Our ambitions were a bit to high,” says the present team leader, Jasper Bouwmeester. “And for a while we had a plunge in the number of students working on the project.”

Currently, ten students from the faculties of Aerospace Engineering and Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science are working on the satellite for their graduation projects.

Bouwmeester expects that the satellite will be launched by an Indian or Russian space organization at the start of 2012: “We’re now looking into the contracts.”

Delfi C3 carried two ‘payloads’: solar cells and a solar angle meter. The satellite transmitted readings of the solar cells’ performance, and of the power the cells supplied at different angles of incidence to sunlight.

Delfi-n3Xt will be more complex, due to its micro propulsion engine, among other factors. “We will put a micro propulsion system in the satellite to demonstrate that formation flight is possible with nano satellites,” Bouwmeester explains.

“Eventually my department of space system engineering wants to develop satellite arrays which can be used for radio astronomy. For this purpose formation flight is necessary.”

The researchers will also test silicon solar cells and a more advanced radio transceiver. Yet initially they had plans for two other experiments: one involving a particle spectrometer, and one involving the satellite’s flash memory.

“Unfortunately the solar cells do not produce enough energy to perform these experiments,” says Bouwmeester. He initially thought that the satellite we would receive 20 watt, owing to a new device that steers the solar panels towards the sun, but that estimate was too optimistic. The satellite must function with 6 watt, which, nevertheless, is still much more than the 2.4 watt of Delfi C3.

The next-generation satellite should be finished next summer. The remaining time until the launch will be used to test all onboard devices.

In the meantime, Delfi C3 is still in orbit and still being tracked by the hundreds of indefatigable radio amateurs who helped TU Delft collect data in 2008. “They just continue on following the satellite,” Bouwmeester says, grinning.

Comments are closed.