PhD candidate Shou-En Zhu developed a method that could produce high-quality graphene for a fraction of the current price. What’s more, he demonstrated the quality in working devices.

After the 2010 Nobel Prize for physics was awarded to its discoverers Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, expectations for graphene were high. The properties of this single sheet of carbon atoms were expected to be exceptional: strong, transparent, electronically and thermally conducting and chemical inert. Numerous potential applications were proposed including smartphone screens, solar cells, fuel cell membranes, devices for drug delivery and even condoms.

Yet the divide between the number of hopeful scientific publications on promising applications and the actual production of large pieces of high-quality, single-crystal graphene grew into an abyss. The trough of disillusionment followed the peak of inflated expectations.

‘Although enormous amount of efforts have been devoted to graphene research, there is still a large gap between academia and industry, and how to cross the valley of death from research to business is still an open question’, wrote Zhu in his PhD thesis. He refers to the ten year European research programme European Graphene Flagship worth one billion euros.

Geim and Novoselov produced their graphene with pencil markings and scotch tape. By repeatedly sticking fresh bits of tape against a pencil mark, the graphite layer became thinner and thinner until a single sheet of carbon remained. This was called the exfoliation method. It seems an endearingly simple way to obtain a Nobel, but not a very efficient way of production. And although a dozen of other methods exist, exfoliation is still regarded as the way to produce graphene with the lowest number of defects and highest electron mobility. But the costs are enormous: a flake the size of a hair made in this way costs more than €1,000 – making graphene one of the most expensive materials on earth, according to Nature.

Synthetic graphene

Synthetic grapheneSynthetic graphene

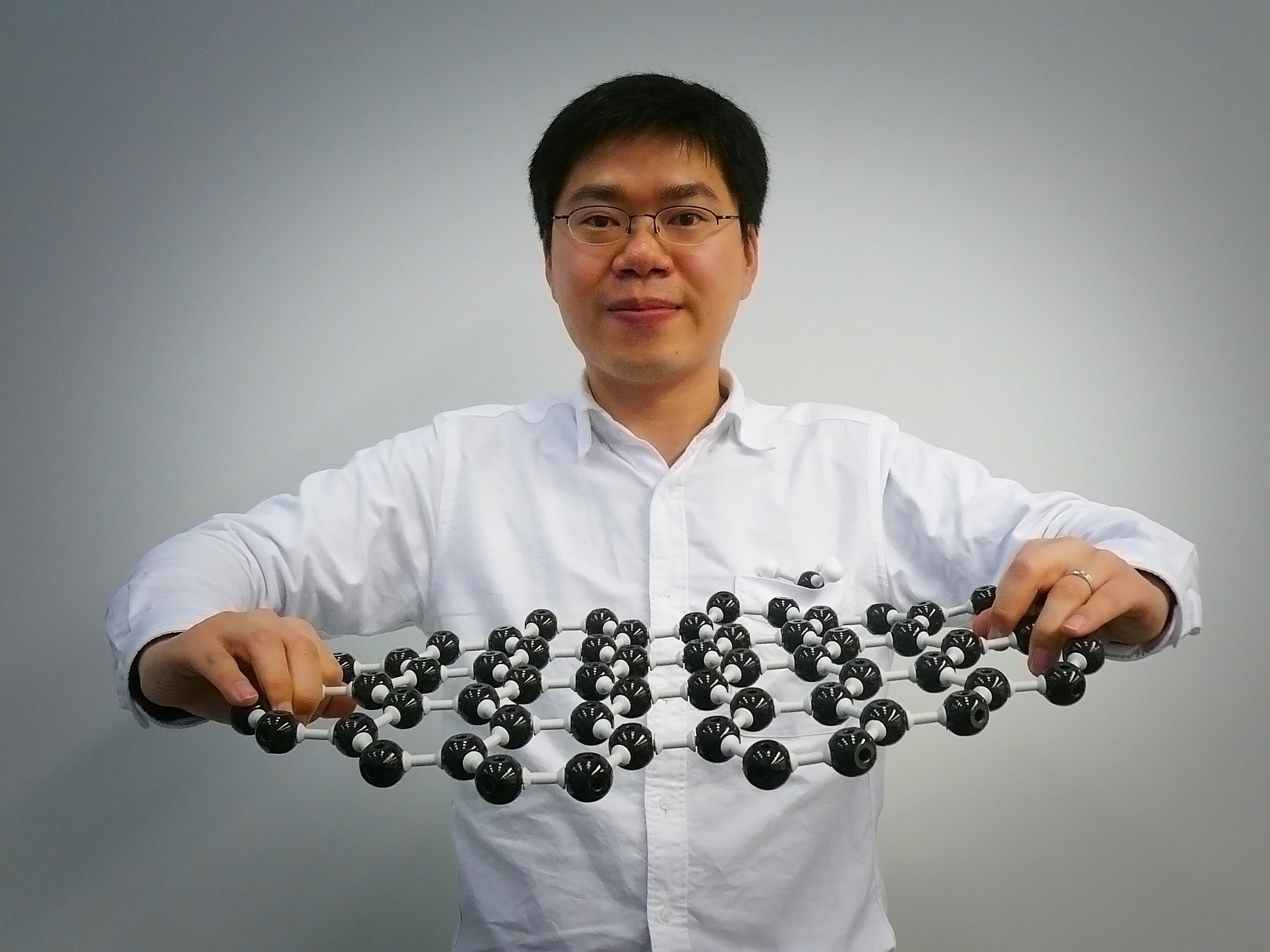

Yet, all you need to produce graphene, natural gas and copper, is available in most kitchens, said Zhu. What’s more, he has demonstrated millimeter-sized graphene crystals made by chemical vapour deposition of methane on a copper sheet. He leads of low-pressure mix of hydrogen, methane and argon over a copper sheet at a temperature of 1,000 degree celsius. The copper acts as a catalyst in stripping the hydrogen from the methane, leaving pure carbon that sticks to the surface and perfectly aligns with other carbon atoms into this endless sheet of pure graphene.

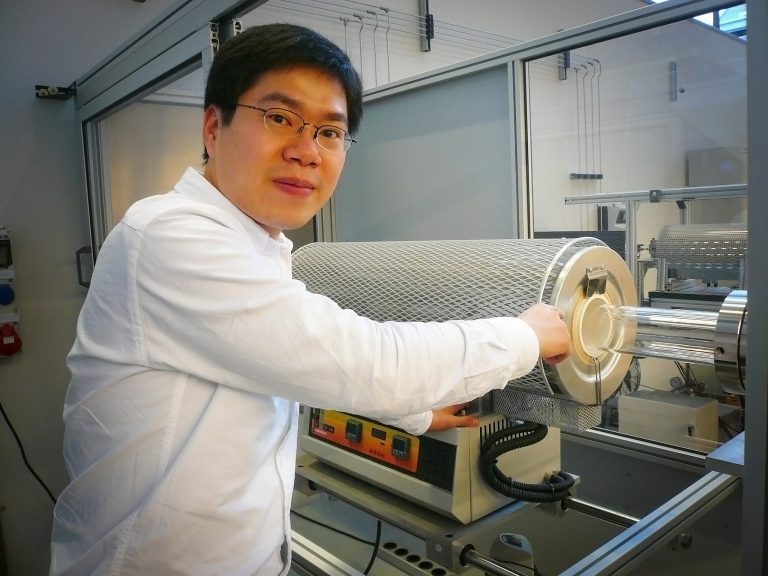

Other parties need ten hours to produce graphene by deposition. Zhu, however, has brought back the production time to about one hour by splitting the quartz tube in which the deposition takes place from the oven that surrounds it. After deposition, he simply slides the furnace away to speed up cooling.

“Now a single piece of graphene costs about €1,000”, said Zhu. “We expect to reduce the price by a factor of thousand to about €1 per piece in a few years.”

But is it just as good? Zhu demonstrated that millimeter-sized piece of graphene was, in fact, one single crystal by freely moving the electrons around in it. Together with his colleagues, he applied a perpendicular magnetic field to the graphene. The field pushed the free moving electrons into circular trajectories without any scattering. Thus he proved that the synthetic graphene was flawless.

Another demonstration is the pressure sensor Zhu made and which he published in Applied Physics Letters in 2013. It consists of a silicon nitride diaphragm with a 0.3 mm hole in a silicon support. The diaphragm is covered with graphene. The membrane stretches with the pressure difference over it, which changes the electrical resistance. The device works as a pressure sensor with a sensitivity of 8.5 mV/bar.

Zhu, who won the 2011 Young Wild Idea Prize,is profiling himself as Mr. Graphene ever more strongly. He’ll defend his PhD thesis on the March 3, 2015. As for his further goals, he says: “I want to make graphene real and bring it into daily life. Bring it into products anyone can touch.”

-Shou-En Zhu, ‘Chemical vapour deposition of graphene, a route to device integration’, PhD supervisor Prof. Guido Janssen, section of micro & nano engineering at 3mE Faculty.

Comments are closed.